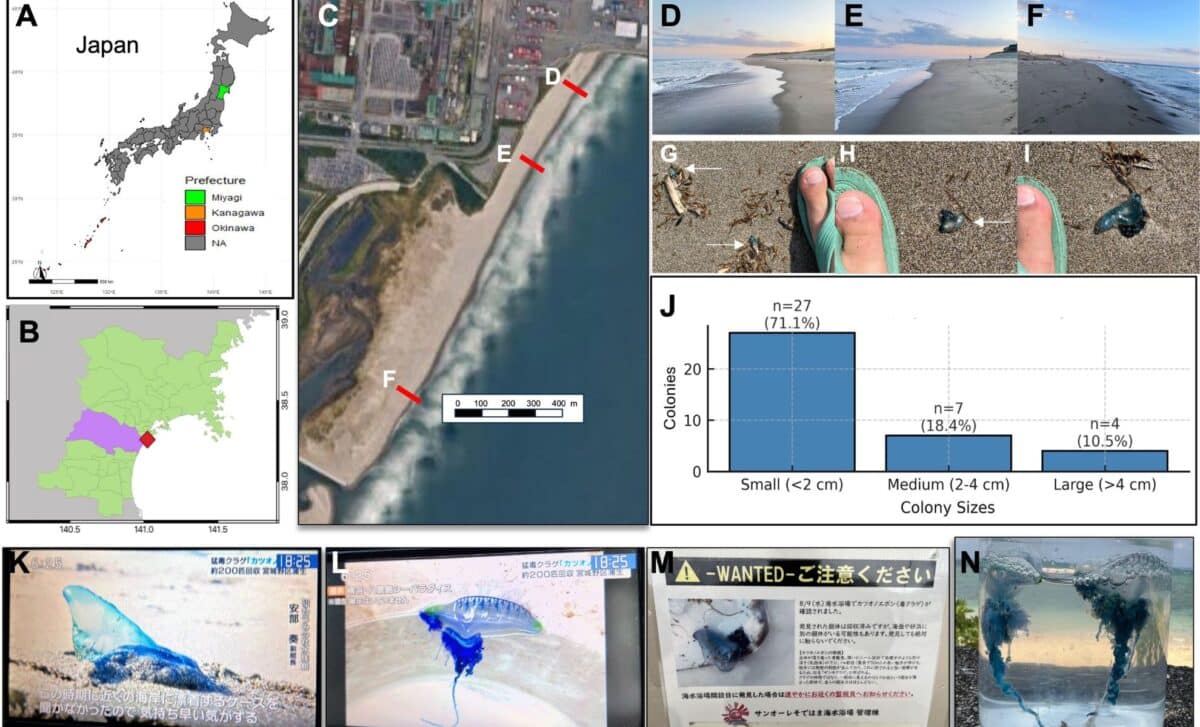

The discovery, made by a student team from Tohoku University, offers new insight into how marine organisms are responding to rising sea temperatures in the Pacific. The presence of P. mikazuki in Sendai Bay, a region once considered too cold for this genus, is prompting scientists to revisit long-held assumptions about species range and biodiversity in Japanese waters.

Physalia utriculus, known locally in the warmer southern seas, was once thought to be the only Physalia species in Japan. But that changed in June 2024, when several striking blue specimens were found stranded on Gamo Beach in Miyagi Prefecture. Their unfamiliar morphology caught the eye of student researcher Yoshiki Ochiai, who—by chance—spotted one while conducting unrelated fieldwork. “I scooped it up, put it in a ziplock bag, hopped on my scooter, and brought it back to the lab,” he recalled in an interview included in the Frontiers in Marine Science article published on October 30, 2025.

