Contemporary history is relentless both in its pace and in its ramifying entanglements. It challenges us both to grasp the reality unfolding around us and to constantly define and redefine our position in relation to it. China’s dramatically expanding footprint in the world economy is a case in point. How is it changing the world and how do different observers (in the West in this case) relate to it?

The sheer pace and scale of China’s development has its own politics. One might say that this is the politics of an overwhelming, headlong, momentum-driven “breakneck” rush. Standing back, doing the timelines and setting the scene, above all in terms of the macroeconomics, is a way both of orientating oneself and gaining perspective.

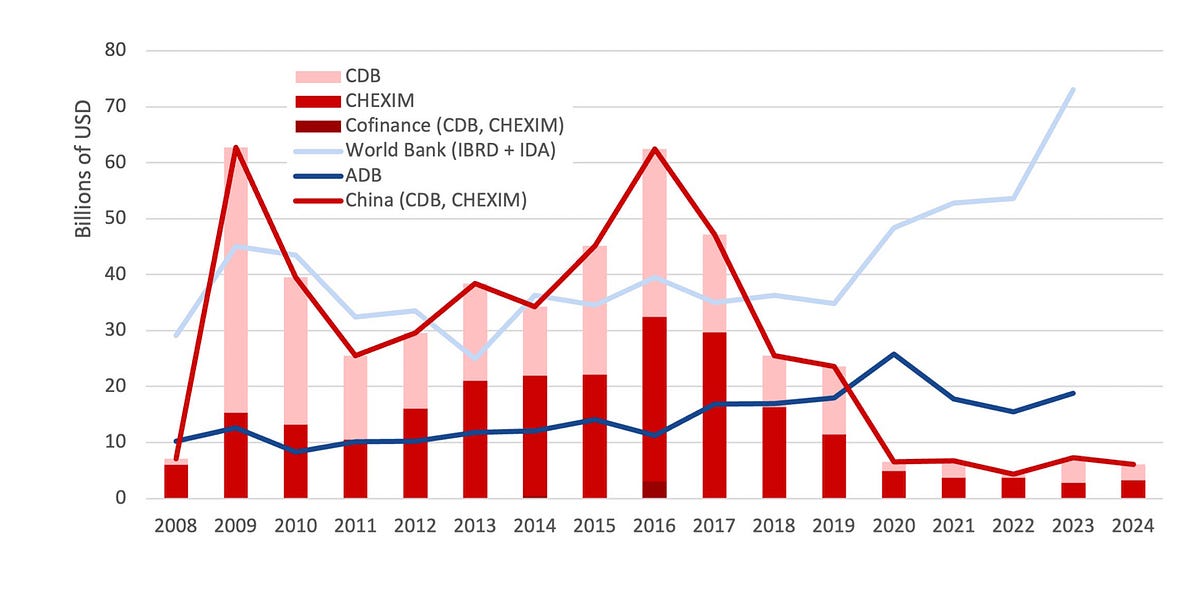

In the 2010s, the world woke up to the reality of China as a driving force in global development under the sign of One Belt One Road (BRI). In 2015-2017 China’s two major development banks were lending more than the World Bank, the world’s leading concessional lender.

Source: BU

Then came a sudden slowdown in 2018 followed by a crunch in 2020. Even before we had really begun to grasp what BRI was about, we had to adjust to the fact that China was no longer lending and was now caught up as a creditor in a series of national debt crises.

And now, before either of those previous phases have been fully digested or fully born fruit, we read headlines announcing that we are entering a third phase. Call it BRI 2.0, or a Green Leap Outward.

As reported by the Economist, Christoph Nedopil of Griffith University in Australia, working with the Green Finance and Development Centre at Fudan University in Shanghai has compiled remarkable data on the latest phase of BRI commitments, which show a major surge since 2022 and a new peak of commitments in H1 2025.

Meanwhile, the Net Zero Policy Lab’s data show a huge surge in green manufacturing FDI since 2022.

It would be GREAT to have the two teams from Hopkins/Boston and Griffith/Fudan confer to see if and how their data sets overlap.

But even more important is to place the latest headlines about green FDI and new BRI projects in the context both of the earlier history of lending and its ramifications and the broader and highly complex political economy of China’s trade and financial relationships with the world.

As for chronology and legacies, a recent report by the GLOBAL CHINA INITIATIVE of Boston University’ Global Development Policy Center by REBECCA RAY, KEVIN P. GALLAGHER, ZHENG ZHAI, MARINA ZUCKER-MARQUES AND YAN LIANG provides an important corrective.

The huge pile of lending by China in the 2010s results in a large pile of debt. As the Boston team report:

Between 2008 and 2024, China’s two globally active development finance institutions (DFIs)—the China Development Bank (CDB) and the ExportImport Bank of China (CHEXIM)—committed more than $472 billion to countries in the Global South (Ray et al. 2025).

Even if this was on the whole at relatively generous terms (c. 4%), when payment comes due the reverse flow of income to China is substantial.

And since this occurred at the same time as new lending falls to low levels, the net result is that China has become a recipient of net payments from low-income countries rather than a source of development finance.

Earlier in the year the Lowy Institute published this striking graph showing the twin peaks of new loans and loan repayments from low-income and vulnerable countries.

