On Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, a groundbreaking discovery by researchers from Chalmers University of Technology and NASA is challenging the very foundations of chemistry — while offering new clues about how life might have begun on Earth.

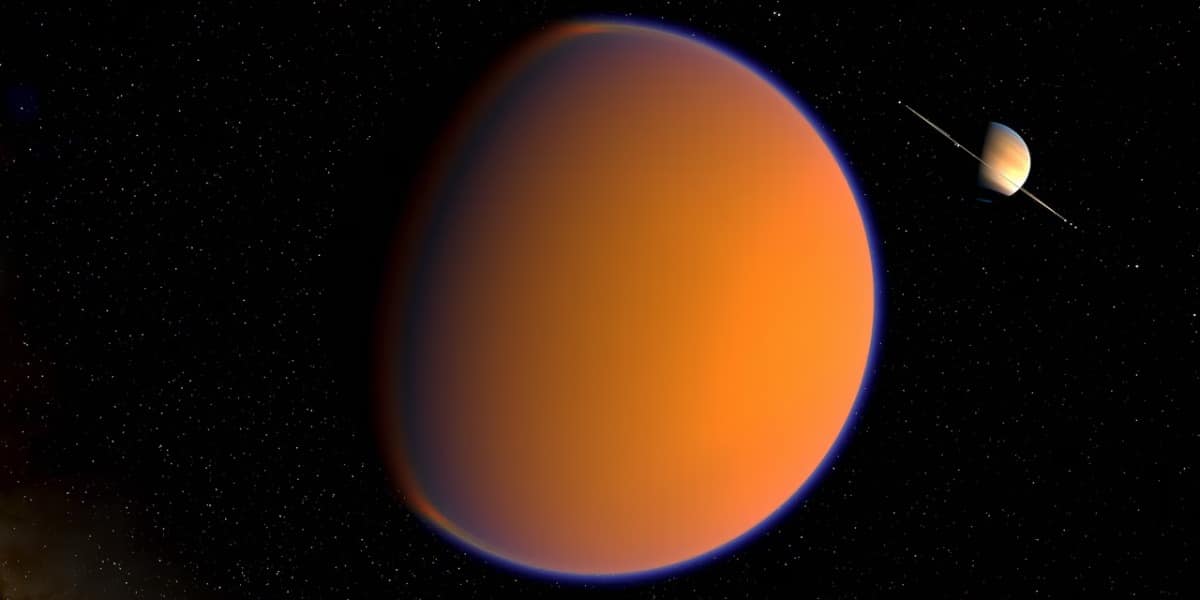

For years, Titan has fascinated scientists because of its resemblance to early Earth. With an atmosphere thick in nitrogen and methane, and a surface carved by lakes and seas of liquid hydrocarbons, it provides a natural window into what our planet may have looked like billions of years ago.

Titan: a natural lab for the origins of life

Cold, dense, and shrouded in haze, Titan’s environment mirrors the conditions that may have existed on the young Earth. By studying its chemical reactions, scientists hope to trace the earliest steps that could have led to life. Titan, in this sense, acts as a living laboratory — a place to explore how complex chemistry emerges under alien conditions.

A discovery that breaks chemistry’s rules

In a remarkable twist, researchers found that substances long believed to be incompatible — like oil and water — can, in fact, interact under extreme conditions. They discovered that hydrogen cyanide, a polar molecule abundant in Titan’s atmosphere, can form crystals with methane and ethane, both nonpolar molecules.

This finding overturns one of chemistry’s most basic principles — the idea that “like dissolves like.”

Published in PNAS, the study suggests these interactions could reshape our understanding of Titan’s geology and help explain how essential molecules — amino acids and nucleic bases — might have formed in such environments. “This could help us better understand prebiotic chemistry and how it develops in extreme conditions,” said study leader Martin Rahm.

