“Look, what’s that?” Ed Pack was outside the Houses of Parliament when something caught his son’s eye.

Even for a summer’s day in Westminster, it was busier and noisier than usual because thousands of people with placards were protesting against Boris Johnson’s decision to suspend parliament in the run-up to Brexit. On the way back to Victoria Station, however, Pack and his son looked up just long enough to notice a strange dark speck in the sky.

“We knew it wasn’t a buzzard or a red kite,” says Pack. “It was the size of it. Not flapping, just gliding. It felt out of the ordinary.”

The next day, scrolling through social media, the retired architect saw a post asking if anyone had seen a white-tailed eagle over Westminster the previous day. “I nearly fell out of bed,” he recalls. It turns out that’s exactly what he saw: Britain’s biggest bird of prey.

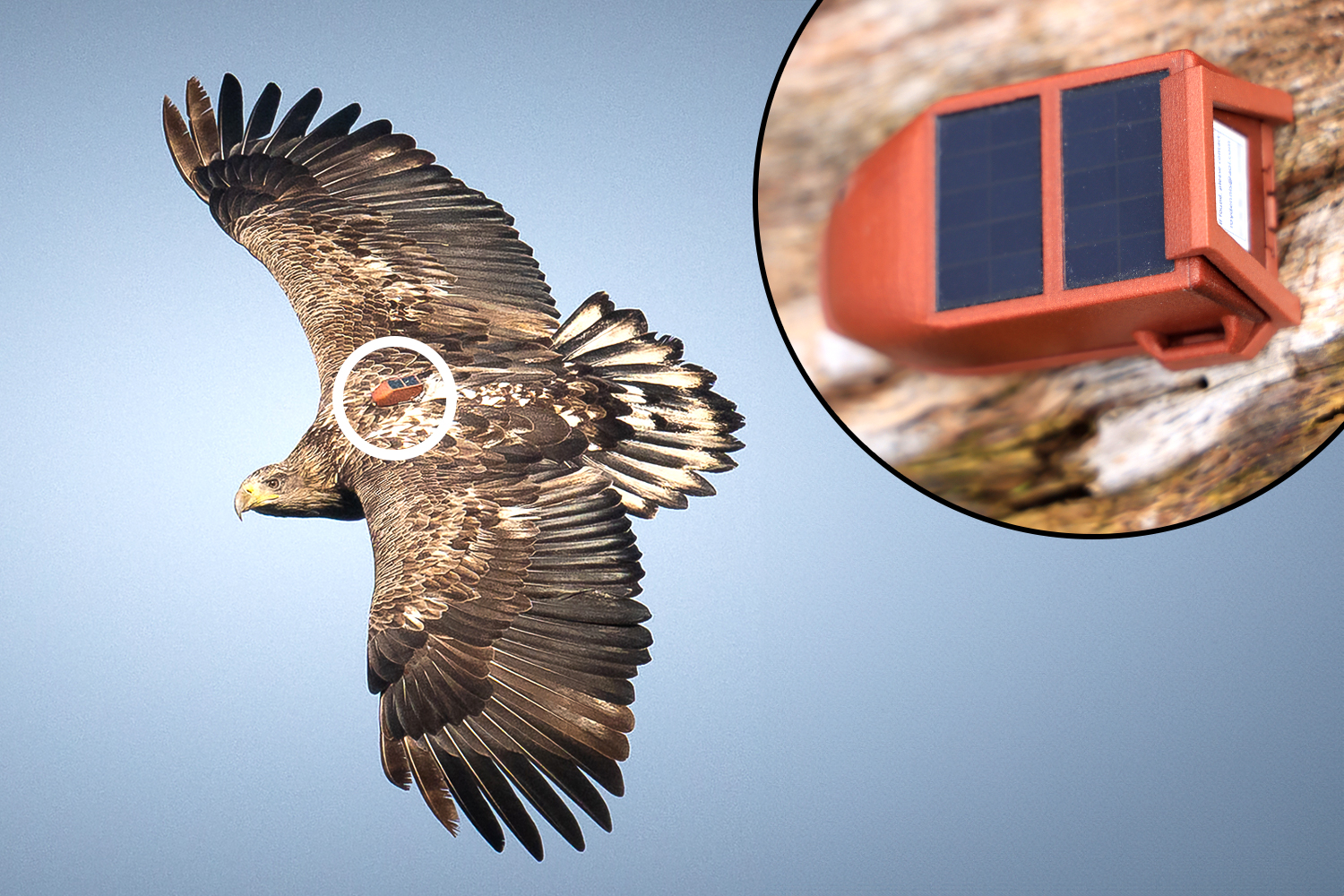

And it wasn’t just any white-tailed eagle; it was Culver, the first sea eagle to fly over southern England in 240 years. The satellite tag on his back showed that for his first big exploratory flight the young eagle had gone straight for the capital, flying directly over the Houses of Parliament, along the South Bank and over Blackfriars Bridge before continuing along the Thames then looping back down to his new home on the Isle of Wight.

