Scientists have traced the origins of the most massive black hole merger ever observed, revealing how two “impossible” giants may have formed despite long-standing assumptions that such objects should not exist.

These black holes were considered “forbidden” because stars of that size were thought to blow themselves apart in extremely powerful explosions, leaving behind no remnant that could collapse into a black hole.

You may like

The findings also suggest that black holes can form more efficiently than scientists thought, which could transform our understanding of how the universe’s first stars and black holes gave rise to today’s supermassive black holes.

Why heavy black hole mergers matter

Black hole collisions have become one of the most important tools for understanding the universe.

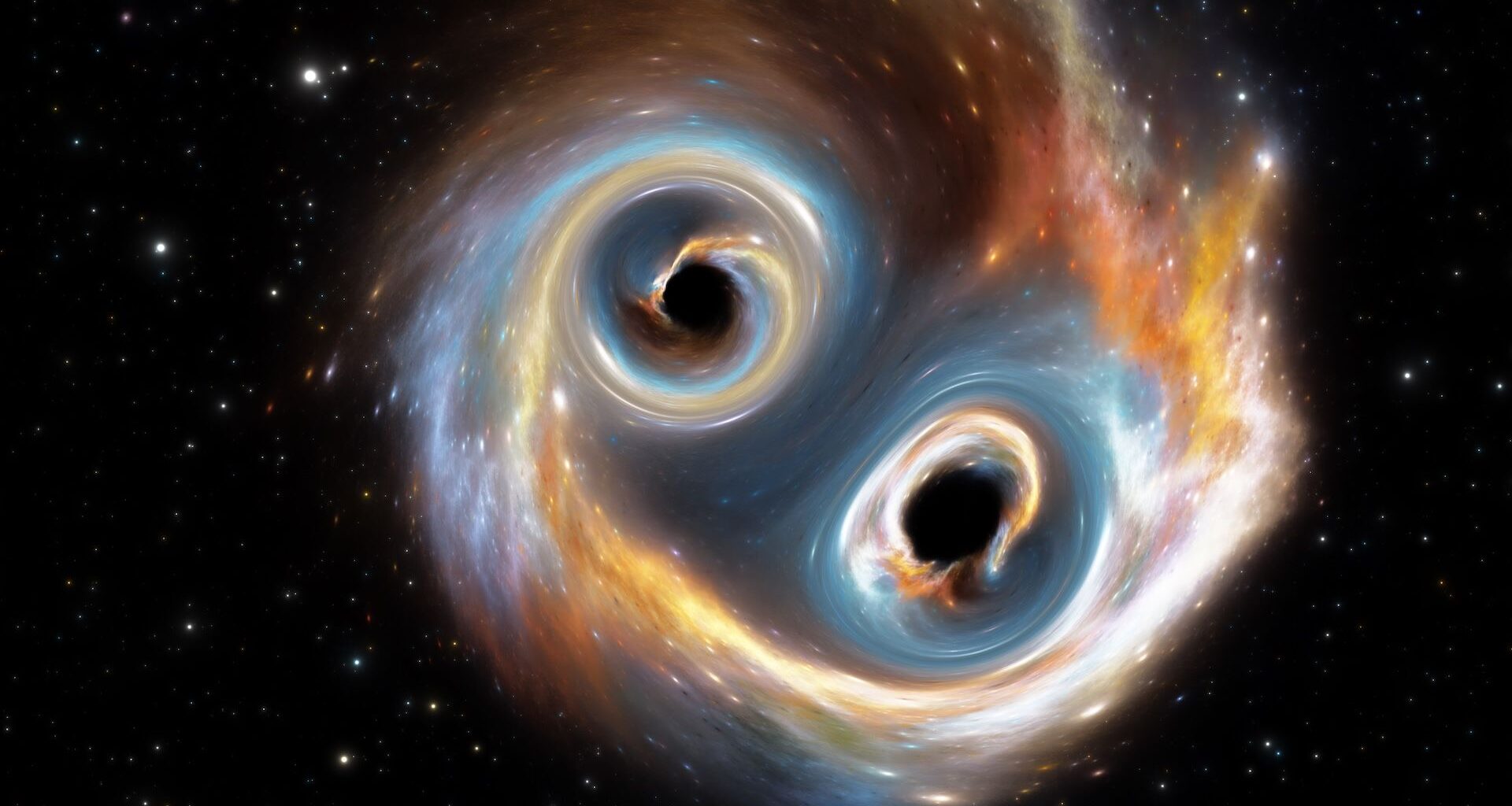

“Black hole mergers allow us to observe the universe not through light, but through gravity — via gravitational waves produced by the distortion of space and time as black holes spiral together and merge,” Ore Gottlieb, a professor at the Center for Computational Astrophysics who led the work, told Live Science in an email. Gravitational waves offer a rare view into regions of space where gravity is so extreme that not even light can escape. From the shape of the signal alone, scientists can infer the masses and spins of the merging objects and reconstruct how they formed.

These observations test Einstein’s theory of general relativity where its predictions are the most demanding, because the space-time curvature around merging black holes pushes the theory to its limits. Events involving the heaviest black holes also reveal how massive stars lived and died across cosmic time and how early black holes grew into the monsters that sit at the centers of galaxies today.

