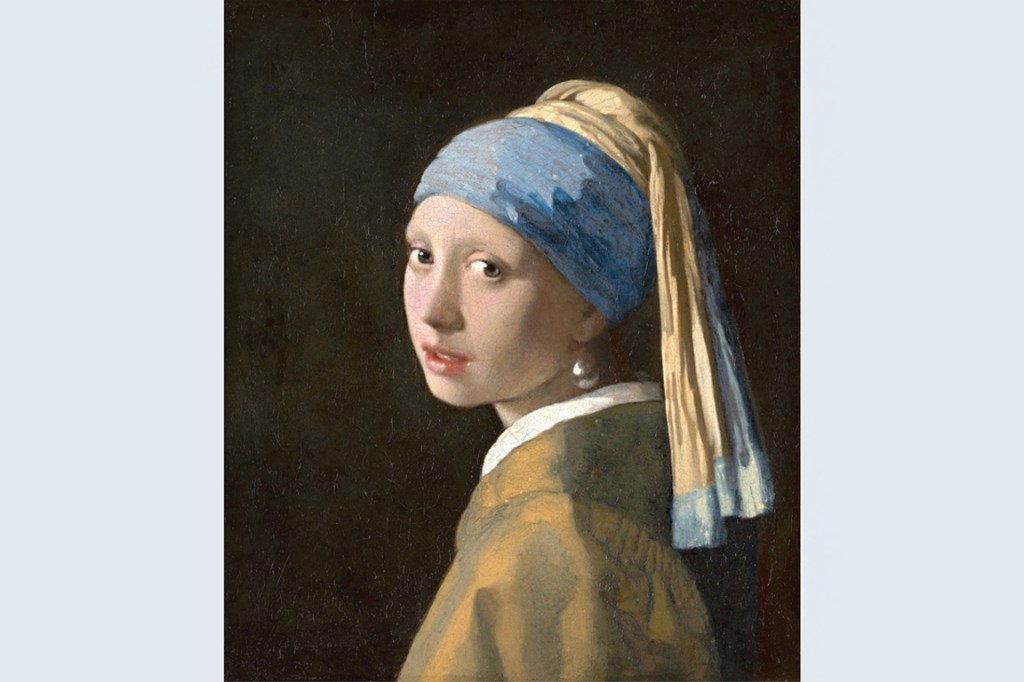

Everybody loves a good mystery. That may explain why, for generations, art lovers have sought to learn the identity of the unknown subject in Johannes Vermeer’s masterpiece, Girl with a Pearl Earring (1665–67). Her ineffable pose (looking back at us over her shoulder), titular bauble, and exotic headgear (the blue turban wrapping her head) have prompted questions for which there are no answers.

That hasn’t stopped people from speculating, however, with endless treatises on the topic and at least one novel adapted into a 2003 film. In the movie, Scarlett Johansson plays a servant in the Vermeer household, the type considered most likely to have posed for him. Competing theories posit that the model was the artist’s daughter, Maria, who was thought to have been his assistant, and moreover the actual author of paintings attributed to her father, such as Girl with the Red Hat (c. 1669) and Girl with a Flute (c. 1669/1675).

Related Articles

None of that is relevant, however, since Girl with a Pearl Earring isn’t a portrait but rather a formal rendering of facial features and expressions known in 17th-century Dutch art as a tronie. These were essentially anonymous head shots serving as still life objects, no different from a bowl of fruit or bouquet of flowers.

Of course, Girl with a Pearl Earring transcends mere study. The luminous work is the best-known example of Vermeer’s limited output, which numbers 34 paintings that we know of, though he may have created up to 50. Vermeer (1632–1675) usually worked small, and Girl with a Pearl Earring itself measures a modest 18¼ by 15¼ inches. These two factors—the intimacy of his canvases and their rarity—have burnished his legend, though this wasn’t always the case.

