The verdict from October’s energetic fortnight of fairs and auctions in London and Paris is that the art market is finally coming alive again. Taste is still not wildly experimental, rather there is a “safety first” mindset, as collectors seek institutional support and works with more than a nod to art history. But sales were made, across all categories, providing relief to a beleaguered sector.

In London, the Frieze fairs brought lesser-known artists centre stage, though the highest reported price was for a work made by two 20th-century titans: $6mn for a collaborative painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol — “Highest Crossing” (1984) — which incorporates elements as varied as calligraphy, scratched-out words and a depiction of an alligator (sold through Vito Schnabel Gallery).

Individual prices were higher in Paris, including at auction, and with more heavyweight works at the Art Basel Paris fair. Reported sales here were topped by a two-metre-high, yellowish abstract by Gerhard Richter from 1987, priced at $23mn at Hauser & Wirth, one of several Richter works dotted around the fair, which coincided with the artist’s retrospective at the city’s Fondation Louis Vuitton.

High prices are still the exception to the rule in an uncertain market. In a survey of 3,100 collectors worldwide, written by Clare McAndrew and published by Art Basel and UBS last week, median spend in 2024 was found to be $24,000, with the average at $438,990, skewed upwards by a dwindling boomer generation and collectors in mainland China. The survey, which brought in more female and younger generation art buyers, found a broadening range of taste, and some of the latest trends played out in the London-to-Paris season.

Imagined landscapes Georg Wilson, ‘Strange Pastoral’ (2025), at PIlar Corrias © Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

Georg Wilson, ‘Strange Pastoral’ (2025), at PIlar Corrias © Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

In topsy-turvy times, there is an appetite for escapism through surrealism. Today’s artists, in greater supply and generally less pricey than their 20th-century forerunners, are building momentum with imagined, symbolist landscapes seemingly on every art fair booth this month. Works include the bright, structured forms of Swiss painter Nicolas Party — whose sold-out gallery show at Hauser & Wirth in London is dominated by woodland scenes — and the detailed, heightened fairytale forests by rising star British painter Georg Wilson. Her “Strange Pastoral” (2025), from the same series as an ongoing solo show in Edinburgh’s Jupiter Artland, sold quickly through Pilar Corrias at Art Basel Paris, while imagined landscapes by Sholto Blissett and Pierre Knop were whisked from the booth.

Mystical Nordic art from the estate of the Danish entrepreneur Ole Faarup hit the spot at Christie’s, while this collection’s uncanny and reimagined landscapes by Peter Doig (currently also revived in a solo show at the Serpentine) proved the high spots of London’s auction season. Corrias says that “collectors are increasingly drawn to imagined or re-enchanted landscapes as spaces of escape and reflection. These works offer an alternative to narratives of expansion and extraction.”

