Where Love and Imagination Colour the Dark: Essays on Thomas Kinsella

Author: Edited by Adrienne Leavy

ISBN-13: 978-1943667109

Publisher: Wake Forest University Press

Guideline Price: $29.95

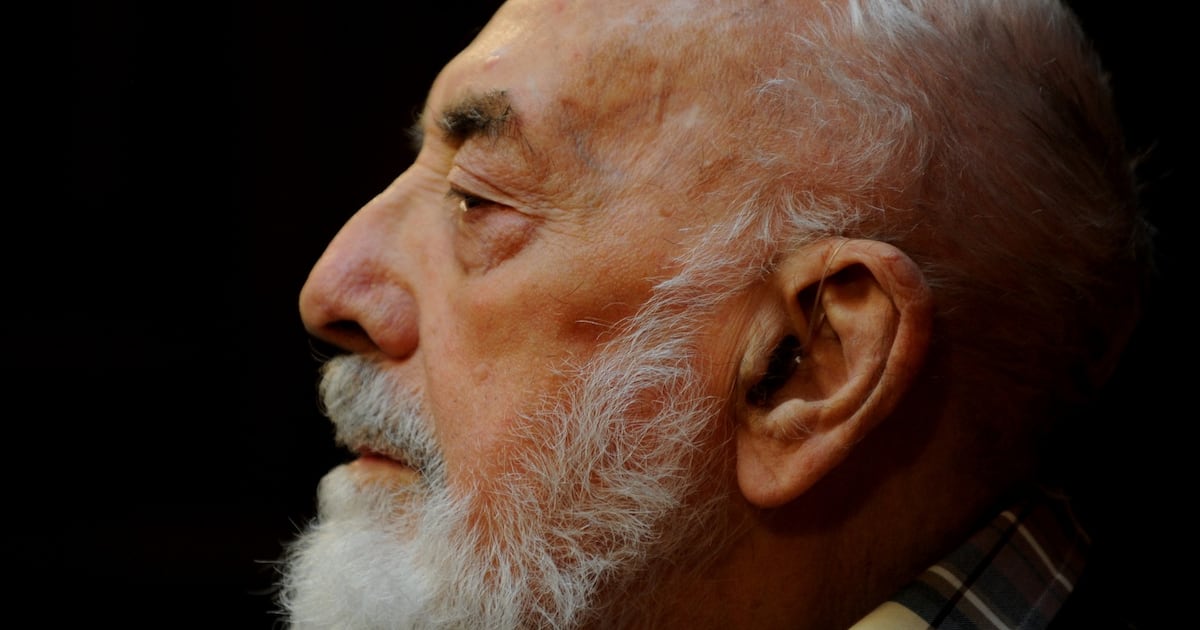

Thomas Kinsella is without doubt, after James Joyce, the most important literary artist to emerge from Catholic Ireland. His work is one of our small culture’s crowning achievements, and the scholar Adrienne Leavy has assembled in this collection of essays a group of the most brilliant Irish poets and scholars to prove the point.

Kinsella’s work is illuminated by the remembered cobblestones and lanes of inner-city Dublin, so brilliantly outlined here in essays by Gerard Smyth, the late Gerald Dawe and Hugh Haughton. This Dublin ambience gives his work a Swiftian permanence and a feeling that his poems will endure as long as the cobblestones of Dublin endure.

Yet his mind was as disturbed and fractured as Wood Quay, and the entire quest of his poetic career was a search for order and relocation in the dreadful postwar disturbances of human consciousness. His was a Jungian quest with a Catholic-woven suit of armour, as Leavy shrewdly emphasises: “Aside from Yeats’s aesthetic interest in occultism and spiritualism, Kinsella’s creative interest in dreams and psychoanalysis has no other counterpart in modern Irish poetry.”

Kinsella’s career began in a distinguished if conventional manner. While climbing the Civil Service ladder to real seniority he produced two of the most brilliantly assertive and classical poetry collections of the modern era: Another September (1958) and Downstream (1962). The sheer energy of this time in Kinsella’s life is superbly explained in what I think is one of the finest literary essays ever written, Andrew Fitzsimons’s The Moment of the Poem: Kinsella’s Baggot Street Deserta and Beyond.

By mapping and analysing the world outlined in Seán J White’s journal Irish Writing of Spring, 1956, where the poem first appeared as Unfinished Business, Fitzsimons uncannily sets up a description of the intellectual climate around Kinsella’s activity. “The moment of the poem is an interregnum in the Gramscian sense,” he observes. Here are Kinsella’s words: “In a wrist with poet’s cramp, a tight/ Beat tapping out endless calls/ Into the dark, as the alien/ Garrison in my blood/ keeps constant contact with the main/ Mystery, not to be understood.” This essay is the very embodiment of the Kinsella aesthetic and mental weather.

Dublin remained the locus of Kinsella’s thinking, and Hugh Haughton provides us here with an inspired reading of Kinsella’s A Dublin Documentary. Gerard Smyth, also, deepens our understanding of that Dublin dinnseanchas, recalling his first encounter with a Kinsella book in a Dublin 8 Public Library “where the poet himself had been a book borrower in his youth”. Smyth’s early reading of Dick King had an immediate effect, triggering “a moment of liberation in my understanding of what a poem can be and can achieve, and into what territory it can fruitfully venture”.

Because of such assiduous reading, Kinsella’s own imaginative journey from 38 Phoenix Street to the route of The Táin, Cooley, Co Louth, was primarily the deepening of an inward journey. The landscape, place and placenames of that great poem are very successfully covered here by the archaeologist Paul Gosling in his essay Story and Place in Thomas Kinsella’s Poem The Route of the Táin.

Gosling’s reference point is the retrospective poem of 1973 about a journey into the mythical landscape that Kinsella took in 1969. Kinsella had imaginatively walked this landscape many times. Thomas Dillon Redshaw’s masterful essay, Making the Great Táin, 1951-1970: Thomas Kinsella, Liam Miller and Louis le Brocquy, reminds us, also “that Kinsella’s translation, le Brocquy’s brush drawings, and Miller’s design of the book went immediately to the very centre of Irish literary, artistic and cultural life in Ireland in the early 1970s”.

Derval Tubridy’s essay here deepens our knowledge of this synthesis. In Imaginative Reality: Thomas Kinsella and Visual Art, she explores designs from Kinsella’s earliest publications as well as The Táin and the later Peppercanister Series and explains the astonishing range of the artwork that “both frames and contextualises Kinsella’s verse”.

In the final essay of the book, a tour-de-force, editor Leavy deals with the enduring love of Kinsella’s life, the complex Eleanor Walsh who was a radiology student at UCD when the poet met her in 1951. Eleanor drew the poet into that “difficult, scrupulous art” of love poetry, becoming the subject of his greatest works, from A Lady of Quality to Love Joy Peace in 2011.

Leavy recalls Eleanor’s near-fatal illness from TB as well as the later myasthenia gravis, and yet her powerful recovery leading to their long marriage of love and mutual support. They were part of a Dublin generation born for the long haul. Leavy, here, has captured Eleanor’s presence in the work and her great influence on the poet’s work and outlook.

This is a powerful set of essays, and its publication is a timely salute from afar by Kinsella’s long-time American publisher, Wake Forest.

Thomas McCarthy’s latest collection of poems is Plenitude (Carcanet) and his collected essays, Questioning Ireland, were recently published by The Gallery Press