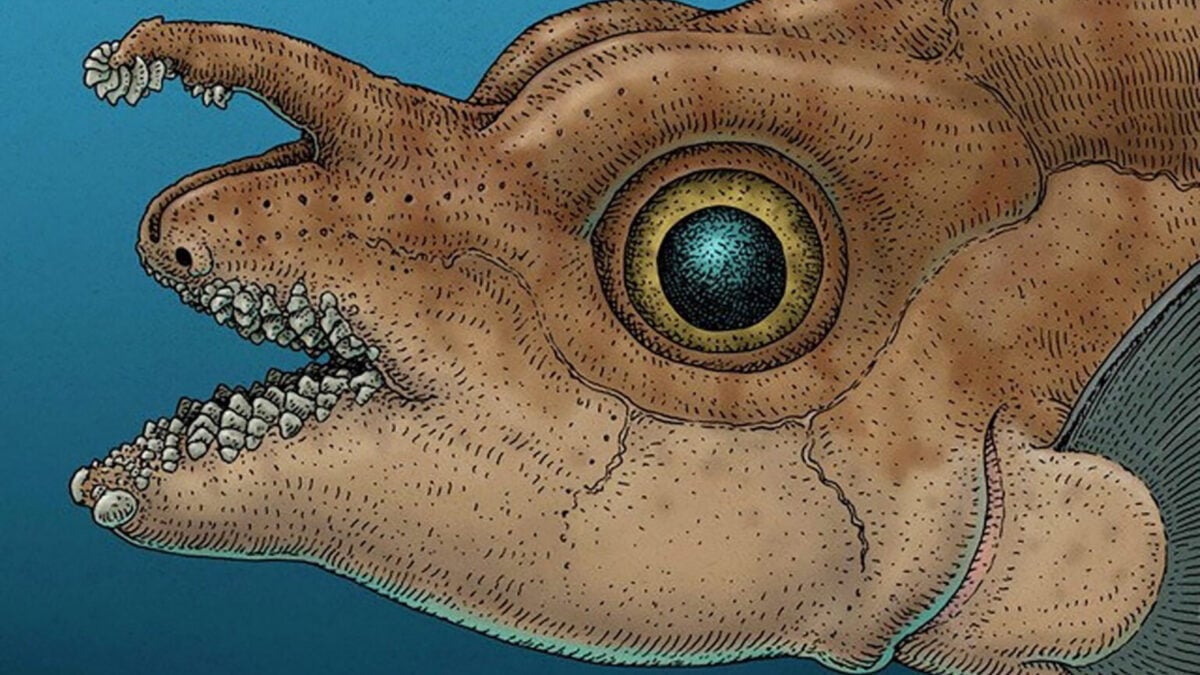

Spotted ratfish are scaleless, rabbit-faced deep-sea fish, about two feet (61 centimeters) long, and native to the northeastern Pacific Ocean. As if that wasn’t a strange enough description, these distant shark cousins also feature teeth on their foreheads.

While a number of marine animals, such as sharks, rays, and whale sharks, have external tooth-like structures called denticles, it turns out the spotted ratfish’s toothy features are straight-up true teeth, as true as the ones in your mouth. And they use them for sex.

Researchers have revealed that the structures on the male spotted ratfish’s tenaculum—an appendage on its forehead—are real teeth. This discovery could have significant implications for the evolutionary history of teeth. Plus, researchers now get to wonder, in what other funky places could teeth be growing?

“Male chimaeras develop an articulated cartilaginous facial appendage, the tenaculum, which is covered in an arcade of tooth-like structures,” the researchers wrote in a study published last week in the journal PNAS. “These extraoral teeth remain poorly understood, and their evolutionary origin is unclear. We investigate the development of the tenaculum and its teeth throughout the ontogeny of the Spotted Ratfish, Hydrolagus colliei.”

Underwater sex is hard

Spotted ratfish erect their tenaculum to scare off competition and hold onto females’ pectoral fins while mating. After all, it must be hard to make love underwater with no arms. So much so that these deep-ocean fish are endowed with a second tool—denticle-covered pelvic claspers—to make sure their mate doesn’t float away. When the tenaculum is erect, it’s hooked and barbed with up to seven or eight rows of retractable and flexible teeth. When it’s not in use, however, it’s small and white.

“This insane, absolutely spectacular feature flips the long-standing assumption in evolutionary biology that teeth are strictly oral structures,” Karly Cohen, a biologist at the University of Washington, said in a university statement. “The tenaculum is a developmental relic, not a bizarre one-off, and the first clear example of a toothed structure outside the jaw.”

To investigate whether the tenaculum’s structures were denticles or real teeth, the researchers studied the tenaculum of hundreds of fish. They also compared the fish to their ancestral fossils. These approaches revealed that both male and female ratfish develop the start of a tenaculum, but only in males does it grow into a little white pimple (ew, not my description) that extends on the forehead. The structure attaches to jaw muscles, breaks through the surface of the skin, and grows teeth. Thank goodness my pimples have never done that.

The tenaculum’s teeth are rooted in the dental lamina—jaw tissue that, until now, researchers hadn’t seen anywhere else. “When we saw the dental lamina for the first time, our eyes popped,” Cohen explained. “It was so exciting to see this crucial structure outside the jaw.”

Real teeth

Part of the excitement was surely due to the fact that skin denticles don’t have a dental lamina, suggesting that the tenaculum’s teeth are exactly that: teeth. The researchers further bolstered this theory with genetic evidence, revealing that genes linked to vertebrate teeth were expressed in the tenaculum. These genes were not expressed in the denticles. Furthermore, the team identified hints of teeth on related species’ tenaculum in the fossil record.

“We have a combination of experimental data with paleontological evidence to show how these fishes coopted a preexisting program for manufacturing teeth to make a new device that is essential for reproduction,” said Michael Coates, a co-author of the paper and the University of Chicago’s chair of organismal biology and anatomy.

“Chimeras offer a rare glimpse into the past,” Cohen concluded. Chimaeras are a group of cartilaginous fish, including spotted ratfish. “I think the more we look at spiky structures on vertebrates, the more teeth we are going to find outside the jaw.”