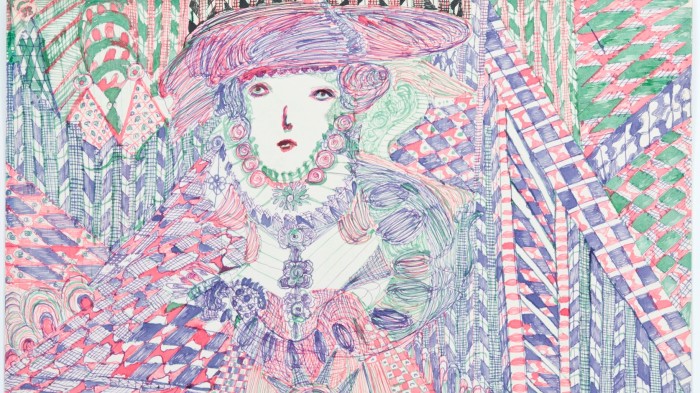

Outsider art

Art from outside the traditional canon is about as experimental as the current market allows, notably through self-taught and indigenous artists. At Frieze Masters, the Gallery of Everything sold out its works by Madge Gill, including a work each to London’s Tate Collection and National Portrait Gallery. The self-taught artist (1882-1961), who featured in the recent Grayson Perry exhibition at the Wallace Collection, comes with a compelling back story. Born Maude Ethel Eades, Gill had a miserable childhood and later turned to drawing while believing she was possessed by a spirit guide. The resulting works, mostly made in ink on card (though there are textiles too), are intricate, obsessive and heavily decorated — often self-portraits in her spirit guide’s name of Myrninerest — expressing “belief coming out of a brush”, says gallery owner James Brett. Such spirituality has latterly been left out of the narratives of revived artists, he says, but is now finding an audience. “In the machine age, there is a thirst for connection,” Brett says.

Photography

Perhaps in another reaction against the pace of technological advances, old-school analogue photography came to the fore this season. Pace Gallery dedicated its Frieze Masters booth to the US gay-scene photographer Peter Hujar and made six swift sales on opening day ($25,000-$45,000). At Art Basel Paris, assemblages by Italian photographer Jacopo Benassi, framed in raw wood and with elements including leather strapping, were selling fast for between €7,500 and €12,000, through Mai 36 Galerie.

Jacopo Benassi, ‘Manifestazione di fiorie farfalle nelle catacombe di Parigi’ (2025) © Courtesy Mai 36 Galerie and the artist. Photo: Davide Paolini

Jacopo Benassi, ‘Manifestazione di fiorie farfalle nelle catacombe di Parigi’ (2025) © Courtesy Mai 36 Galerie and the artist. Photo: Davide Paolini

Art buyers are increasingly drawn to the medium, finds the Art Basel and UBS Global Collecting Survey, which revealed that 44 per cent of respondents had purchased a photograph between 2024 and 2025, up from 16 per cent in 2023. The change partly reflects the nature of the surveyed buyers — women were found to have spent more than double their male counterparts on photography (average $65,000 versus $30,000), while buyers under the age of 60 allocated an average 14 per cent of spend, versus 3 per cent from boomers (aged 61 to 79).

Digital art, while also found to be increasingly in favour in the report, was little in evidence in this season’s big brand fairs, though Pace brought a mesmerising new work of continuous crashing black and white waves to Art Basel Paris, courtesy of the Japanese collective teamLab.

Old masters  John Currin’s ‘Supermoon’ (2025) was placed outside Gagosian’s booth at Art Basel Paris . . . © Gagosian Gallery

John Currin’s ‘Supermoon’ (2025) was placed outside Gagosian’s booth at Art Basel Paris . . . © Gagosian Gallery . . . while inside the booth was Rubens’ ‘The Virgin and Christ Child, with Saints Elizabeth and John the Baptist’ (c1611-14) © Fredrik Nilsen Studio

. . . while inside the booth was Rubens’ ‘The Virgin and Christ Child, with Saints Elizabeth and John the Baptist’ (c1611-14) © Fredrik Nilsen Studio

Old is the new new. Gagosian gallery broke the Art Basel Paris rule to show art made “after 1900” by bringing a fleshy and deft holy family scene by Peter Paul Rubens from c1611-14. The gallery’s accepted reasoning was that many of today’s most in-vogue artists reference their past peers. Outside its booth, the gallery made the point with a new painting by John Currin, of three even fleshier women standing in a moonlit forest (more symbolism), while opposite the Rubens was one of Jeff Koons’s so-called “gazing ball” works, a reflective blue sphere placed in front of a replica of a work by the French baroque painter Nicolas Poussin.

Prized old masters are hardly cheap — the undisclosed Rubens price is probably close to the $7.1mn for which the work sold at auction in 2020 — but newer buyers are less baffled by the reasoning behind such valuations than by some of the prices that newer art can command. “For younger collectors, say those in tech on the West Coast, contemporary art can be more opaque. Knowing someone’s biography and historic weight is often more approachable and comes with a story,” says Bernie Lagrange, director at Gagosian Art Advisory. “Art history is hanging on,” he says.