“What do you do when you live in a country where your government is doing terrible things?” the filmmaker Julia Loktev recently asked me. In the case of Mark Mothersbaugh and Gerald Casale, the answer was: Start a band.

If all you know of Devo is hit singles like “Whip It,” they don’t sound like a band that was formed in response to the Kent State shootings of May 4, 1970, when National Guard troops opened fire on an anti-war protest and killed four unarmed college students. With their clipped guitars and squiggly synthesizers, their songs don’t sound like protest music, and their lyrics are a jumble of absurdist poetry and references to midnight movies and discarded junk culture. Compared to the straightforwardness of Neil Young’s “Four dead in Ohio,” a line like “God made man, but he used the monkey to do it” doesn’t point fingers in any obvious direction, except perhaps at humanity itself. But while Young was writing from a safe distance, Casale, then an art major, witnessed the Kent State killings up close, and knew two of the victims personally. And to him and his fellow students, Mothersbaugh and Bob Lewis, the appropriate response wasn’t a melancholy lament but an attack as violently senseless as the shootings themselves, channeled through art instead of a rifle barrel.

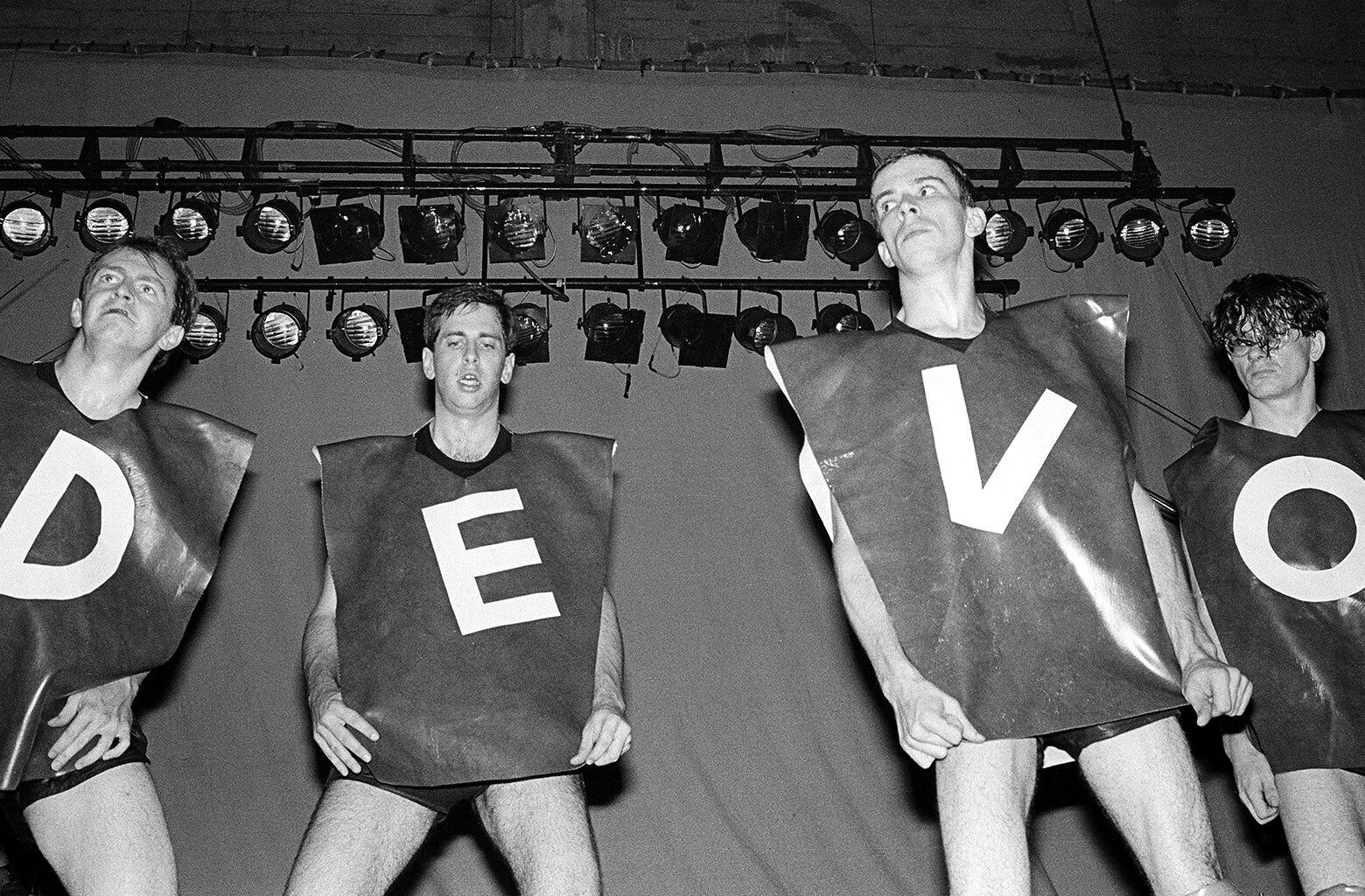

Chris Smith’s documentary Devo, which has finally gotten a release on Netflix more than a year and a half after it debuted at Sundance, is a delightful journey through the back catalog of one of the most playful and quick-witted bands in rock history. But its most important aspect is the way it restores the conceptual underpinnings of Devo’s music that half a century of radio play and contextless streaming has stripped away. As Mothersbaugh points out in the documentary, Devo was an idea long before it was a group, and it was years before the members even thought of making music their focus.

That idea was “de-evolution,” taken from an apocalyptic 1925 pamphlet that also gave its name to the early song “Jocko Homo.” Although American exceptionalism was at its peak, bolstered by the nation’s victory in the space race, Casale and Mothersbaugh saw humanity, themselves included, reverting back to its most primitive form, and they decided to make music that catered to those instincts, with mechanical beats, singsong melodies, and strangled vocals that sounded like the singer was still going through puberty. But while punk bands adopted primitivism as a way of life, Devo did it with an arched eyebrow, donning rubber masks that made them look like monstrous babies rather than simply acting like kids. “One thing we learned” from Kent State, Mothersbaugh remembers thinking, was that “rebellion is obsolete.”

Lewis left Devo after a little while, and Mothersbaugh and Casale’s brothers, both named Bob, joined in his stead. (Guys named Bob are to Devo what drummers are to Spinal Tap.) Early songs were designed to drive what little audiences showed up to their gigs out the door, but an encounter with the Ramones taught Devo that they could speed up their dirgelike tunes without sacrificing any of their impact. Picking up the pace weirdly made them both poppy and danceable, art rock that teased the mind and hit the body’s pleasure centers, too. As Casale once told me, “We were like Kraftwerk with pelvises.”