At 2.21pm that day, August 31, 2019, he was only 416 metres above Victoria Station. The circled speck below shows how Culver appeared to Pack (you’ll have to look closely):

This is the route he took that day:

The timestamp on the photo matched the satellite data, confirming that Pack and his son, George, had spotted Culver on that first fabulous flight.

“To have this primeval presence overhead in contrast to the crowds below … It felt like the medieval meeting the modern world,” says Pack, 66, from East Sussex. “We felt quite blessed to have seen it.”

Soaring above, but unseen

Six years on satellite data from other white-tailed eagles that have since been reintroduced to England have revealed surprising journeys through urban skies. They are flying over our motorways, shopping centres and train stations all the time. We simply don’t notice.

If you were shopping in the Bullring shopping centre, Birmingham, on October 2 last year, and looked up at about 10.21am, you might have seen a young female sea eagle returning to the south coast of England after spending the summer in the Scottish Highlands.

Or perhaps you were stuck in traffic on the M25 on September 11 last year. How many motorists realised that the first white-tailed eagle to have fledged from an English nest in almost three centuries was 802m above the Dartford Crossing?

Anyone in Edinburgh city centre at 11.28am on May 10 last year might have caught a glimpse of the same eagle, cruising at 771m over Lothian Road and Haymarket Station and within a few hundred metres of Edinburgh Castle.

“If you had been looking out [west] from Edinburgh Castle at that time, you would definitely have been able to see it,” says Tim Mackrill, excitedly. As the man leading the satellite tracking mission, he probably knows more about the detailed whereabouts of this new generation of eagles than many people know about their own children.

Dr Tim Mackrill observing eagles on the Isle of Wight

JULIAN BENJAMIN FOR THE TIMES

The technology allows Mackrill and his colleagues at the Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation and Forestry England to plot exactly where the eagles are re-establishing themselves.

In the present age of extinction, conservation success stories can be rare, but the return of white-tailed eagles, first in Scotland, and now in England, has surpassed all hopes.

White-tailed eagle talons have been discovered in caves used by Neanderthals. By 1780, however, they had been wiped out of England and the last survivor was shot in the final stronghold of Shetland in 1918.

With a heavy-set body, chunky yellow beak and broad wings, it’s our biggest native eagle as well as the largest in Europe and the fourth largest in the world.

“For such a big bird, it’s amazing how little they are seen,” says Mackrill.

The popular image of the eagle soaring above remote crags is mostly thanks to our other native eagle, the golden eagle. Though bigger, white-tailed eagles are more at home in semi-urban environments.

“It’s a bird that lives in lowland countries,” explains Mackrill. “There’s that romantic view of an eagle in the wilderness. But they are on the outskirts of Rotterdam and in Hamburg. There’s a pair in Helsinki city centre.

“If you went to Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, it’s normal for them to be in these kind of [metropolitan] areas. We’re just catching up.”

In that respect, an eagle cruising over Canary Wharf (665m) and South Croydon (1,387m) on April 17 last year should not, perhaps, be as surprising as it sounds.

“Humans killed them,” says Mackrill. “That’s the only reason they were not here. All we’re doing is restoring them to where they would have been. Nature should not be confined to nature reserves.”

Precious cargo: the first chicks

For Roy Dennis, it has taken more than 50 years of perseverance to get to this point.

