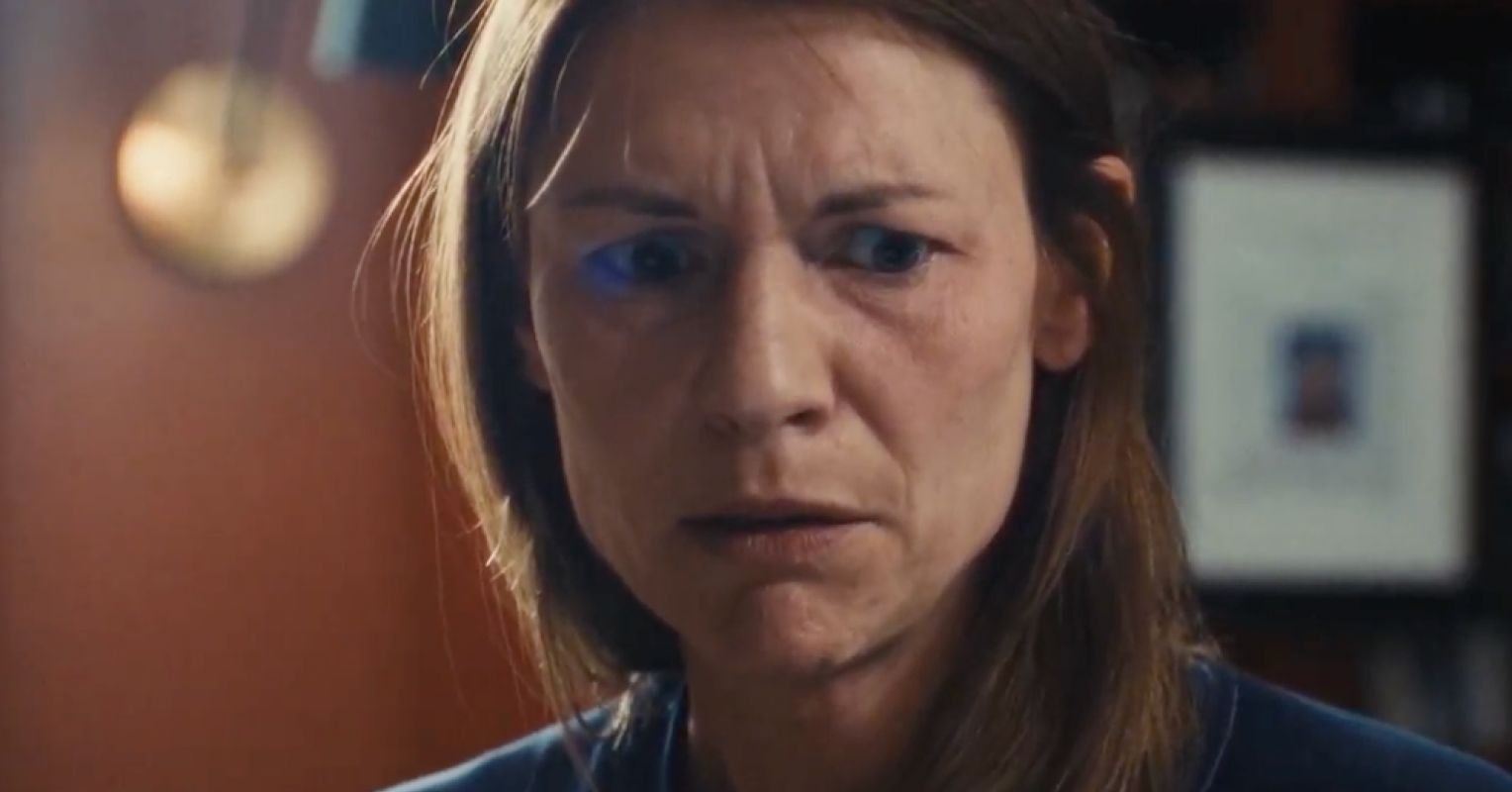

Claire Danes’ acting chops have been on full display since her star teenage turn in My So-Called Life. Now that she is 46 and starring in a new Netflix show, The Beast in Me—no spoilers; don’t worry, I have two episodes to go myself—her ability to showcase subtle, complex, and rapidly shifting emotions remains impressive. Why is this surprising or noteworthy, you may ask? She is an actor, after all. When so many female actors her age and younger have turned to fillers and surgery to maintain a youthful look, and when make-up companies literally market skin care to 4-year-olds (I wish I were exaggerating), I never take for granted the rare female on screen who basically looks their age—with much gratitude to the late great Diane Keaton. It has become the norm in Hollywood and beyond for younger and younger women to respond to the ongoing pressure to maintain timeless youth and beauty by artificially reconfiguring their faces [I have written on the perils of youth-beauty culture time and again].

Danes’ character in The Beast in Me “reads” as a 40-something complex and compelling person whose face not only provides a beacon for aging naturally but remains a versatile canvas on which to display a host of emotional experiences such as empathy, fear, hope, agitation, and elation. (Her co-star, Matthew Rhys, also appears to be aging naturally, although this is less notable as male actors are under less pressure to maintain a flawless, youthful appearance.)

Some of Danes’s look is no doubt due to the particular character she is playing—that of a gay, best-selling author in the aftermath of a traumatic loss and divorce who seems to have no interest or patience for make-up or form-fitting clothes (perhaps leaning in to stereotypes that gay women are not concerned about their appearance, although her ex-wife is portrayed as bohemian chic). The character’s natural style, which includes dark brown hair, is also seemingly associated with her gravitas; she acts as a foil for the wife of the male protagonist, who embodies more traditional beauty ideals (i.e., white, slim, blonde, and made-up). All this specific symbolic signifying aside, the show has achieved mainstream success—and, at least anecdotally, others, from entertainment outlets to reddit users, have also expressed their appreciation. I have found myself embracing the aged reality of my own 50-year-old face after viewing!

