Before you toss every packaged food into the trash, consider that the line between“healthy” and “ultra-processed” is blurrier than wellness gurus would like you to believe. A fortified wholegrain loaf can be branded a dietary villain, while bacon and puffed rice sail through unscathed. The real story isn’t about purity versus poison; it’s about convenience, nutrition, and whether we’re confusing classification with common sense.

Ultra-processed food, or UPF, has become the wellness world’s favorite villain. Celebrity doctors and health influencers have built whole careers out of blaming it for our ills. A recent American Heart Association report in Circulation reveals that Americans get 55% of daily calories from UPFs (62% for youth, 53% for adults), highlighting our reliance on these foods.

But while there’s some fascinating research around this topic, I think we’re in danger of losing our common sense around the issue of processed foods.

The research and publicity around UPF have served to highlight our reliance on, often low-nutritional-value, prepackaged foods, and their potential health effects. But it’s a hard no from me when UPF evangelists insist I can’t use a bottle of tomato pasta sauce or must choose a super-expensive three-ingredient sourdough for family meals over an inexpensive wholemeal sliced loaf.

Categorization Is Inexact and a Little Arbitrary

The main issue is with the NOVA classification system, by which most UPFs are categorized (there are other systems, too, which only add to the confusion). The NOVA system was developed by researchers at the Center for Epidemiological Studies in Health and Nutrition at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, and has been widely adopted in studies and dietary guidelines. However, it reveals some unusual anomalies.

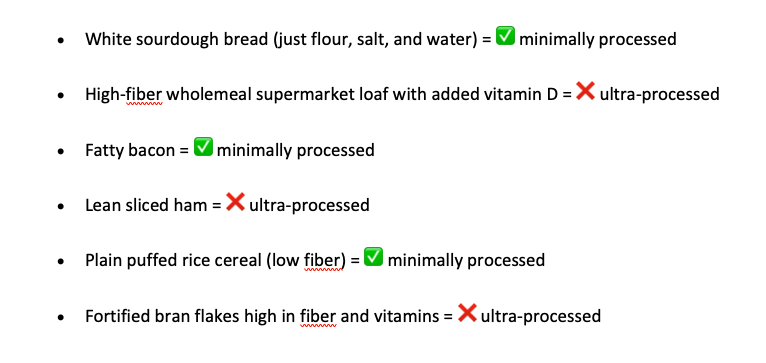

The problem is that the UPF categories — unprocessed, culinary, processed, and ultra-processed foods — encompass a vast and diverse range of foods, from ice cream and fizzy drinks to wholegrain bread and fortified soy milk. Some UPFs, though nutritionally beneficial, are penalized by the classification because of how they’re made (e.g., using industrial methods).

In these cases, the more nutritious option is often classed as ultra-processed simply because of added ingredients like emulsifiers, fiber extracts, or vitamins — not because it’s inherently unhealthy.

Other nutritious foods you’d lose on a low-UPF diet include baked beans, fruit yogurts, bottled tomato pasta sauces, and plant milks like almond, soya, or oat milk — all obviously healthier than candy, cakes, and fizzy drinks.

What the Research Shows

Observational research has suggested that a high ultra-processed food diet may be linked with increased risks of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, dementia, and depression, as shown in studies in the BMJ, British Journal of Nutrition, Frontiers in Nutrition, and Nutrition Journal.

The AHA report says high UPF intake, especially products like sugary drinks, raises cardiometabolic risks by 25–58% and mortality by 21–66%. But it agrees that some UPFs, like wholegrain breads, can be nutrient-dense and beneficial, supporting the view that not all UPFs are villains.

Some of the most interesting and well-controlled research focuses on weight control.

In a pioneering study at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Kevin Hall and his team directly compared ultra-processed diets with unprocessed/minimally processed diets under tightly controlled conditions. Twenty inpatient adults ate as much as they wanted from meals matched for calories, macronutrients, fiber, sodium, and energy density. Both diets were designed to be equally tasty; however, despite these controls, participants consumed approximately 500 more calories per day on the ultra-processed diet and gained weight, whereas they lost weight on the unprocessed diet.

A more recent and comprehensive study published in Nature Medicine tested two diets over 8 weeks each:

Ultra-processed diet: 90.7% of calories from UPF

Minimally processed diet: 82.1% of calories from MPF

Participants again ate as they wished, with both diets aligned to UK dietary guidelines. Both groups lost weight, but those on the ultra-processed diet consumed more calories and lost weight more slowly.

Interestingly, there were more dropouts in the minimally processed diet group, despite the meals being designed to be similarly tasty and delivered fully prepared to participants. This rate would likely increase further if participants had to cook these meals themselves over an extended period. The finding underscores the critical role of convenience in real-world eating habits and highlights the need to make healthier, nutritionally balanced UPFs more accessible.

My Bottom Line, UPFs Are a Diversion

UPFs don’t magically cause weight gain — it’s that people involuntarily eat more, likely due to:

Greater energy density: More calories packed into a smaller volume

Texture: Softer, easier-to-eat foods encourage faster consumption

Palatability and ease: UPFs, particularly those high in sugar and fat, tend to be very appealing and easy to prepare

Emulsifiers, artificial sweeteners, and other additives have been suggested as potential reasons why UPFs might lead to overeating or metabolic harm. However, current evidence is inconclusive about whether typical consumption levels of these ingredients are directly harmful.

My feeling? Focusing on overall diet quality, guided by established healthy eating recommendations, is just as effective—and more practical—than targeting UPFs alone. Indeed, the Nature Medicine study suggests that a diet meeting current guidelines isn’t detrimental to weight maintenance, regardless of the processing level.

Cooking everything from scratch using minimally processed ingredients is a huge pressure. I’d rather see policy efforts focused on encouraging manufacturers to produce healthier UPF options, such as better ready meals, rather than sending people back to the kitchen.

UPF foods can be part of a balanced diet, even helping with weight loss, as long as nutritional targets are met.

Practical Tips

No need to obsess over every label. However, when choosing between two similar products, it makes sense to scan the ingredients list and opt for fewer additives.

Choose crunchy, chewy, or harder-to-eat foods that slow down your eating pace.

When buying ready meals, add vegetables or salad.

Calories still matter — a 1,000-calorie home-cooked meal will likely lead to more weight gain than a 500-calorie ready meal.

Swap highly processed snacks, such as cookies and savoury snacks,for less processed and more nutritious options, like nuts and fruit.