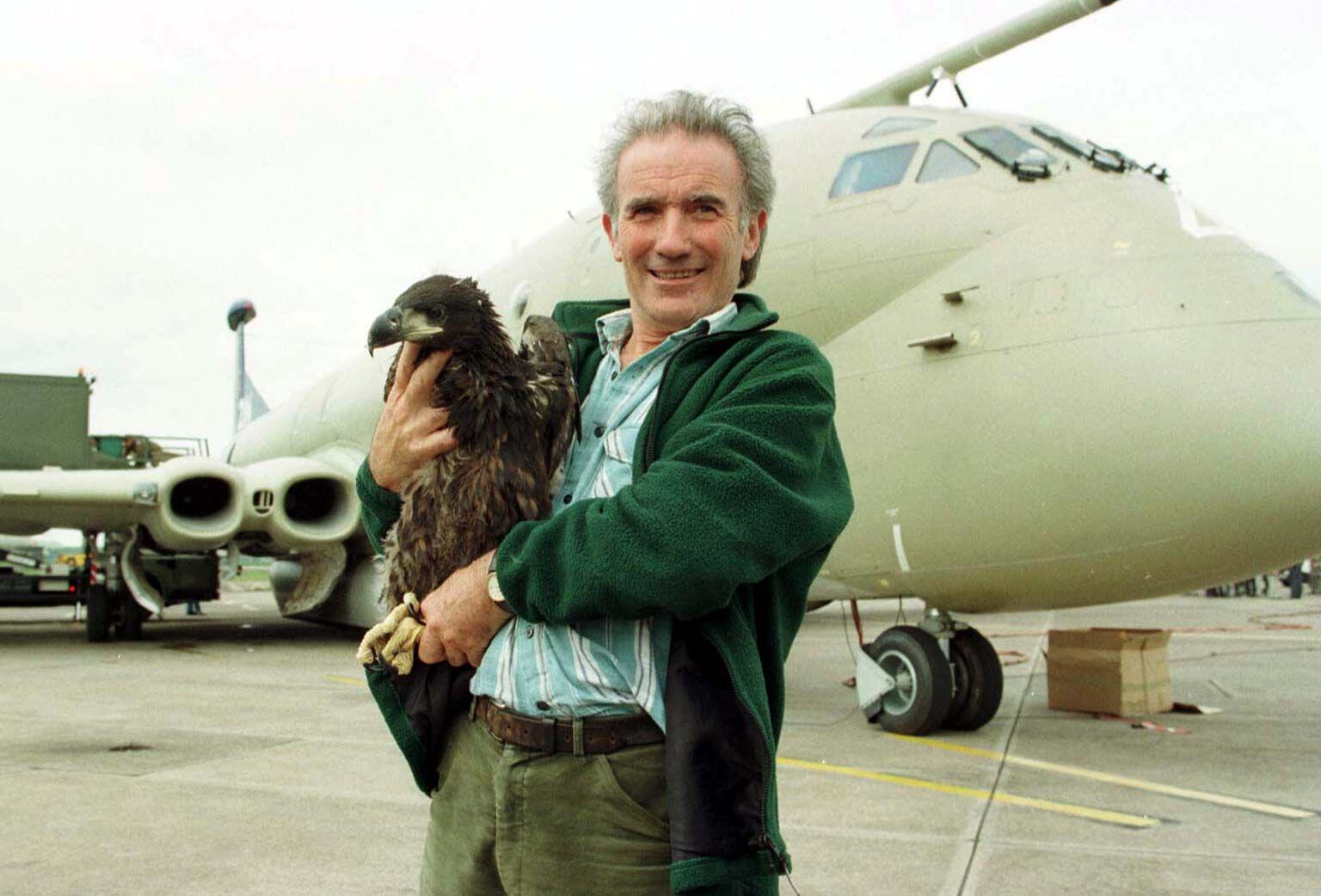

He was there, waiting on the tarmac at RAF Kinloss for the very first delivery of eaglets donated by Norway to kickstart the reintroduction in Scotland.

It was his responsibility to drive the precious cargo in his Ford Escort van to their new home on the Hebridean island of Rum.

“I remember the intense excitement of seeing the Nimrod thunder down and land, and the steps came down,” recalls Dennis, 85.

The chicks in the crates were already huge. “They were big brown lumps of feathers. They’ve got these great, big, beautiful dark eyes that just look at you.”

Roy Dennis with the eagle chick, named Nimrod after the aircraft, behind, used to transport it

GORDON GILLESPIE/ALAMY

It took ten years before the first chick successfully fledged in Scotland. Promisingly, the English project has had an even better start with six wild chicks born within the first six years. Eagles released in the Isle of Wight have gone on to establish territories in Wales, Lincolnshire, Dorset and Sussex.

There have been losses along the way. A month after his flight over Pack and the protesters at Westminster, Culver vanished. “We stopped naming them after that,” says Mackrill.

One was electrocuted. Another was hit by a train when it tried to feed on a deer carcass. Some have disappeared, their trackers suddenly malfunctioning, in suspected cases of deliberate raptor poisoning. Shooting estates prefer their grouse and pheasants to be killed by paying clients, not birds of prey.

There are about 200 breeding pairs in Scotland. Of the 25 birds released in England from 2019 to 2021, 11 are still alive, which is about the survival rate that was expected. A further 20 birds have been released over the past two years; 17 of these young eagles are still alive. They won’t start breeding until they are 4-5 years old. England can now boast its first two breeding pairs. Ireland has about ten breeding pairs.

• Frisa, Scotland’s oldest white-tailed eagle, dies aged 32

“They are wild birds,” says Mackrill. “Once they are released, there’s nothing we can do.”