Being able to use our faces to reflect our inner states is not merely a tool for brilliant acting; it also enables us to experience and convey our emotions more fully. According to the facial feedback hypothesis, we gain some emotional insight from our own facial expressions; i.e., we feel happy in part because we sense ourselves smiling, or angry in response to a scowl. Moreover, when we authentically communicate our “true self” to others, barring toxic behavior, we are better able to form and maintain positive social bonds. When we feel seen for who we truly are and can form relationships on that basis, we can seek solace from others when needed, and share joy. Just as importantly, the ability to express emotions has the added (original?) benefit of helping us empathize with others. Turns out, facial feedback, premised on facial mimicry, is implicated in the ability to accurately interpret other people’s emotional lives.

When we are affiliating with others, we have an automatic, evolutionarily-derived tendency to mimic their emotional and physical expressions (non-conscious mimicry), which in turn facilitates feelings of interpersonal closeness. Why? Reflecting others’ emotional expressions signifies empathy—we are seeing the world from their perspective and validating their experiences. This begs the question, what happens if our faces are somehow unable, because of volitional cosmetic intervention or random genetic circumstance, to convey emotional states? It turns out that the ability to accurately interpret others’ emotions is impaired when the ability to manipulate our facial features is impaired, whether due to a Botox injection (vs. a control filler without paralytic properties) or because we experience facial paralysis for natural reasons. Further, preliminary research suggests that being injected with Botox, relative to a control substance, dampens emotional responses to positive and negative themed television clips.

Back to Claire Danes. Not only does her face showcase the performance-enhancing benefits of being able to wrinkle her forehead quizzically when the moment demands, but she is a reminder for viewers of all ages and genders that a female actor does not have to look like a teenager to be valuable and charismatic on-screen (or on the red carpet). Perhaps with this in mind, we can revel in the “crow’s feet” wrinkles around our eyes; they are, after all, emblematic of decades of rich emotional life. Beyond this, however, Danes can remind us that there are myriad social and emotional benefits to using our faces as expressive portals—whether to share our own moods or to empathize and affiliate with others. In a time that’s rife with technological and geopolitical uncertainty and polarization, we would do well to embrace those basic evolutionary bonds that enable cooperation and connection.