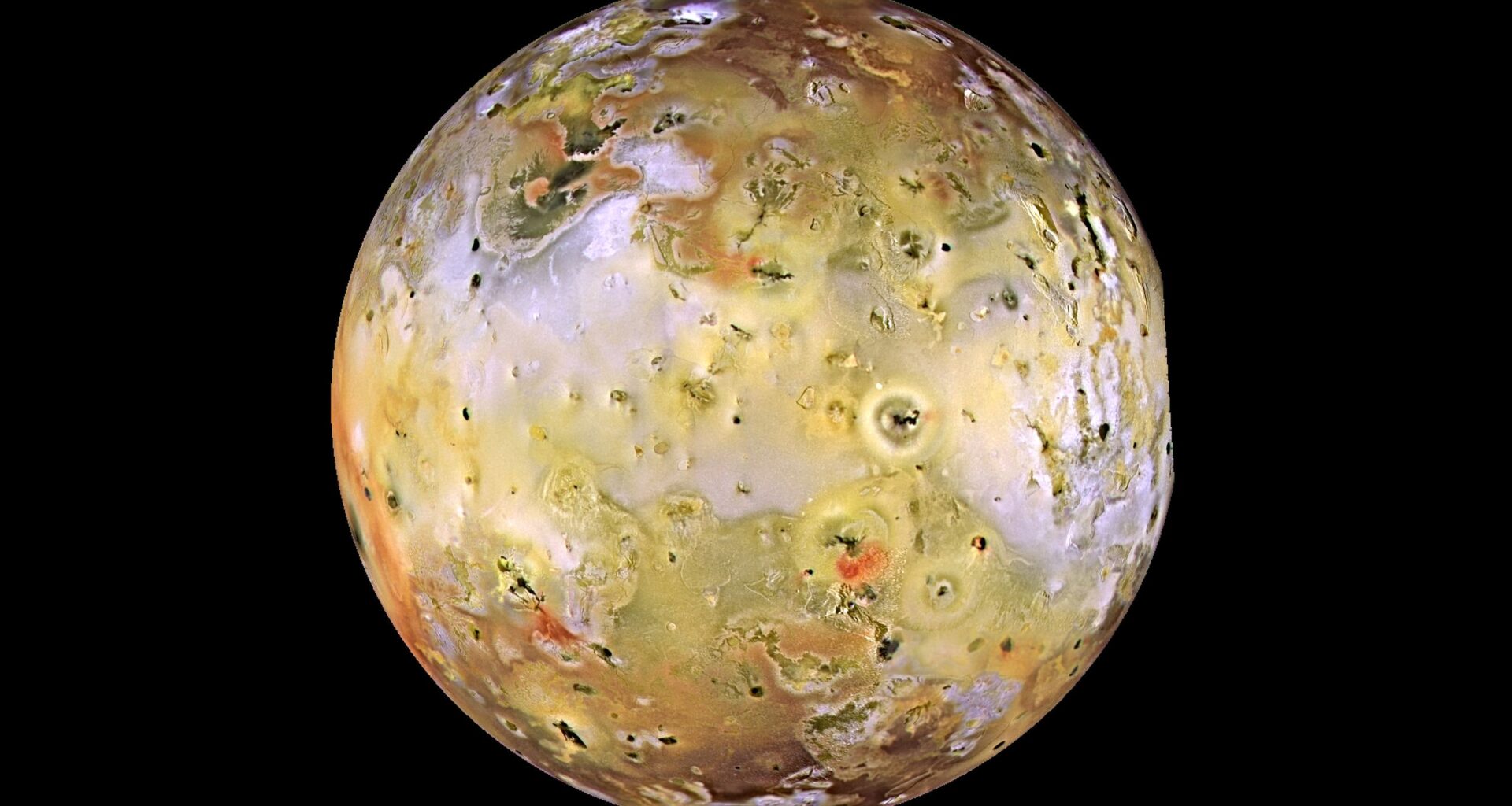

Using data from NASA’s Juno spacecraft, scientists have discovered that the solar system’s most volcanic body is even hotter than we thought. In fact, Jupiter’s moon Io could be emitting hundreds of times as much heat from its surface as was previously estimated.