Source: Lowy Institute

This reversal of flows is by no means unique to China. The reversal for private bond market lending to developing countries is even more dramatic.

But the squeeze is real and it is particularly acute for the poorest countries – those that are IDA eligible.

The pièce de résistance of the Boston University report is a table showing the role of China along with other major creditors in applying the squeeze to poor developing countries. The countries in the top panel are those where it is China’s loans that are applying the most pressure.

Just to be able to wrap our heads around the variety of incoming signals, it would be fantastic to reconcile the BU story about a financing crunch with the data from Griffith and Fudan on a new wave of BRI commitments and the green energy investment data from the Hopkins Net Zero Policy Lab, on largely private sector investment in green manufacturing. Are the old debts and the new commitments in the same places or not? Who are the creditors and debtors in each case?

And then there are the broader macroeconomics and political economy.

I started this morning reading the BU report thinking about the insufficiency of concessional lending to poor countries. Two hours later I was scrambling around amongst the many issues on the “great wall of China worries”.

Soon I found myself catching up with Brad Setser, the Western master of China’s balance of payments statistics. How does the surge in Chinese foreign lending relate to the overall situation of a surging current account surplus? How is the capital outflow regulated? Where do BRI investments, concessional lending, Fx reserves, Treasury holdings, gold accumulation sit on the national balance sheet?

How much is the export surplus an effect of macroeconomic demand imbalance? How much is that a matter of Chinese policy? How much does the surplus reflect imbalances in the importing countries? On these questions the IMF takes a notably “dovish” view, stressing multipolar imbalances rather than Chinese exceptionalism and industrial policies.

What is clear is that China’s historic export surge is exerting pressure around the world and that in turn has to be connected back to the both the economics and politics of investment.

As the Economist (Simon Rabinovitch?) remarks, the new surge of BRI investment can be interpreted as a comprehensive policy of stabilization on Beijing’s part.

Xi Jinping, sees difficult times ahead. At a conclave of the Communist Party’s most senior officials that ended on October 23rd he warned that over the next five years the task of ensuring China’s development while maintaining its security would become “much harder” amid a “notable rise in uncertainties and unforeseen factors”. … The cure for Trumpian instability, as he sees it, is an alternative order that draws the rest of the world a lot closer into China’s orbit. Enter the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). … Many BRI countries are seeing their trade deficits with China widen. Protectionist mutterings are growing louder in both Africa and South-East Asia. … Yet China knows these countries are a captive audience. Some may quietly grumble about trade imbalances or debt, but the technology and building skills offered by China are hard to find elsewhere. China hopes such countries see little choice other than to support it in its desire to be the architect of an alternative world order. As a Communist Party journal recently put it, the BRI will help create “a new paradigm of global governance”. In a Trump-troubled world, Mr Xi sees opportunities still.

In this narrative, BRI creates lock-in. Countries that receive Chinese infrastructure are less likely to push back hard on trade for fear of losing the benefits of Chinese know-how. But the flow of influence can also run the other way, as the Berlin-based think tank MERICS concluded in a report last year, in which it studied the policy reaction of Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Mexico, Turkey, Brazil, and South Africa to China’s massive trade surpluses. MERICS found that China was in fact willing to give ground on domestic content rules, investments requirements etc, precisely so as to keep the geopolitical game open.

Beijing tolerates economic losses where it can make political advances, but swings hard against countries it has politically written off … Our survey has shown that the EU is far from alone in facing the need to respond to potential harms from a surge in Chinese exports that benefit from extensive hidden subsidies. However, from the Chinese party-state’s perspective, trade with many countries is viewed as a tool to achieve political goals. Beijing leverages its economic statecraft through massive state-led foreign investment schemes, such as the BRI, and its large domestic market for foreign imports. This enables China to use the market shares of Chinese goods in other countries in exchange for prioritizing political identity and alignment. Among the eight selected countries (), all except Mexico and Brazil are signatories of the BRI. With the exception of Turkey, all are comprehensive strategic partners of China, and all except Mexico have joined the AIIB. Moreover, all but Vietnam have Huawei’s presence in their 5G networks. All these alignments indicate certain political foundations with China that justify China yielding on points of friction in the economic relationship. When comparing China’s responses to trade restrictions, a clear trend emerges: Chinese policymakers prioritize political gains over economic interests where they see potential geopolitical wins. As a result, despite trade restrictions on Chinese goods from developing countries and the Global South, China has mostly refrained from retaliatory measures. In contrast, China’s response to countries that Beijing feels it cannot win over politically (or which have named China as a rival) is much sharper – such as the threats after the EU’s tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles were imposed, or previously in its trade war with the US and cases of economic coercion against Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Canada, and others.

In the Economist rendering it is the Global South recipients that absorb China’s capital flow and exports, so as not to lose the benefits of BRI. Beijing knows this and thus promotes BRI lending so as to expand the reach of its new global order. MERICS shows us the other side of the coin. In the important group of EM it has studied, it finds Beijing tolerating pushback to China’s trade surpluses precisely in those cases where Beijing judges that there may still be something to play for in geopolitical terms. Rather than plumping for one or the other reading, the task is clearly to think through this uneven-and-combined back-and-forth. In the spirit of Chartbook 461 this is the stuff not of instituting a clearly defined new order but of doing the work of ordering.