Although Smith’s documentary barely runs more than an hour and a half, he finds room to address some of the band’s more larkish diversions, like the period when, as a goof on the rise of American televangelism, they opened their shows as a Christian group called Dove, the Band of Love, a ruse of which their angry audiences were apparently unaware. (Maybe they just wanted to get booed off the stage for old times’ sake.) Sadly there’s no room for Dev2.0, the bizarre early-21st-century project in which a group of Disney tweens recorded bowdlerized versions of Devo songs, but it’s about as comprehensive as a brief history of a band’s 50-year career can be.

The Man Behind the Most Infamous Moment in Any Series Finale in Ages Explains How He Did It

One of Rock’s Greatest Bands Started as Satire. Then It Became Everything It Satirized.

Netflix’s Most Popular Movie in Years Has Now Birthed a No. 1 Song

A24’s Latest Has Already Made More Money Than Any Star Wars Movie. I Bet You’ve Never Heard Of It.

There’s an irony the documentary never quite gets around to addressing, though, which is that as Devo got bigger and bigger, their ideas got drowned out by their own success. Smith devotes a section of the documentary to the confusion caused by the unexpected breakout of “Whip It,” which was released as a single after the label’s first choice, “Girl U Want,” utterly flopped. Some fretted the lyrics were about masturbation or sadomasochism—what, exactly, was the “it” meant to be whipped?—and the band amplified that idea with a music video that played like a PG-rated stag film. But the video came to define the song, especially once MTV launched in 1981 and put Devo, as one of few bands with a substantial catalog of ready-made visual content, into heavy rotation. The joke became reality, which proved the band’s point about cultural decline, but only by turning them into an example of the phenomenon they meant to undermine. (Although MTV no longer plays music videos, Mothersbaugh still makes about $1 million a year from “Uncontrollable Urge,” the theme song to the channel’s perennial slot-filler Ridiculousness.)

Sam Adams

A Gripping New Movie Has a Terrifying—and Inspiring—Message About the Fight for America Ahead

Read More

With only one new album released in the past 35 years, it’s pretty clear Devo’s days as hitmakers are behind them. Mothersbaugh writes music for TV and movies (most notably for several Wes Anderson films) and Casale has worked as a commercial director, which is de-evolution at its finest. Perhaps it was inevitable that a band that started out warning us that humanity was moving backward would itself evolve into a nostalgia act. But this turns Devo into a cautionary tale as well as a catalog of past triumphs, a reminder that the band’s most acutely damning lyric—“Freedom of choice is what you got, freedom from choice is what you want”—applies to them as well.

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.