This retrospective before-and-after study of more than 4,400 patients who underwent cardiac and/or thoracic aortic surgery with CPB suggests that routine administration of low-dose intraoperative TXA in all patients significantly reduced postoperative bleeding without increasing the risk of seizures or thrombotic complications. The results of this study reinforce the existing evidence for the use of TXA in cardiac surgery, for which data had been relatively limited compared to other surgical settings. Additionally, the marked reduction in the proportion of patients with ML > 15% in ROTEM following the implementation of this protocol provides valuable supporting evidence for the hemostatic benefits of this approach.

The evidence that TXA reduces blood loss and transfusion requirements in surgical patients first emerged in cardiac surgery nearly two decades before the BART trial [15, 16]. Subsequent studies, primarily in noncardiac surgery, have consistently reported similar findings across various surgical fields, including orthopedic, head and neck, urologic, and breast surgery [5, 6]. Recently, the ATACAS multicenter randomized controlled trial of 4,631 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting and/or cardiac valve replacement further confirmed these benefits [17]. Based on this body of evidence, current guidelines strongly recommend the use of TXA and other antifibrinolytics (Class I recommendations) to reduce blood loss and transfusion requirements in cardiac surgery [7, 8]. Although our study was not a randomized trial, it provides additional supporting evidence in the field of cardiac surgery by demonstrating that the routine implementation of even low-dose intraoperative TXA in more than 4,000 patients undergoing cardiac surgery was associated with a significant reduction in blood loss and transfusion requirements compared to patients in the pre-implementation period. Regardless of the statistically significant results, the numerical reduction in chest tube output was not drastic; however, considering that postoperative bleeding after cardiac surgery is influenced by a wide range of factors, our finding—that a simple single measure such as TXA implementation produced even a modest gain without any increase in adverse events—remains clinically meaningful.

The emphasis on our findings, derived from a low-dose TXA regimen, stems from concerns about TXA-related adverse effects. Given its antifibrinolytic properties, TXA has been linked to the potential risk of thrombotic complications, including bowel ischemia, pulmonary thromboembolism, deep vein thrombosis, and ischemic stroke. However, current guidelines only recommend the use of TXA in cardiac surgery but do not specify an appropriate dose that provides sufficient hemostatic efficacy while minimizing adverse events [7, 8]. The CRASH-2 trial demonstrated that administering TXA at a dose of 1 g twice in trauma patients did not increase thrombotic complications compared with placebo [18]. Similarly, the WOMAN trial found no increased thrombotic risk with a comparable TXA regimen for postpartum hemorrhage [19]. In noncardiac surgery, the recent POISE-3 trial reported that a 1 g bolus at the beginning and end of surgery significantly reduced the composite bleeding outcome without increasing thrombotic complications [20]. In cardiac surgery, the ATACAS trial evaluated TXA at doses of 50 or 100 mg/kg administered at anesthesia induction and found no significant difference in thrombotic complications compared with placebo [18]. Recently, the OPTIMAL trial was the first randomized controlled trial to compare different TXA dosing strategies during cardiac surgery (n = 3,031) [21]. It showed that a high-dose regimen (30 mg/kg bolus, 16 mg/kg/h maintenance, and 2 mg/kg CPB prime) led to a modest reduction in transfusion rates and met non-inferiority criteria for a composite complication outcome compared to a low-dose regimen (10 mg/kg bolus, 2 mg/kg/h maintenance, and 1 mg/kg CPB prime) [21]. Nevertheless, current evidence is insufficient to conclude that higher doses should be universally adopted, highlighting the need for further research on various dosing regimens. Indeed, meta-analyses have suggested that beyond a certain threshold (which is yet to be determined), additional TXA may not provide further hemostatic benefits, whereas the risk of adverse events is expected to increase linearly with dose escalation [22, 23]. Our study employed a modified regimen with a lower bolus dose of TXA (5 mg/kg) but a higher maintenance dose (5 mg/kg/h) than the low-dose arm of the OPTIMAL trial, yet thrombotic complications remained comparable to those in the non-TXA group. At the time our regimen was established, we considered that reducing the bolus dose while using a relatively higher infusion rate could avoid excessively high peak plasma levels and still achieve the plasma concentration of 20 µg/ml known to maintain antifibrinolytic activity throughout CPB [24, 25]. Compared with no TXA use, this regimen demonstrated clinically meaningful effects in our study; however, future studies directly comparing this regimen with protocols that use lower maintenance infusion rates are warranted, as the optimal protocol remains undefined.