The most massive black hole merger ever detected

When detectors recorded GW231123 in November 2023, astronomers quickly realized it stood apart. Two enormous objects — roughly 100 and 130 times the mass of the sun — had merged more than 2 billion light-years away. The surprise was that black holes of this size fall into what physicists call the “mass gap,” a range between roughly 70 and 140 solar masses where no black holes were expected.

Stars in this range usually tear themselves apart through violent supernova explosions, leaving nothing behind. Yet GW231123 housed not one, but two such objects — and both showed signs of spinning at extreme rates. The event involved “two of the most rapidly spinning black holes, indicating a rare formation channel of massive and rapidly spinning black holes, which were not supposed to exist,” Gottlieb said.

To unravel how such black holes could form, the team created detailed, three-dimensional simulations, starting from the life of an extremely massive star. The model followed a helium core about 250 times the mass of the sun as it burned fuel, collapsed, and formed a newborn black hole. Earlier theories assumed such a star would collapse in one piece, leaving a black hole as heavy as the original core. But the new study shows this is not always the case.

You may like

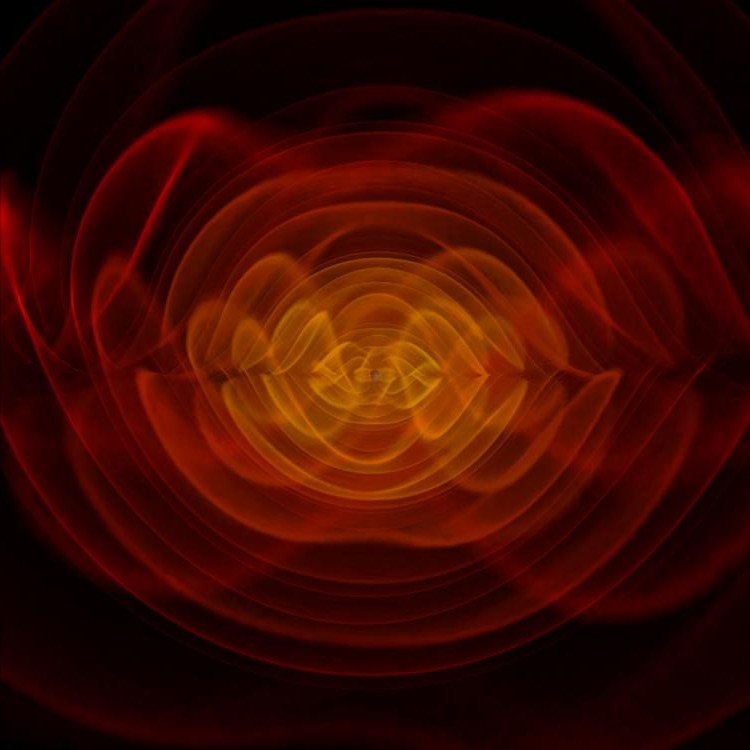

An illustration of what gravitational waves from a black hole merger would look like, if humans could see them. (Image credit: NASA/C. Henze)Solving the impossible

Gottlieb and colleagues found that rapid rotation changes everything.

“We showed that if the star rotates rapidly, it forms an accretion disk around the newly born black hole,” Gottlieb explained. “Strong magnetic fields generated within this disk can drive powerful outflows that expel part of the stellar material, preventing it from falling into the black hole.” Instead of swallowing the entire core, the young black hole loses access to much of the surrounding matter as magnetic forces blast material into space.

This mechanism reduces the final mass of the remnant, pushing it down into the mass gap — a region previously thought unreachable. “As a result, the final black hole mass can be significantly reduced, landing within the mass gap, a range previously thought to be inaccessible,” Gottlieb said.

The simulations also naturally produced a link between the mass and spin of the resulting black hole. Strong magnetic fields extract angular momentum, thus slowing the black hole while ejecting more mass. Weaker fields leave a more massive, faster-spinning object. This relationship closely matches the properties inferred for the two black holes in GW231123. One would form in a star with moderate magnetic fields, and the other would form in a star with weaker ones, creating a pair with different final masses and spins — exactly what the gravitational wave signal suggests.

What these discoveries mean for gravity and cosmic history

Extreme events like GW231123 stretch general relativity to its breaking point.

“The tremendous curvature of space and time probes general relativity deep in its most extreme strong field regime, enabling us to test whether Einstein’s equations remain accurate when gravity is at its most extreme,” Gottlieb noted.

If similar events happened frequently in the early universe, they would have shaped the growth of the first black holes. Such mergers “imply that massive black holes can form more efficiently than current stellar models predict,” Gottlieb said. “This would affect our understanding of how the first generation of stars and black holes seeded the supermassive black holes we observe in galaxies today.”

The team’s work points to a new formation pathway for massive black holes and predicts specific patterns astronomers can search for. “Our work opens a new window to black hole formation within the mass gap, predicting first-generation black holes (without previous mergers) at all masses,” Gottlieb said. Future gravitational-wave detections will test whether the mass-spin correlation found in the simulations holds across many events.

“As we detect more massive black hole binaries, we will be able to test the predicted correlation on this population,” Gottlieb said. These discoveries may reveal whether GW231123 is a cosmic rarity or the first clear sign of a hidden population of massive, rapidly spinning black holes.