Hand-woven and dyed fabrics, elaborate gold and beaded jewelry, women with hennaed hands and feet, and military men in suits fill the work of photographer Seydou Keïta (1921–2001), the subject of a new exhibition, “Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens,” at New York’s Brooklyn Museum.

For the show—the largest North American survey of Keïta’s imagery to date—guest curator Catherine E. McKinley has brought together nearly 300 photographs, some never before seen, as well as personal belongings of Keïta’s, including vintage cameras. Born in Bamako, Mali, during French colonial rule, Keïta developed his studio practice against a backdrop of political unrest. For a time, French law forbade photography by Africans, but Keïta persisted, gaining popularity as Bamako’s most sought-after photographer. For more than a quarter century, Keïta photographed Bamakois from all walks of life—government officials, intellectuals, artists, and everyday members of Mali’s rising middle class.

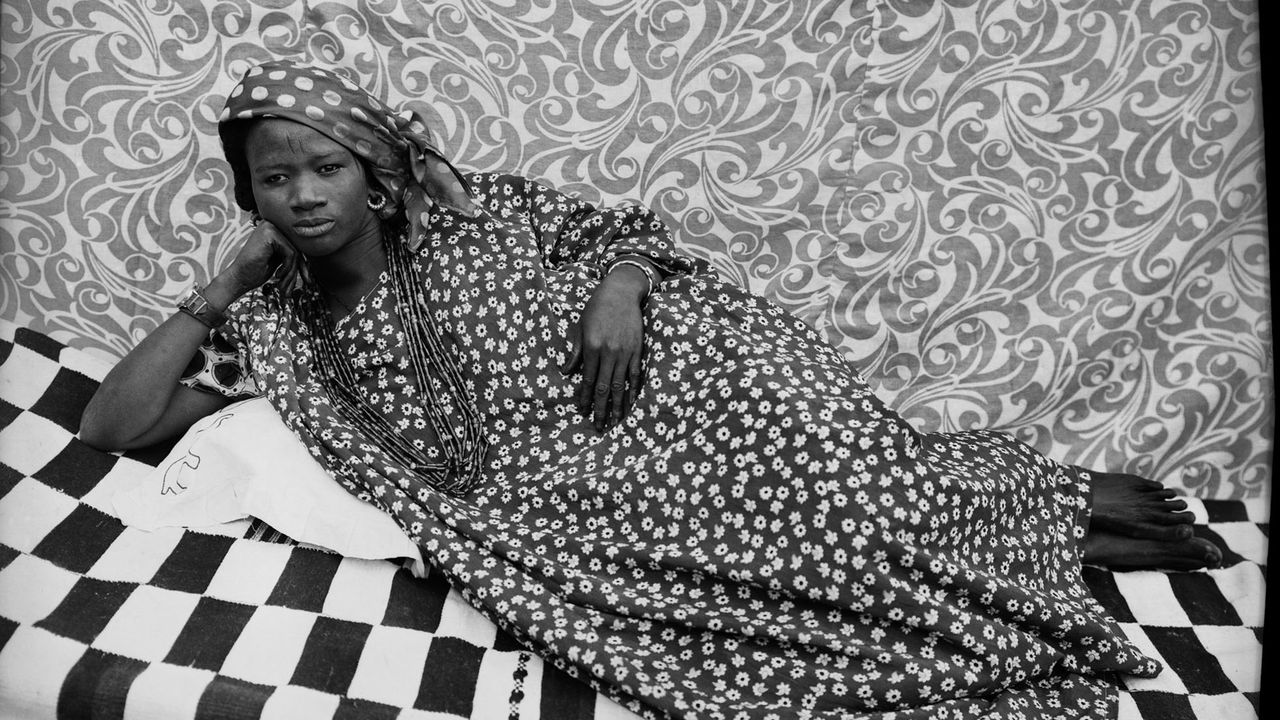

Seydou Keita. Untitled, 1959, printed ca. 1994-2001. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection.

© SKPEAC/Seydou Keita, courtesy The Jean Pigozzi ‘Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, NY