A Name Rooted in Local History

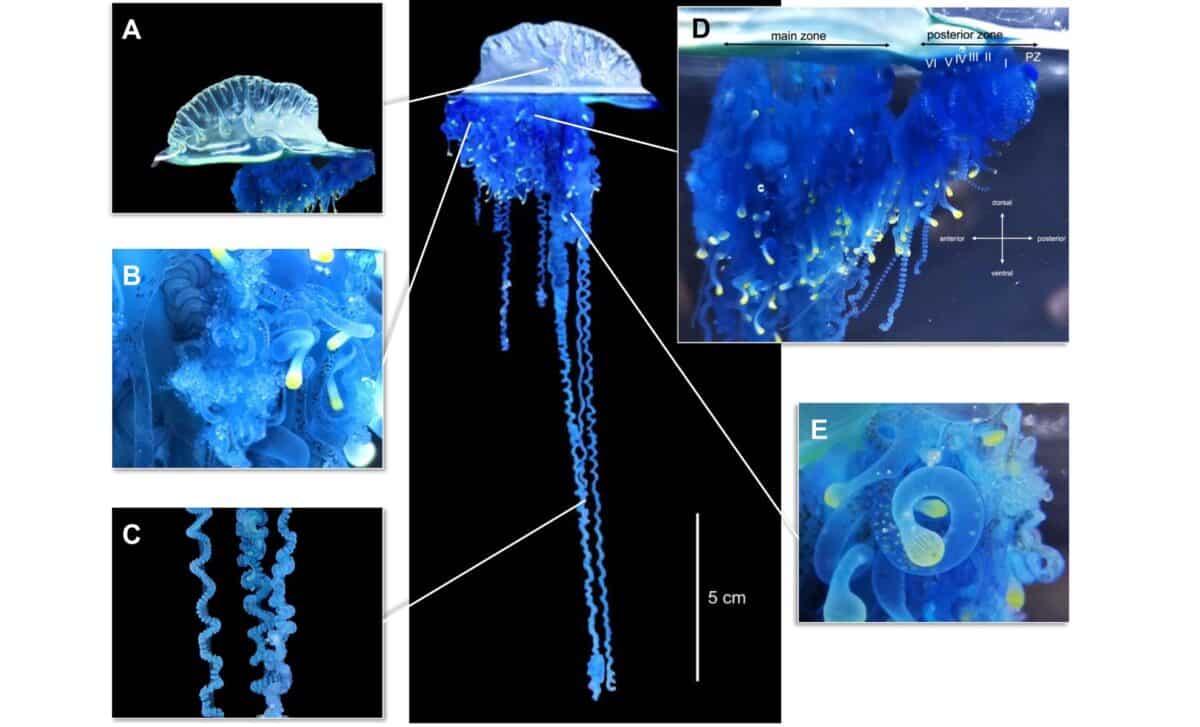

The newly described jellyfish bears a name steeped in regional heritage. Physalia mikazuki, or the “crescent helmet man-of-war,” pays tribute to the famed samurai lord Date Masamune, whose distinctive crescent-shaped helmet has long symbolized Sendai. This choice reflects not only the jellyfish’s arched, sail-like float but also its geographic identity.

According to lead taxonomist Chanikarn Yongstar, the classification process was exhaustive. She compared each part of the organism to historical illustrations in century-old biology manuscripts. “I looked at each individual part, comparing its appearance to old tomes where scholars drew out the jellyfish anatomy by hand. A real challenge when you look at just how many tangled parts it has.” she said. The team analyzed morphological traits, such as tentacle thickness, zooid structure, and color patterns, and cross-referenced them with molecular data from global Physalia samples.

What they found was conclusive. DNA sequencing of the 16S rRNA and COI mitochondrial gene regions confirmed the jellyfish belonged to a distinct genetic clade, separate from known Physalia species such as P. physalis, P. minuta, and P. utriculus. These results led to its official designation as a new species, making P. mikazuki the first Physalia ever formally described from Japanese waters.

Tracing the Path Northward

The presence of this tropical cousin in northern Japan was no random drift. Oceanographic simulations run by the Tohoku University team traced a likely route using the OceanParcels Lagrangian model. According to researcher Muhammad Izzat Nugraha, the particles in the simulation, likened to floating “red beach balls”, drifted along the Kuroshio Current, reaching Sendai Bay in about 30 days. Some continued farther north to Aomori Prefecture within 75 days.

This trajectory aligns with recent sea-surface data from HYCOM (Hybrid Coordinate Ocean Model) , which showed that the Kuroshio Current extended about 100 km farther north between 2022 and 2024. During that time, northern waters recorded anomalous warming of 2–4°C, creating conditions that allowed tropical organisms to survive farther from the equator. These findings suggest that marine species like P. mikazuki are not only drifting farther but also enduring longer in temperate zones.

Crucially, these conclusions are backed by historical monitoring. Long-term records from Sendai Bay had shown no Physalia sightings prior to 2023, reinforcing the theory that its presence is a recent, and environmentally driven, phenomenon. As noted in the same study, “Despite regular field studies… Physalia was never observed at Gamo Beach until its discovery in June 2024.”

Venom, Visibility, and Vigilance

While visually stunning, Physalia mikazuki brings practical concerns. Like its relatives, it is venomous. Its tentacles can extend several meters and deliver intensely painful stings to humans. Public health warnings followed the initial discovery, with alerts posted at local beaches, and coverage on regional TV stations raising awareness of the jellyfish’s unexpected appearance.

According to marine biologist Ayane Totsu, the jellyfish represents both risk and research potential. “These jellyfish are dangerous and perhaps a bit scary to some, but also beautiful creatures that are deserving of continued research and classification efforts,” she noted in the Frontiers in Marine Science article.

The study also underscores a larger ecological narrative. As warming oceans push species across former boundaries, regions like Tohoku, previously shielded by cooler currents, may increasingly become new frontiers for tropical or subtropical organisms. Ongoing monitoring and species identification efforts will be key to understanding how these shifts affect marine food webs, biodiversity, and beach safety. In the meantime, Physalia mikazuki remains both a scientific milestone and a warning, an emblem of a warming ocean and a reminder of just how quickly life in the sea can change.