This study hypothesized that there would be a negative association between the quality of glycemic control and the presence of TB infection among HIV-negative Nepalese patients with DM. Even with a suboptimal tool to diagnose TB infection, such as TST, poor glycemic control more than triples the odds of TB infection.

Earlier studies exploring an association between poor glycemic control and TBI have shown inconsistent results. Some studies have shown a positive association between glycemic control and TBI. In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data from 4215 individuals aged ≥ 20 years in the United States, investigators found that the patients with poor glycemic control had a higher risk of developing TB infection (aOR 1.13, 95% CI 1.04–1.22) [18]. Another study of 600 patients with diabetes seeking care at the primary healthcare services in two Mexican cities found that people with diabetes with poor glycemic control were at higher risk of TB infection as compared to those with good glycemic control (aOR = 2.52 [95% CI 1.10–8.25], p-value 0.04) [19]. The magnitude of the risk reported in this (aOR 2.52) is comparable to the adjusted OR of our study (aOR 3.3). Similarly, in a household survey in two rural villages in eastern China, investigators screened 5405 eligible residents aged >5 years for TB disease, TB infection, and diabetes mellitus and found that individuals with severe DM was associated with increased risk of TB infection (aOR, 1.41, 95% CI, 1.05–1.90, p = 0.022) [17]. The lower estimated risk reported in this study, despite the similar high TB incidence setting and comparable confounders adjusted in the multivariate models, could be due to the differences between study populations. Our study in Nepal was conducted among patients with diabetes who presented to the hospital for care. So, they are more likely to have poorer glycemic control and/or comorbidities as well. The study in China was, instead, a population-based survey conducted among the individuals in the communities. They are, therefore, more likely to have no diabetes or relatively better-controlled diabetes as well as have fewer or no comorbidities.

On the other hand, other studies did not find any significant association between glycemic control and TST positivity. In a study of 299 diabetic adults aged ≥ 18 years presenting at a university hospital in rural/suburban Malaysia, investigators found no significant difference in HbA1C between the patients with and without TBI (aOR 0.98, 95% CI 0.80, 1.20, p = 0.84) [20]. Similarly, in a community-based study in Taiwan, investigators studied 2948 patients with diabetes and 453 individuals from the community as a comparison group and found that neither the long length of time since diabetes diagnosis (in years) nor poor glycemic control affected the risk of TBI [16]. Several explanations could be offered for this observation; the TB and diabetes incidence in Tawain are lower than that in Nepal, the study was conducted among the community-based study population with likely lower diabetes prevalence or better glycemic control as compared to the hospital-based study population and IGRA was used to identify TBI among the study participants, which has higher specificity than TST thereby leading to the lower prevalence of TBI. However, when stratified according to both the duration as well as glycemic control, it was revealed that poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes for less than 5 years was significantly associated with TBI. This, in turn, could be due to the use of IGRA to diagnose the TBI status, which is more sensitive when the TB infection is recent because the activated lymphocytes and effector memory T cells producing IFN-γ persist in circulation only for a limited time after the antigen has been cleared [26].

In a country like Nepal, with a high prevalence of TB and an annual risk of TB infection (ARTI) of 0.86% (95% CI 0.49–1.23), by the time one reaches diabetes age, one is likely to have been repeatedly exposed to TB. Therefore, the high prevalence of TBI and TB disease found in this study likely reflects a combination of increased exposure and susceptibility. Therefore, patients with poor glycemic control, especially when they have had long-standing diabetes, could be an important group that can be targeted for systematic TBI screening and TB preventive treatment [27].

This study demonstrates that TST remains a valuable tool, even in individuals with DM, and when stratified by glycemic control measures such as HbA1C levels, it can provide valuable insights into TB infection risk and guide targeted TPT interventions. Timely screening of these individuals for TBI could, therefore, provide an opportunity to intervene early, thereby potentially averting the progression to TB disease and improving glycemic control as well.

Persons with DM are already prioritized in the national TB screening policy, and 2.5% of people screened for eligibility in our study were already receiving TB treatment. However, the high burden of TB disease (4.01%) among these people with diabetes indicates that screening for active disease may not be sufficient, and secondary prevention efforts may be needed to address the high burden. For TB control programs, therefore, the findings of this study suggest that systematic TBI screening and TB preventive treatment could be expanded to diabetic individuals with poor glycemic control, along with other high-risk populations, to help curb the progression of TB infection to TB disease. However, several dimensions need to be considered before the programmatic implementation of targeted TB infection screening and TB preventive treatment, which include the organization of the resources and supplies needed, the added costs incurred to the patients and the programs, and acceptance by doctors and infected persons.

