Clyde Yancy emphasized that, instead, “there is a benefit to lifestyle modification” in AF.

NEW ORLEANS, LA—Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibition does not seem to be a solution to the problem of arrhythmia recurrence after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation (AF), results of the DARE-HF trial indicate.

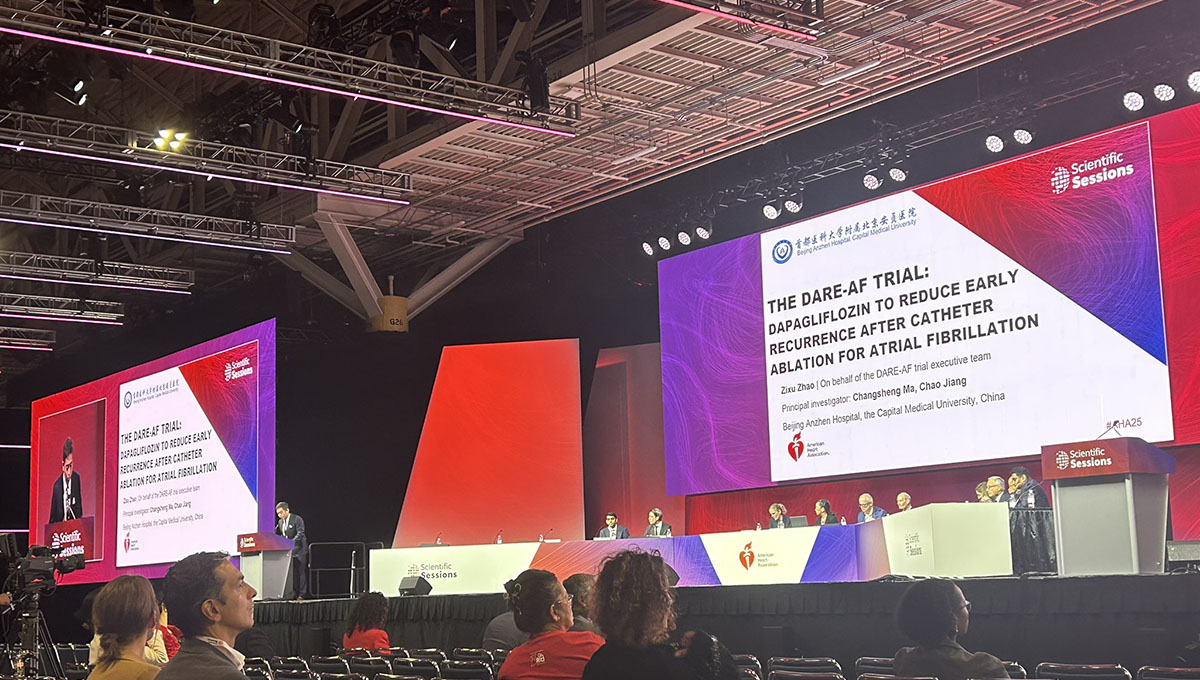

Among patients with persistent AF and no established indication for SGLT2 inhibitors, use of dapagliflozin (Farxiga; AstraZeneca) for 3 months after ablation was no better than usual care for reducing AF burden or arrhythmia recurrence, Zixu Zhao, MD (Beijing Anzhen Hospital, China), reported recently at the American Heart Association 2025 Scientific Sessions.

The results, published simultaneously online in Circulation, “suggest that the potential antiarrhythmic effects of SGLT2 [inhibitors] might stem from the improvement in underlying cardiometabolic conditions, rather than a direct antiarrhythmic effect,” he concluded.

Though catheter ablation has become a first-line therapy for AF, roughly 30% to 40% of patients will have a recurrence after the procedure, Zhao said. There are hints that SGLT2 inhibitors may reduce the risk of AF—in a post hoc analysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial and in registry studies from China, for instance. It could be, Zhao said, that the agents are improving AF through beneficial effects on related comorbidities like heart failure, hypertension, and obesity, which in turn have a positive impact on electrical and structural remodeling of the left atrium.

All prior studies of the effects of SGLT2 inhibition on AF, however, have included patients with diabetes, heart failure, or chronic kidney disease, and there is a lack of randomized evidence to confirm potential benefits in patients without an established indication for the therapies.

The DARE-AF Trial

DARE-AF, conducted at Beijing Anzhen Hospital, included 200 patients (mean age about 58 years; 81% men) who were undergoing first-time catheter ablation for persistent AF and who did not have diabetes, heart failure, or chronic kidney disease. They were randomized within 24 hours of the procedure to dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily plus usual care or usual care alone for 3 months.

The median duration of AF was 1 year, with 29% having had the arrhythmia for more than 12 months. Median CHA2DS2-VASc score was 1. Slightly more than half (52%) had hypertension, and the mean LVEF at baseline was 60%.

Ablation included bilateral pulmonary vein isolation in all patients, with additional ablation used if that failed to restore sinus rhythm; radiofrequency catheters were used in 98% of procedures. All patients were anticoagulated for at least 3 months after ablation.

The majority of patients (72%) were taking antiarrhythmic drugs for the first postprocedural month, with that proportion falling to about 33% in the second month and 10% in the third. Full compliance with the dapagliflozin regimen was reported by 86% of patients, with urine testing for glycosuria positivity confirming good adherence in 90%.

The primary outcome was AF burden at 3 months, measured with a single-lead ECG patch worn for 7 days. AF burden was 7.5% in the dapagliflozin arm and 8.1% in the control arm (P = 0.48). The cumulative incidence of AF recurrence over that span also did not differ between the dapagliflozin and usual-care groups (29.5% vs 28.0%; HR 1.11; 95% CI 0.66-1.86).

Left atrial diameter decreased to a similar extent in the intervention and control arms (mean -4.9 vs -4.7 mm; P = 0.87). Improvements in scores on the AF Effect On Quality-Of-Life Questionnaire (AFEQT) through 3 months did not differ between groups (mean -29.6 vs -28.2 points, P = 0.68).

The use of dapagliflozin was safe in this scenario, with no difference in the rate of serious adverse events compared with usual care (11% vs 10%). There were two deaths, both in the dapagliflozin group, but they were deemed unrelated to study treatment; one was due to an MI and the other cardiac arrest. Dapagliflozin was associated with one case of hypotension and one urinary tract or genital infection.

Zhao pointed to some limitations of the analysis, including the open-label design, which leaves it vulnerable to bias; the short treatment duration; the use of an ECG patch rather than an implantable loop recorder to assess AF recurrence; and the inclusion of an all-Chinese population, which limits generalizability.

Discussing the results after Zhao’s presentation, Clyde Yancy, MD (Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL), said DARE-HF shows that SGLT2 inhibition does not reduce arrhythmia recurrence after AF ablation in this specific population.

“But we do know . . . that there are proven strategies,” he said, showing a slide listing measures like blood pressure control, weight loss of greater than 10%, glycemic control, management of obstructive sleep apnea, and exercise. He also pointed to the results of the ARREST-AF trial, “which gives us an evidence base to suggest that without question, there is a benefit to lifestyle modification on the important condition of atrial fibrillation.”

Yancy concluded that lifestyle modification works not only for AF, but also “probably for every other cardiovascular disease condition.”