Call of the wild

Once seven-week-old eaglets are transferred from Scotland to the Isle of Wight, they are kept in special aviaries with no human imprinting for four to five weeks. Then comes the fun part.

The satellite tags cost about £1,000 and weigh about 50g, the same as ten 20p coins.

On the day the birds are ready to fledge, Mackrill fits them with a harness not unlike a tiny backpack. A falconer’s hood helps keep them calm, “but it’s hard. Their talons are powerful. They are so strong it can take two to three people to hold them.”

AINSLEY BENNETT/FORESTRY ENGLAND

He has about ten minutes to sew the harness straps together across the bird’s chest. Linen thread is best, apparently. “I explained to the woman in the sewing shop what I needed and she said it was the most obscure request she’d ever had.”

Controversy over the eagles’ reintroduction has centred on farmers’ fears they will target livestock. In August a farmer in South Uist claimed that eagles had taken his five Shetland pony foals. Investigators found no evidence to support the claims.

• Crofter blames sea eagles for snatching his Shetland pony foals

The beauty of the satellite tracking, says Mackrill, is that it gives the clearest insight so far into what they are really eating: mainly cuttlefish and carrion, not ponies. “We’ve had zero cases of livestock predations.”

‘Magical’ sightings

Proof of how well white-tailed eagles are fitting into the landscape comes less than ten minutes into a boat trip around Poole Harbour in Dorset.

JULIAN BENJAMIN FOR THE TIMES

There, on a spit of sand, within easy view of the cranes and heavy industry of the Sunseeker shipyard where superyachts are made, and no more than 1,500m from the Tesco Express on Poole quayside, is a white-tailed eagle.

He stands there calmly and for some time, as if posing for all the birders on the boat, the banana yellow of his beak standing out against the grey drizzle of the harbour.

He looks more like the American bald eagle to which he is more closely related, than a golden eagle. He is so close we don’t even need binoculars.

For the birdwatchers on the boat, it’s a magnificent sight. “Like seeing a panda, only better,” jokes one woman.

For me, it’s like meeting a stranger while knowing their entire internet history. Thanks to the project, we can identify this bird as G463. And we know an astonishing amount about him.

He spent his nomadic youth cruising around the Continent, crossing the Channel between Dover and Calais, hanging out in the Netherlands and Denmark. He once spent a wild weekend in Sweden, during a 27-month adventure — the longest of any of the released eagles so far — in which he flew more than 10,500 miles and visited seven countries, before coming home, meeting his life partner, G466, and settling down. She has twice travelled the length of Britain, cruising over Stockport, Manchester and Newcastle to spend the summer around the north coast of Scotland.

The team even have photographs of their courtship. On the day believed to be “the first time they met”, the pair spent the day wheeling 80 miles together around Dorset.

G463 is easy to identify for another reason: he’s missing a leg. It’s not known exactly what happened — possibly an electric shock or entrapment — but a bad day in East Anglia left him without a right foot.

One-footed G463, left, and his partner, G466, in Poole Harbour

MARK WRIGHT

Nevertheless, he’s thriving and the pair raised their first chick, a male, this year. The arrival of an unpaired female in the same area has boosted the team’s hope for a new generation.

“We should set up a table with candles, lay out a nice fish platter,” jokes Paul Morton, who leads the Birds of Poole Harbour expeditions.

Paul Morton

JULIAN BENJAMIN FOR THE TIMES

Dennis Hatwell models the RSPB logo, an avocet, another reintroduction success, on the Birds of Poole Harbour boat tour

JULIAN BENJAMIN FOR THE TIMES

The white-tailed eagle is not the only species to return here. This summer an eagle was spotted stealing a fish from an osprey. It’s a normal interaction that would have been unthinkable until only a few years ago.

“We eradicated those two species and now they are both back,” says Mackrill. “That’s really great to see.”

Over on the Isle of Wight, we wait less than 15 minutes before one of eight young eagles released this year appears on the horizon. Their boxy shape in flight is usually likened to a “flying barn door” but the expression is inadequate. As it lands on a tree in front of us, those vast wings seem more like two extravagant dark curtains. There’s a flash of yellow feet. A nearby buzzard suddenly looks rather mundane.

“When I was growing up on the Isle of Wight, it was a far-fetched dream to see an eagle here,” says says Steve Egerton-Read, the project officer from Forestry England. “But for kids now, it’s normal. These birds are becoming part of the culture again.”

Steve Egerton-Read

JULIAN BENJAMIN FOR THE TIMES

Roy Dennis predicts that white-tailed eagles will be nesting on the Thames within a decade. Mackrill dares to hope the same. “It’s not as fanciful as you might think.”