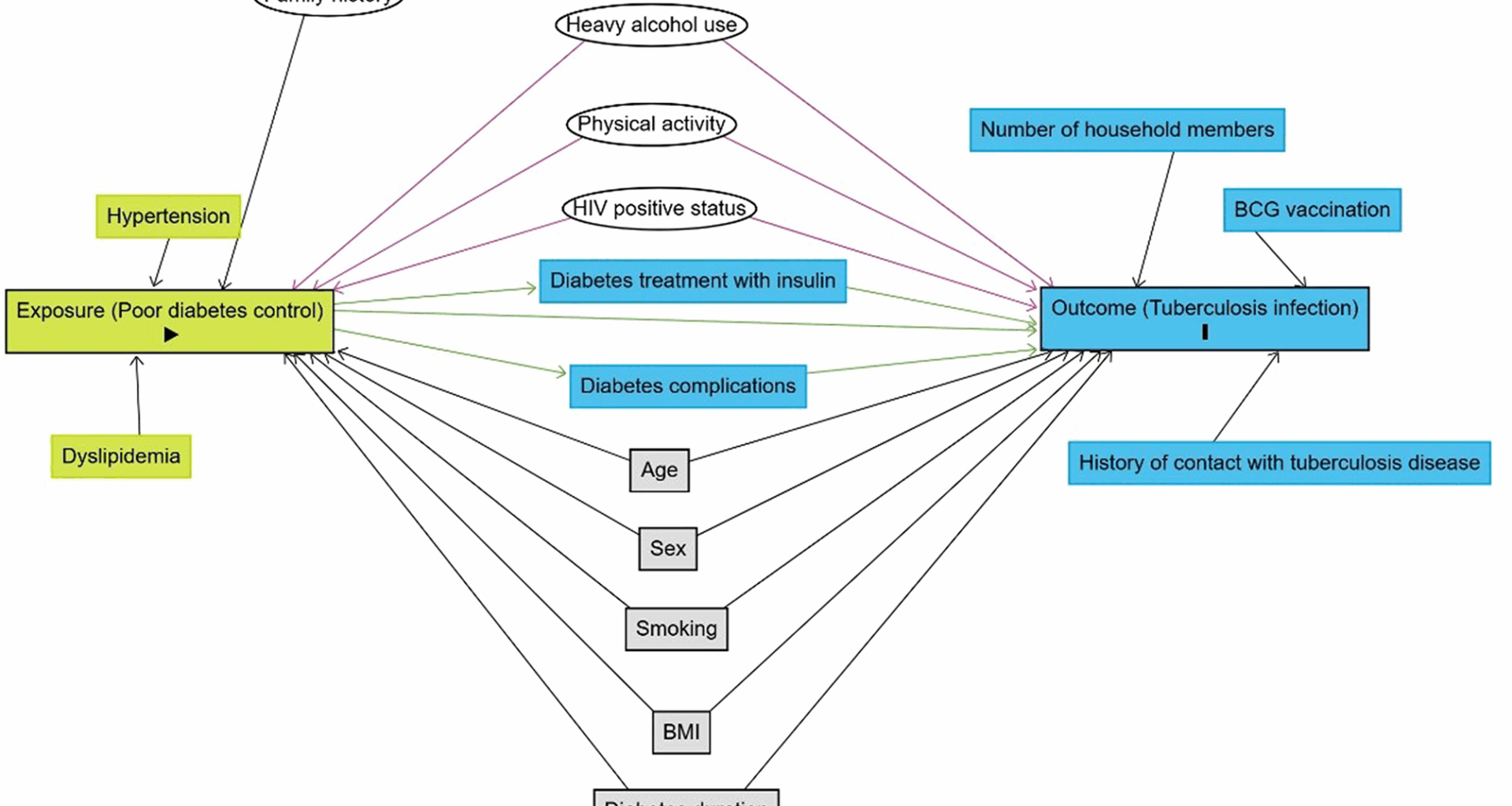

The study has methodological and analytical strengths and limitations that merit consideration as they impact the interpretation of the results. The use of both symptoms as well as chest X-ray to screen for TB disease, followed by sputum GeneXpert MTB/Rif assay for those who screen positive, provided a robust prevalence estimate and helped to ensure diagnosis of the diverse DM-associated TB phenotypes. The exclusion of individuals with potential confounding factors, such as people living with HIV and those with other immune-compromised conditions, reduced the risk of confounding.

The TST, as a tool to establish TB infection, may yield both false positives due to BCG vaccination and non-tuberculous mycobacteria, as well as false negatives due to immune-compromised status, particularly those with very poor glycemic control (Supplementary material 8). Recently, WHO approved skin tests for TB diagnosis based on Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific antigens (ESAT6 and CFP10), which offer a specificity similar to Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) [28]. Such tests are particularly useful in resource-constrained settings like Nepal, where BCG vaccination coverage is high (92%), and non-tuberculous mycobacteria contribute to false-positive TST results [29]. Metformin is prescribed to nearly all the people with diabetes in Nepal, and 99% of study participants received metformin, so the study results are generalizable to persons taking metformin. However, the overall findings should be interpreted with caution as this study was conducted among patients from a single centre, which may not fully represent the broader diabetic population in Nepal. Due to the cross-sectional study design, it could not be determined whether the TB infection occurred before or after diabetes developed or when the glycemic control worsened.

This study contributes to our understanding of the different ways poor glycemic control impacts TB while identifying future research needs. Both TST and IGRA have limited ability to predict the development of TB disease even in healthy populations. Therefore, this study highlights the need for tests that predict the progression into TB disease with sufficient accuracy. Further studies examining longitudinal data could provide some insights into the rate of progression of diabetic individuals with TB infection to TB disease. Contextualized studies that further explore the accuracy, safety, acceptability, and feasibility in different settings could facilitate their uptake.