Scientists in Toronto have unveiled a chilling breakthrough, a laser-regulated atomic clock cooled to just five degrees above absolute zero, promising a leap in timekeeping accuracy unlike anything used today.

Physicists at the University of Toronto have developed the world’s first cryogenic single-ion optical atomic clock, a next-generation instrument that could be 100 times more accurate than the clocks currently used to define the length of a second.

The advance marks a major step toward replacing the legacy cesium clocks that have anchored global timekeeping for decades.

The new device could refine the foundation upon which physics, navigation, telecommunications, and countless precision measurements depend.

“Accurate measurements of time and frequency underlie our entire system of physical units,” said Professor Amar Vutha.

“Therefore, improving the accuracy of timekeeping devices leads to stronger foundations for every physical measurement.”

Freezing out noise

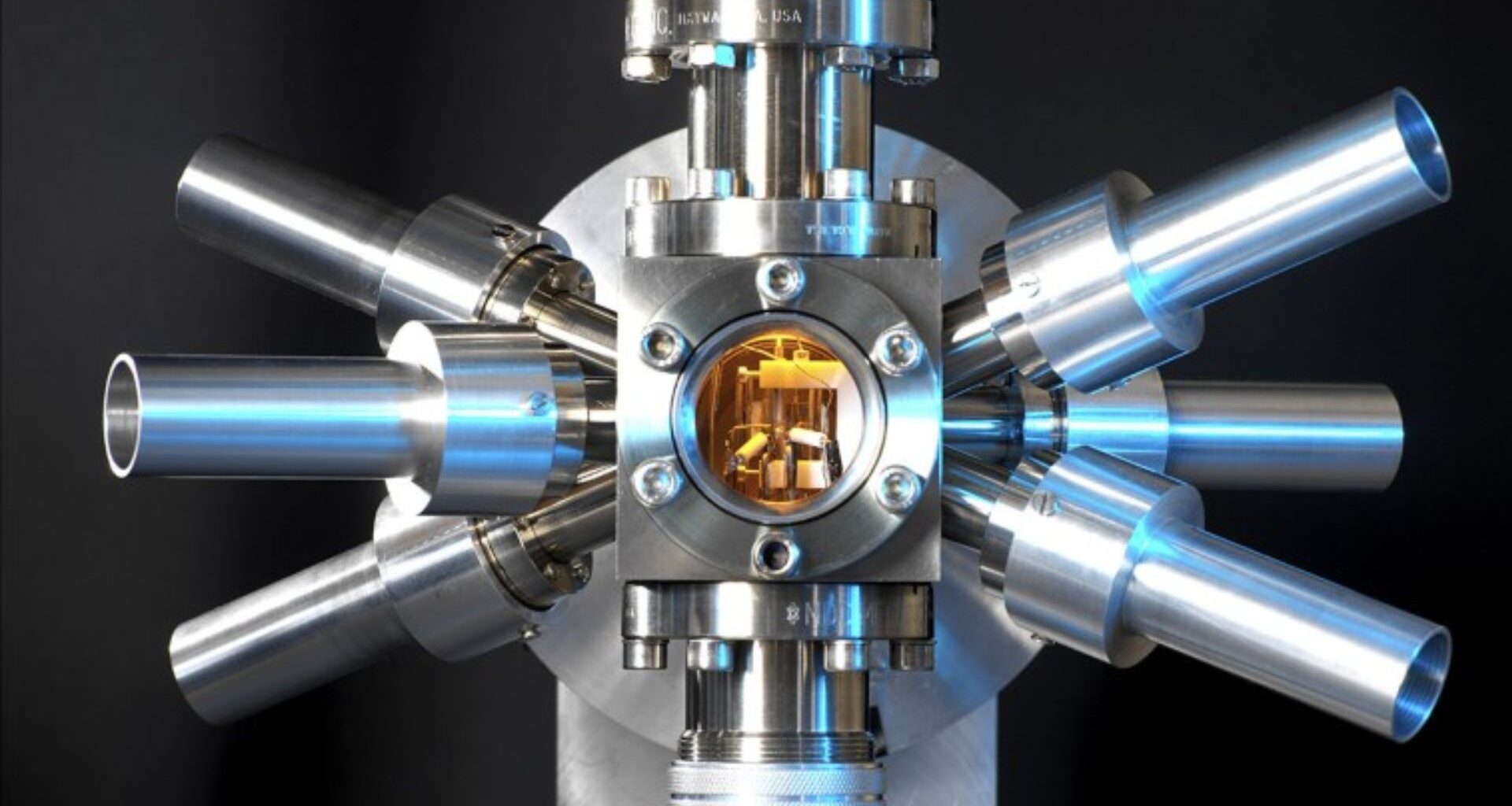

Vutha, an experimental physicist in the Department of Physics, and PhD researcher Takahiro Tow built on previous work in their lab to create a device that stabilizes an optical laser using a single trapped strontium atom.

All clocks, from pendulums to quartz watches to atomic clocks, rely on a stable repeating event. “In every good clock, the periodic event must be stable,” Vutha said. “It wouldn’t do for it to run faster occasionally and then slower.”

In atomic clocks, the “tick” comes from the electromagnetic oscillations of a laser. “The stable periodicity of the laser is ensured by an atom; the quantum vibrations of the atom work like a tuning fork to keep the laser ‘in tune,’” he explained.

Earlier generations of atomic clocks used microwaves and later visible-light lasers, with each jump improving frequency stability by orders of magnitude.

Today’s state-of-the-art optical clocks offer accuracy to 18 decimal places, which is roughly equivalent to measuring the distance from Earth to the Moon to one-millionth of a millimeter.

Cooling the tuning fork

Yet even these extraordinary devices face a common limitation: heat. Atoms used to regulate optical clocks are perturbed by infrared radiation emitted by surrounding components, including the metal vacuum chamber holding them.

“The regulating atoms in current optical atomic clocks are still perturbed by infrared light — heat — emitted by nearby objects,” Vutha said. “This limits their accuracy because, if the tuning fork itself goes out of tune, then you no longer have a stable clock.”

The Toronto team’s breakthrough was chilling the trapped strontium atom to below five Kelvin, dramatically reducing thermal radiation and eliminating a core source of frequency drift.

This cryogenic environment allows the atom to maintain its “tuning fork” role with far higher stability.

Time’s deeper meaning

Ultra-precise timekeeping has cascading scientific consequences. Basic electrical standards, such as the ampere and volt, rely on exquisitely accurate time and frequency measurements.

“The definition of the standard of current — the ampere — requires measuring the number of electrons that flow… within an accurately calibrated time interval,” Vutha noted.

But the most profound use of ultra-accurate clocks may be in testing nature’s deepest assumptions.

“The most successful application of the new generation of optical clocks has been to test whether the fundamental constants of nature… are themselves constant,” Vutha said.

This includes the speed of light and Planck’s constant. “There’s just no other way of doing these kinds of experiments than with atomic clocks.”