Scientists at Texas A&M University say they may have found a way to stop or even reverse the decline of cellular energy production.

Their approach uses engineered particles to push stem cells into producing extra mitochondria, which then move into weakened cells and restore lost energy.

The work could influence treatments for aging, heart disease, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Researchers linked many age-related and degenerative conditions to declining mitochondria.

As cells grow older or suffer chemical or disease-induced injury, they lose the tiny structures that power their functions. Once that decline accelerates, cell health drops sharply.

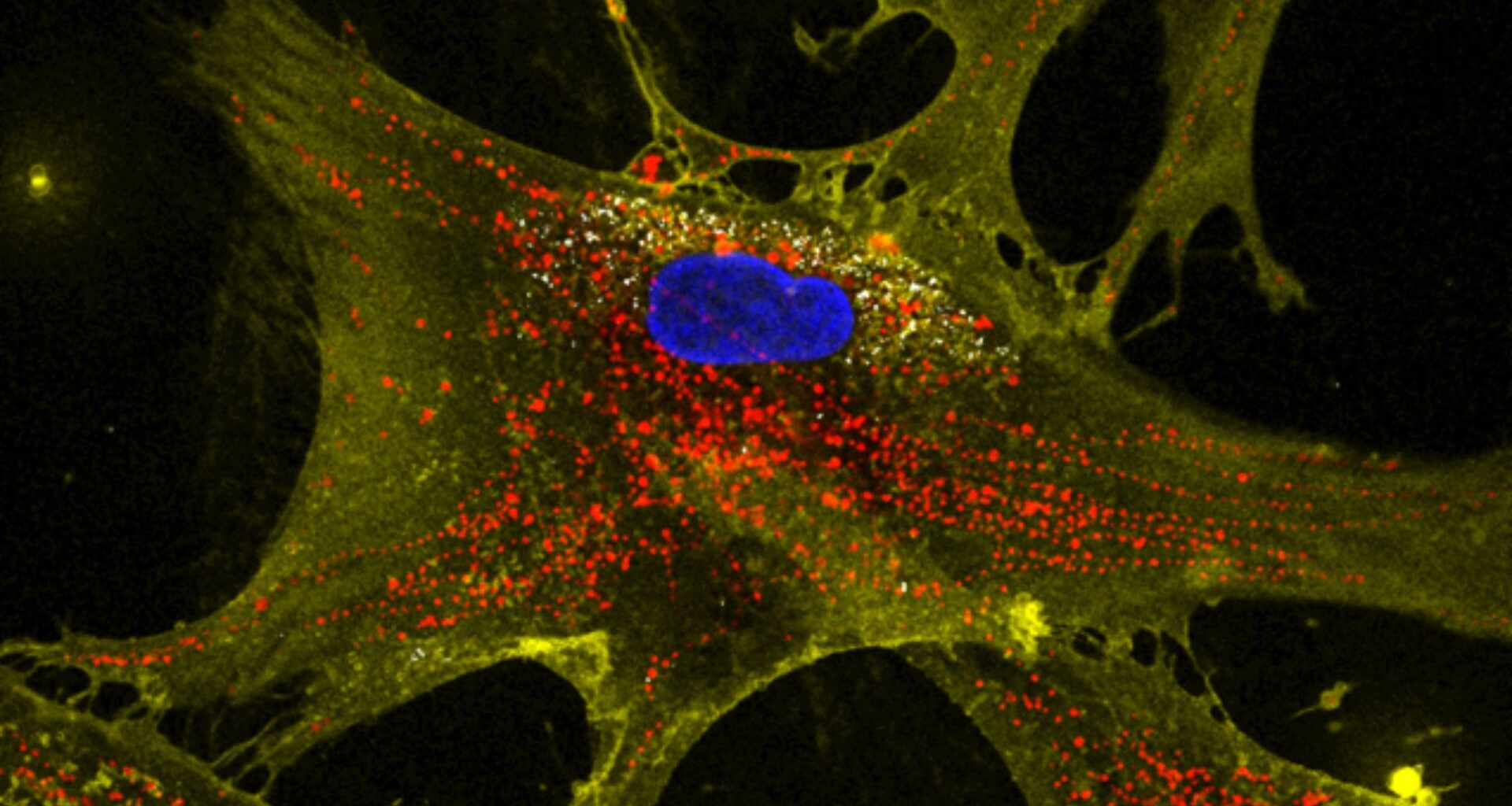

The team tested a method to counter that loss. They created microscopic flower-like particles, or nanoflowers, made of molybdenum disulfide.

When stem cells encountered these particles, they produced roughly twice their usual number of mitochondria. These boosted stem cells then transferred the surplus to impaired cells.

Dr. Akhilesh K. Gaharwar, a professor of biomedical engineering, said the approach trains healthy cells to support weaker ones. “We have trained healthy cells to share their spare batteries with weaker ones,” he said.

He added that increasing mitochondria inside donor cells helps damaged cells regain function without the need for drugs or genetic changes.

Boosted cells show strong recovery

The upgraded stem cells transferred two to four times more mitochondria than untreated ones.

Damaged cells absorbed these mitochondria and regained energy output. They also showed improved resistance to stress.

Exposed cells survived chemotherapy-like insults that normally cause a rapid decline.

Lead author John Soukar compared the effect to swapping out a failing power source.

“It’s like giving an old electronic a new battery pack,” he said.

He explained that instead of discarding weakened cells, the method lets researchers “plug” charged mitochondria from strong cells into struggling ones.

Existing methods to increase mitochondria rely on small-molecule drugs that clear quickly from cells.

The Texas A&M technique uses larger nanoparticles that stay inside stem cells longer and continue to trigger mitochondrial production.

Soukar said early data suggests possible monthly dosing rather than frequent treatments.

Gaharwar called the work an early but promising step. “This is an early but exciting step toward recharging aging tissues using their own biological machinery,” he said.

He noted that safely boosting this natural sharing system could help slow or even reverse some aging effects.

Broad therapeutic potential

Researchers say the method could work across many tissues. Stem cells already play a central role in regenerative medicine.

Enhancing them with nanoflowers could expand their capabilities.

Soukar said the approach offers flexibility. “You could put the cells anywhere in the patient,” he said.

He explained that teams could target the heart in cardiomyopathy or inject directly into the muscle for muscular dystrophy.

He said the work could lead to new treatments for diseases for years.