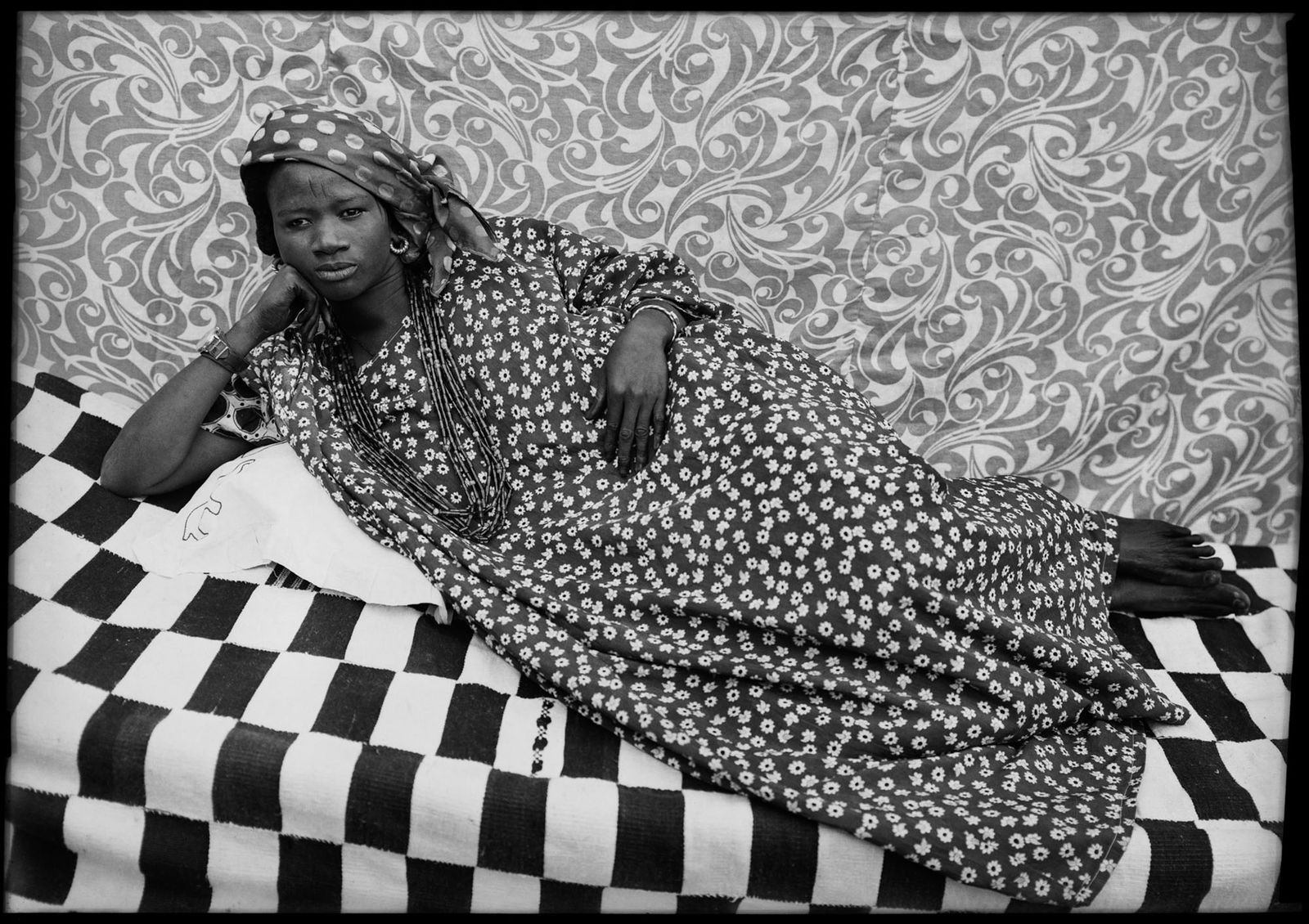

Seydou Keita. Untitled, 1949-51, printed 1995. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection.

© SKPEAC/Seydou Keita, courtesy The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, NY

Vogue sat down with McKinley to discuss the timeliness of the show, what makes Keïta’s work so singular, and how design sits at the heart of his photographic oeuvre.

Vogue: Exhibitions like this are years in the making. How long have you been working on it and what were some of the pivotal moments that led to it?

Catherine E. McKinley: I worked on it for just under two years, but it’s life work. I’ve been studying African photography and textiles since college. I’m almost 60, so that gives you an idea. I was first introduced to Keïta in 1991, with his show at the Museum for African Art. My fascination became an immediate love. Going to Bamako was when the real work started. I met with the Keïta family and that meeting was pivotal.

Seydou Keita. Untitled, 1949-51, printed ca. 1994-2001. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the Musée national du Mali.

© SKPEAC/Seydou Keita, courtesy The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, NY

Seydou Keita. Untitled, 1953-57, printed ca. 1994-2001. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection.

© SKPEAC/Seydou Keita, courtesy The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, NY

Why Keïta and why now?

This is the most extensive North American show he’s had. The fact that it hasn’t happened in the 30 or so years since he was discovered is remarkable. It’s a chance to offer new information, a new framework. This is an important year for him and for African photography. Important shows are opening. MoMA has a large retrospective in December. African photography’s going to be on the radar in a big way.

Seydou Keita. Untitled, 1949-51, printed 1998. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection.

© SKPEAC/Seydou Keita, courtesy The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, NY

Seydou Keita. Untitled, 1957-60, printed 1994. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection.

© SKPEAC/Seydou Keita, courtesy The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, NY

What was the process of acquiring loans from private collections and working with the family?

Jean Pigozzi is the copyright holder and has most of Keïta’s works. I made an effort to find work in individual collections and institutions like the Chicago Art Institute and the Musée National du Mali. I wanted to represent collections that were unknown, whether family collections or small family-run archives on the continent. To my delight, some of the best materials were in those collections. Textiles held in families were superior to what was held in Western institutions.