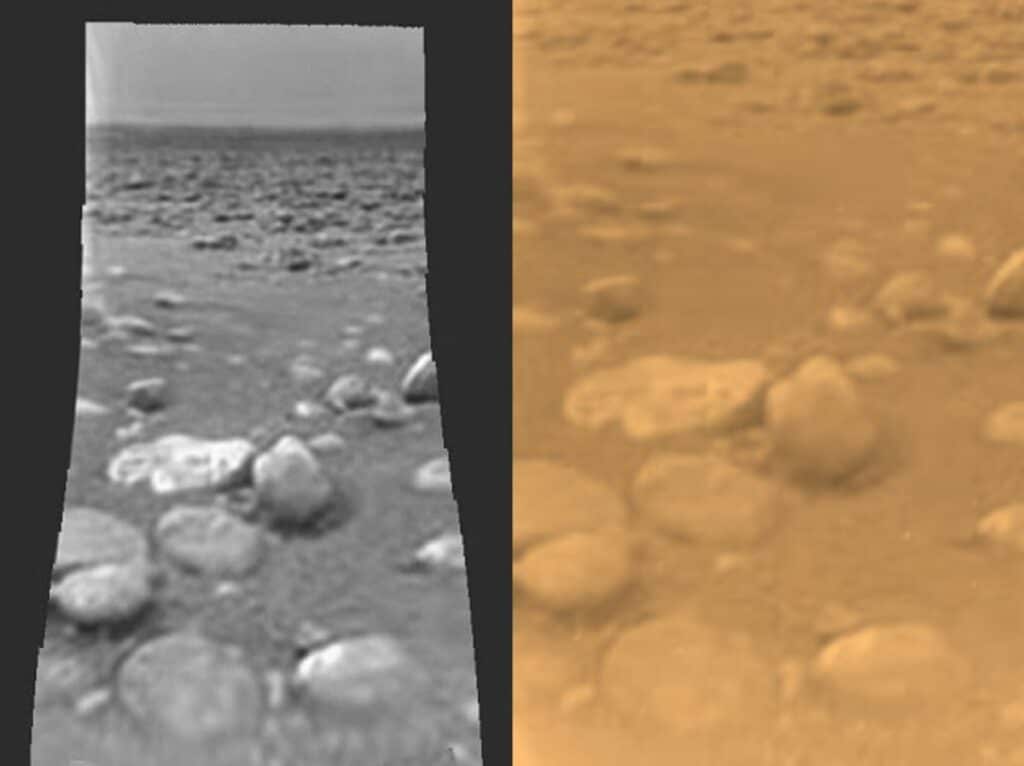

The only image of Titan’s surface, taken by the ESA’s Huygens probe, which landed on this moon of Saturn in January 2005. © ESA

How the team uncovered the co-crystals

To uncover these strange interactions, Rahm’s team used advanced computer simulations alongside laser spectroscopy experiments. Together, these tools revealed that stable crystal structures could exist at extremely low temperatures — conditions that would normally prevent such bonding.

“This is a beautiful example of pushing chemistry’s limits,” said Rahm. “It shows that even long-standing scientific rules aren’t always absolute.”

Beyond Titan’s chemistry, this discovery could help explain the moon’s mysterious landscapes — its lakes, seas, and dunes — and provide clues about how key organic compounds may form naturally. Hydrogen cyanide, in particular, may play a vital role in creating the chemical foundations of life, including amino acids and the molecules that encode genetic information.

What’s next for Titan exploration

NASA’s Dragonfly mission, scheduled to land on Titan in 2034, will study its surface up close. Until then, Rahm and his colleagues plan to continue examining hydrogen cyanide’s unique chemistry, in collaboration with NASA scientists.

“Hydrogen cyanide exists in many environments — from interstellar dust clouds to planetary atmospheres and comets,” Rahm explained. “Our findings could help reveal what happens in other cold regions of space and whether other nonpolar molecules can also form similar crystals — potentially shaping the chemistry that comes before life.”

Expanding the frontiers of science

This discovery is more than just a scientific curiosity — it challenges long-held assumptions and underscores the value of questioning even chemistry’s “unbreakable” rules. It also shows how collaboration between institutions like Chalmers and NASA continues to drive innovation, opening new paths in the study of astrochemistry and the origins of life.

![]()

Rémy Decourt

Journalist

Born shortly after Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon in 1969, my journey into space exploration has been entirely self-taught. A military stay in Mururoa sparked my formal education in space sciences, and early sky-watching experiences in an astronomy club ignited my passion. I founded flashespace.com, transitioning from sky observation to a deep interest in space missions, satellites, and human and robotic exploration. Since 2010, I’ve been part of Futura’s editorial team, covering space news and working as a freelance writer with extensive international field experience in space-related sites.