Although the interrupted time series analysis did not show a significant intercept change in the incidence of reoperation for bleeding, logistic regression after IPTW indicated a statistically significant increase in risk (see Supplementary Material, Table S4). Nevertheless, compared with conventional regression analysis, interrupted time-series analysis has been regarded as a more robust quasi-experimental design for evaluating changes before and after the implementation of an intervention in nonrandomized settings [14, 26, 27]. Accordingly, we believe greater weight should be placed on the interrupted time series analyses, as they more reliably reflect the impact of TXA implementation. In addition, given the large quarterly variation in incidence (data not shown), this finding may have occurred by chance or may reflect a shift in practice toward more proactive reoperation in less severe bleeding scenarios, as suggested by recent evidence that early re-exploration for postoperative bleeding after cardiac surgery may improve outcomes [28, 29].

Another important TXA-related adverse effect to be considered is seizures. In the ATACAS trial, although the overall incidence of postoperative seizures was low, TXA was significantly associated with a higher risk compared to placebo (0.7% vs. 0.1%; risk ratio [95% CI], 7.62 [1.77–68.71]), drawing considerable attention [17]. The proconvulsant effect of TXA was identified in animal experiments decades ago [30], and a number of possible mechanisms have been proposed [31, 32]. Previous studies have also suggested that TXA may have a stronger proconvulsant effect than ε-aminocaproic acid and aprotinin [33, 34]. Similar to thrombotic complications, seizure risk appears to be dose-dependent, with a higher incidence observed at moderate to high doses (24–100 mg/kg) [35, 36]. However, the optimal dose that minimizes the seizure risk remains unknown. Even the OPTIMAL trial, the only randomized trial to date comparing different TXA doses, was not adequately powered to assess seizure risk, highlighting the need for further investigation [21].

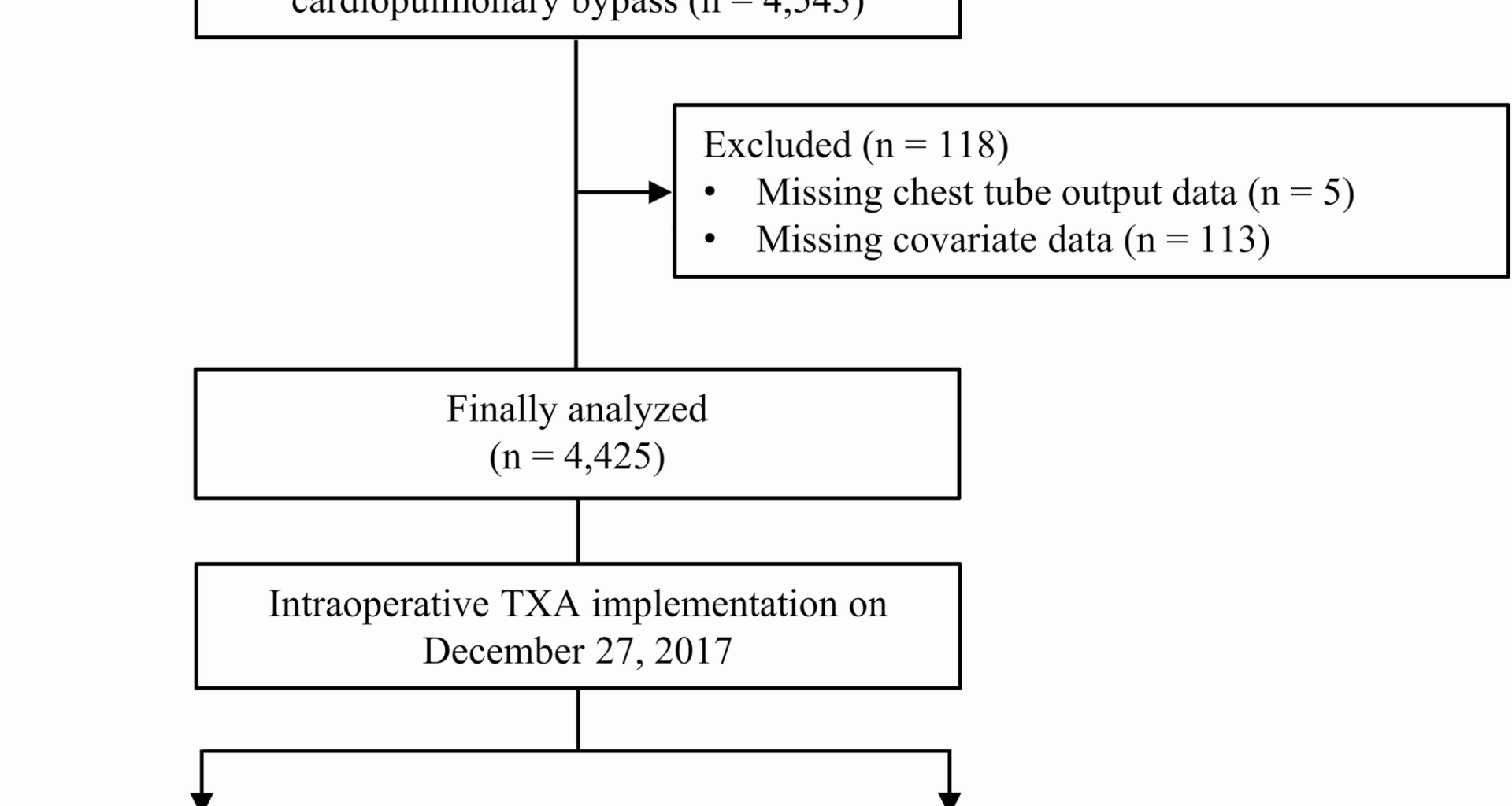

The present study had several limitations. First, although this study adopted a before-and-after design with IPTW adjustment to mitigate bias, the inherent nature of this retrospective study suggests that uncontrolled confounders may have influenced the results. Specifically, even with the sensitivity analysis restricted to patients within a short period before and after TXA implementation, potential temporal confounding from advances in surgical techniques or perioperative management cannot be entirely ruled out. Second, at our institution, the majority of cardiac surgeons perform coronary artery bypass grafting using the off-pump approach. Owing to concerns regarding thrombotic complications in these patients, they were excluded from the routine intraoperative TXA policy at the time of implementation. The 2021 North American guidelines recommend TXA to reduce bleeding and transfusion requirements in this subgroup (Class II), based on small single-center randomized controlled trials by Taghaddomi et al. [37] and Wang et al. [38]. However, evidence for the efficacy and safety of TXA in off-pump cardiac surgery remains even more limited than that in CPB-assisted surgery [7]. Third, ROTEM data were available for approximately one-third of the study population. Nevertheless, given that this study was not a randomized trial and merely indicated an association, the ROTEM findings provide indirect supporting evidence for a potential causal relationship between intraoperative TXA implementation and reduced postoperative blood loss.

This retrospective before-and-after study indicated that routine implementation of even low-dose intraoperative TXA in cardiac surgery is associated with a significant reduction in bleeding and transfusion requirements postoperatively without any increased risk of thrombotic complications or seizures. Our study adds valuable data specific to cardiac surgery, where the data on optimal dosing remains particularly limited. Further research is warranted to determine the optimal balance between efficacy and safety of TXA dosing during cardiac surgery.