While Vermeer was respected in his time and earned considerable success, after his death he was all but forgotten for 200 years. This was probably because his reputation was confined to his hometown of Delft. Also, during his later years, an economic downturn occasioned by Louis XIV’s invasion of the Netherlands in 1672 effectively dried up the market for Vermeer’s paintings and for those by other artists that he sold in an art-dealing business inherited from his father. Vermeer had to borrow money to stay afloat, and the resulting financial duress likely contributed to his untimely death at age 43.

Subsequently he was left out of historical accounts of Dutch art, and his paintings were often attributed to other artists. It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that his work was rediscovered, beginning its ascent to the iconic status it enjoys today.

Vermeer was born into a family of entrepreneurs. His grandfather had been a metalworker with a sideline in counterfeiting, and his father was originally a purveyor of silk. Though he was Protestant, Vermeer married a wealthy Catholic woman, converting to Catholicism to allay his mother-in-law’s disapproval of the union. His embrace of the Church was genuine, however, and he extolled its teachings in his painting The Allegory of Faith (1670–1672).

In 1653 Vermeer joined a trade association for painters, which spoke to the economics of art during Holland’s Golden Age. Sales depended on merchant-class patrons who preferred still lifes, landscapes, portraits, and interiors as reflections of their own fortunes. Their aims stood in sharp contrast to the theological and monarchical goals of the pontiffs and potentates who commissioned paintings elsewhere in Europe. Vermeer’s main supporter, for instance, was a brewery heir named Pieter van Ruijven, who, along with his wife, Maria de Knuijt, kept him in business.

Little is known about how Vermeer learned his craft. Some argue that he apprenticed with another artist; others say he was largely self-taught, taking inspiration from two schools of Dutch painters: one from Leiden known for highly detailed naturalism, and another consisting of followers of Caravaggio from Utrecht. Aspects of both were reflected in his practice.

By the mid 1650s, Vermeer had embarked on the earliest of his extant compositions. Among them, a depiction of a prostitute being solicitated by a cavalier (The Procuress, 1656) features a leering man on the left who is believed to be Vermeer himself. (This cameo, and a view of his back in his composition The Art of Painting,1666–1668, are the only self-portraits to survive.) Despite the ill repute of the woman in The Procuress, she’s treated sympathetically. Indeed, women were pictured constantly in Vermeer’s work not as objects of desire but as characters with agency.

Crucial to the understanding of Girl with a Pearl Earring is the way it turns the tables on the male gaze: Limned against a dark, uninterrupted background, she’s the one doing the staring. Her glossy lips are parted slightly to reveal her teeth and perhaps an ever-so-slight glimpse of her tongue, making it appear as if she’s balanced on a knife’s edge between provocation and vulnerability.

But the center of attention remains the gleaming ornament dangling from her ear. Pearls appear regularly in Vermeer’s paintings, though the item in Girl with a Pearl Earring is unusually large, leading some to believe that it was artificial. Remarkably, Vermeer conveyed its three-dimensionality with just two comma-shaped strokes, one in gray at the bottom to reflect the collar poking above her golden dress, and an impastoed daub of white on top to describe an answering reflection, perhaps from an invisible window. Vermeer elided any semblance of a hook, making it seem as if the earring were floating against the figure’s neck.

As in much of his oeuvre, Vermeer softened Girl with a Pearl Earring’s details with a barely perceptible blur, giving it the appearance of an out-of-focus photograph. This leads us to another puzzle surrounding Vermeer: whether he used a camera obscura, a device fitted with a lens that threw a projection of whatever was in front of it onto a wall or smaller surface (like a canvas). The evidence offered is that Delft had a considerable lens-grinding industry and was furthermore home to Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, inventor of the microscope and a possible acquaintance of Vermeer. Why this question persists is likely due to the idea that using the camera obscura would transform Vermeer into a sort of proto-modernist.

Whether or not a camera obscura played a role as the secret sauce in Vermeer’s work scarcely matters, however. The real power of Girl with a Pearl Earring lies in its subject’s expression, seductive yet seemingly yearning for human connection over an abyss of time.