The reason for this underestimate wasn’t due to a lack of data, but was a result of how Juno’s data was interpreted. The results also demonstrate that about half of the heat radiating from Io comes from just 17 of 266 the moon’s known volcanic sources. The team behind this research thinks that this clear concentration of heat, rather than a global emission, could suggest that an Io-wide lava lake may not exist beneath the surface of this moon of Jupiter as has previously been theorized.

“In recent years, several studies have proposed that the distribution of heat emitted by Io, measured in the infrared spectrum, could help us understand whether a global magma ocean existed beneath its surface,” team leader Federico Tosi of the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) said in a translated statement. “However, comparing these results with other Juno data and more detailed thermal models, we realized that something wasn’t right: the thermal output values appeared too low compared to the physical characteristics of known lava lakes.”

You may like

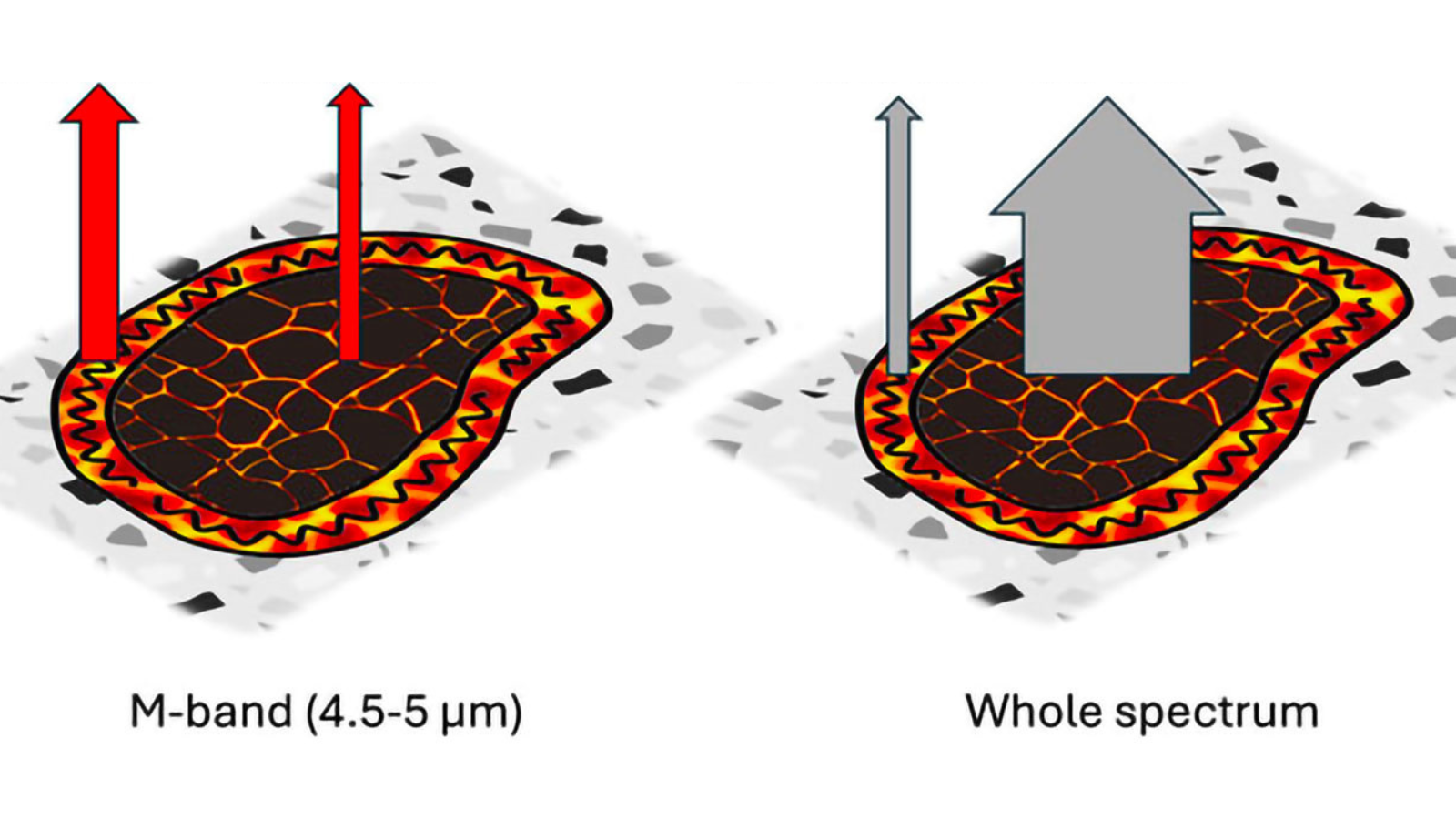

Tosi continued by explaining that until now, studies of Io have focused heavily on a specific band of infrared light known as the M-band. M-band data collected by the Jovian InfraRed Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) aboard Juno have been invaluable in identifying the hottest regions of Io and thus for understanding its volcanism, but Tosi says the measurements collected in this spectral band could have influenced previous heat estimates

“The problem is that this band is sensitive only to the highest temperatures, and therefore tends to favor the most incandescent areas of volcanoes, neglecting the colder but much more extensive ones,” Tosi said. “In practice, it’s like estimating the brightness of a bonfire by observing only the flames and not the surrounding embers: you capture the brightest spots, but you don’t measure all the energy actually emitted.”

Seeing Io in a different light

Reconsidering their approach to analyzing Juno’s JIRAM data changed the team’s view of the structure of Io’s lava lakes. They found that most of Io’s volcanoes are not uniformly hot but instead possess a hot and bright outer ring with a cooler, solid central crust. This latter region is less bright in the M-band of infrared light but covers a larger surface area, allowing it to emit an enormous amount of heat.

“When this ‘hidden’ component is also considered, the actual heat flux is up to hundreds of times higher than that calculated by analyzing the M-band alone,” Tosi continued. “This is a significant leap, because it changes the scale of the satellite’s [Io’s] energy balance.”

This could have implications for the suggested global ocean of magma below the surface of Io, but Tosi is clear that the existence of this feature isn’t something that can be completely ruled out by this research. In fact, he theorizes that M-band JIRAM data can’t be used to confirm this magma ocean.

“Our caution, therefore, is well-founded: we’re not saying that such an ocean doesn’t exist, but that it can’t be deduced from these observations,” Tosi said. “It’s important to recognize the limitations of the available data before drawing too strong conclusions on such a complex issue.”

A comparison of heat emitted by Io lava pools seen in the M-band and in the whole spectrum of infrared light. (Image credit: Alessandro Mura/ INAF)

Unfortunately, it may be a while before scientists get such a good look at Io again, so the question of its global magma ocean may remain unanswered.

You may like

“In 2023 and 2024, Juno performed the closest and most detailed observations of Io ever obtained by a spacecraft. In the coming year, however, the natural evolution of the spacecraft’s orbit will not allow for such close passes again,” Tosi said. “Future missions to the Jovian system, such as ESA’s Juice and NASA’s Europa Clipper, will not be able to observe Io with comparable spatial resolution, as they will be primarily dedicated to Ganymede and Europa.

“Nevertheless, monitoring Io remains crucial.”

He added that the team’s findings should provide a framework that can be used to more accurately interpret even remote spacecraft observations of Io. This could finally help researchers get to the bottom of why this Jovian moon is so violently volcanic.

“Looking ahead, this experience could also inform the design of future missions specifically dedicated to Io, which could finally directly observe the processes that fuel the most intense volcanism in the solar system,” Tosi concluded.

The team’s research was published on Wednesday (Nov. 5) in the journal Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences.