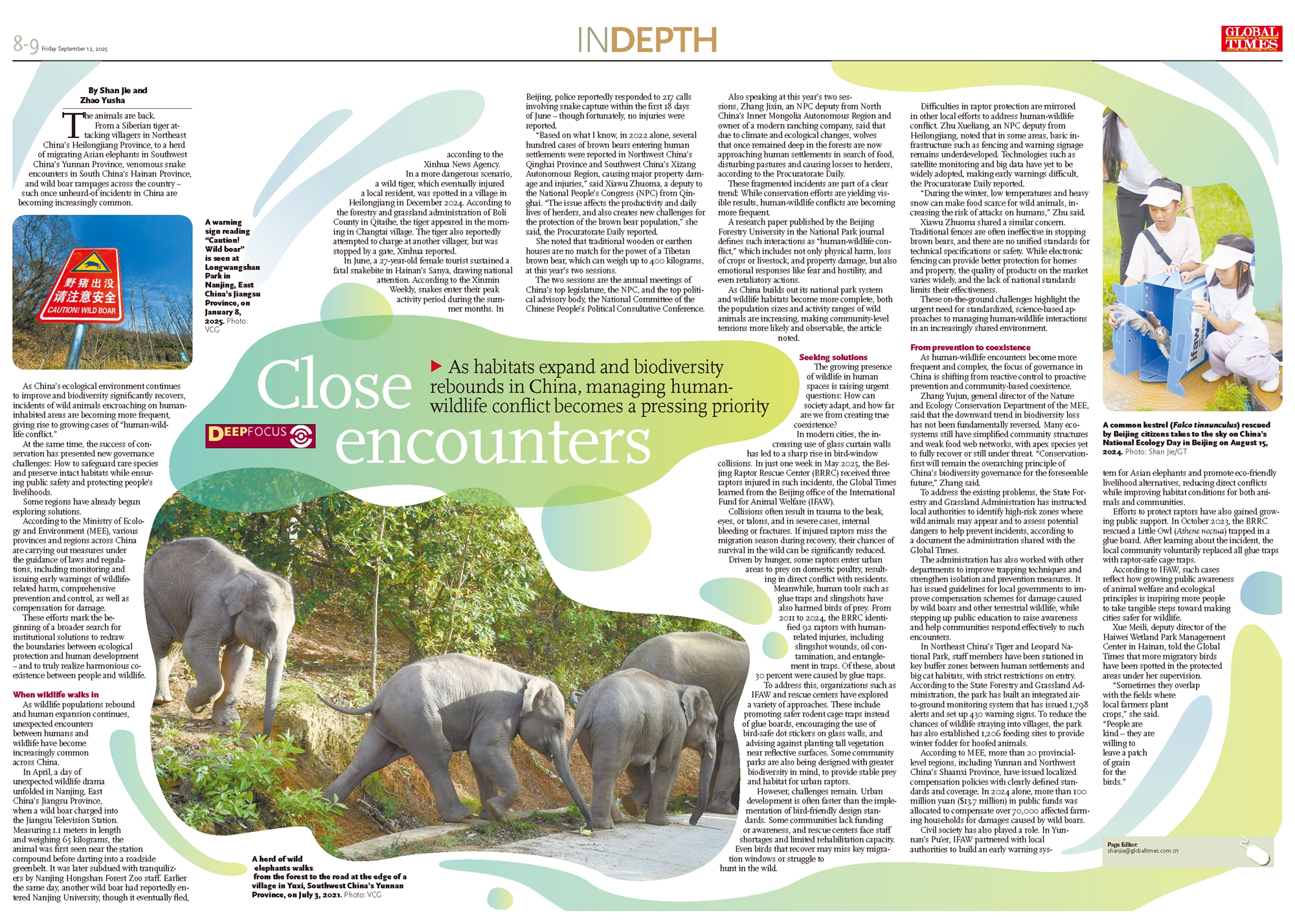

A herd of wild elephants walks from the forest to the road at the edge of a village in Yuxi, Southwest China’s Yunnan Province, on July 3, 2021. Photo: VCG

The animals are back.

From a Siberian tiger attacking villagers in Northeast China’s Heilongjiang Province, to a herd of migrating Asian elephants in Southwest China’s Yunnan Province, venomous snake encounters in South China’s Hainan Province, and wild boar rampages across the country – such once unheard-of incidents in China are becoming increasingly common.

As China’s ecological environment continues to improve and biodiversity significantly recovers, incidents of wild animals encroaching on human-inhabited areas are becoming more frequent, giving rise to growing cases of “human-wildlife conflict.”

At the same time, the success of conservation has presented new governance challenges: How to safeguard rare species and preserve intact habitats while ensuring public safety and protecting people’s livelihoods.

Some regions have already begun exploring solutions.

According to the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), various provinces and regions across China are carrying out measures under the guidance of laws and regulations, including monitoring and issuing early warnings of wildlife-related harm, comprehensive prevention and control, as well as compensation for damage.

These efforts mark the beginning of a broader search for institutional solutions to redraw the boundaries between ecological protection and human development – and to truly realize harmonious coexistence between people and wildlife.

When wildlife walks in

As wildlife populations rebound and human expansion continues, unexpected encounters between humans and wildlife have become increasingly common across China.

In April, a day of unexpected wildlife drama unfolded in Nanjing, East China’s Jiangsu Province, when a wild boar charged into the Jiangsu Television Station. Measuring 1.1 meters in length and weighing 65 kilograms, the animal was first seen near the station compound before darting into a roadside greenbelt. It was later subdued with tranquilizers by Nanjing Hongshan Forest Zoo staff. Earlier the same day, another wild boar had reportedly entered Nanjing University, though it eventually fled, according to the Xinhua News Agency.

In a more dangerous scenario, a wild tiger, which eventually injured a local resident, was spotted in a village in Heilongjiang in December 2024. According to the forestry and grassland administration of Boli County in Qitaihe, the tiger appeared in the morning in Changtai village. The tiger also reportedly attempted to charge at another villager, but was stopped by a gate, Xinhua reported.

In June, a 27-year-old female tourist sustained a fatal snakebite in Hainan’s Sanya, drawing national attention. According to the Xinmin Weekly, snakes enter their peak activity period during the summer months. In Beijing, police reportedly responded to 217 calls involving snake capture within the first 18 days of June – though fortunately, no injuries were reported.

“Based on what I know, in 2022 alone, several hundred cases of brown bears entering human settlements were reported in Northwest China’s Qinghai Province and Southwest China’s Xizang Autonomous Region, causing major property damage and injuries,” said Xiawu Zhuoma, a deputy to the National People’s Congress (NPC) from Qinghai. “The issue affects the productivity and daily lives of herders, and also creates new challenges for the protection of the brown bear population,” she said, the Procuratorate Daily reported.

She noted that traditional wooden or earthen houses are no match for the power of a Tibetan brown bear, which can weigh up to 400 kilograms, at this year’s two sessions.

The two sessions are the annual meetings of China’s top legislature, the NPC, and the top political advisory body, the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.

Also speaking at this year’s two sessions, Zhang Jixin, an NPC deputy from North China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and owner of a modern ranching company, said that due to climate and ecological changes, wolves that once remained deep in the forests are now approaching human settlements in search of food, disturbing pastures and causing losses to herders, according to the Procuratorate Daily.

These fragmented incidents are part of a clear trend: While conservation efforts are yielding visible results, human-wildlife conflicts are becoming more frequent.

A research paper published by the Beijing Forestry University in the National Park journal defines such interactions as “human-wildlife conflict,” which includes not only physical harm, loss of crops or livestock, and property damage, but also emotional responses like fear and hostility, and even retaliatory actions.

As China builds out its national park system and wildlife habitats become more complete, both the population sizes and activity ranges of wild animals are increasing, making community-level tensions more likely and observable, the article noted.

Seeking solutions

The growing presence of wildlife in human spaces is raising urgent questions: How can society adapt, and how far are we from creating true coexistence?

In modern cities, the increasing use of glass curtain walls has led to a sharp rise in bird-window collisions. In just one week in May 2025, the Beijing Raptor Rescue Center (BRRC) received three raptors injured in such incidents, the Global Times learned from the Beijing office of the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW).

Collisions often result in trauma to the beak, eyes, or talons, and in severe cases, internal bleeding or fractures. If injured raptors miss the migration season during recovery, their chances of survival in the wild can be significantly reduced.

Driven by hunger, some raptors enter urban areas to prey on domestic poultry, resulting in direct conflict with residents. Meanwhile, human tools such as glue traps and slingshots have also harmed birds of prey. From 2011 to 2024, the BRRC identified 92 raptors with human-related injuries, including slingshot wounds, oil contamination, and entanglement in traps. Of these, about 30 percent were caused by glue traps.

To address this, organizations such as IFAW and rescue centers have explored a variety of approaches. These include promoting safer rodent cage traps instead of glue boards, encouraging the use of bird-safe dot stickers on glass walls, and advising against planting tall vegetation near reflective surfaces. Some community parks are also being designed with greater biodiversity in mind, to provide stable prey and habitat for urban raptors.

However, challenges remain. Urban development is often faster than the implementation of bird-friendly design standards. Some communities lack funding or awareness, and rescue centers face staff shortages and limited rehabilitation capacity. Even birds that recover may miss key migration windows or struggle to hunt in the wild.

Difficulties in raptor protection are mirrored in other local efforts to address human-wildlife conflict. Zhu Xueliang, an NPC deputy from Heilongjiang, noted that in some areas, basic infrastructure such as fencing and warning signage remains underdeveloped. Technologies such as satellite monitoring and big data have yet to be widely adopted, making early warnings difficult, the Procuratorate Daily reported.

A warning sign reading “Caution! Wild boar” is seen at Longwangshan Park in Nanjing, East China’s Jiangsu Province, on January 8, 2025. Photo: VCG

“During the winter, low temperatures and heavy snow can make food scarce for wild animals, increasing the risk of attacks on humans,” Zhu said.

Xiawu Zhuoma shared a similar concern. Traditional fences are often ineffective in stopping brown bears, and there are no unified standards for technical specifications or safety. While electronic fencing can provide better protection for homes and property, the quality of products on the market varies widely, and the lack of national standards limits their effectiveness.

These on-the-ground challenges highlight the urgent need for standardized, science-based approaches to managing human-wildlife interactions in an increasingly shared environment.

From prevention to coexistence

As human-wildlife encounters become more frequent and complex, the focus of governance in China is shifting from reactive control to proactive prevention and community-based coexistence.

Zhang Yujun, general director of the Nature and Ecology Conservation Department of the MEE, said that the downward trend in biodiversity loss has not been fundamentally reversed. Many ecosystems still have simplified community structures and weak food web networks, with apex species yet to fully recover or still under threat. “Conservation-first will remain the overarching principle of China’s biodiversity governance for the foreseeable future,” Zhang said.

To address the existing problems, the State Forestry and Grassland Administration has instructed local authorities to identify high-risk zones where wild animals may appear and to assess potential dangers to help prevent incidents, according to a document the administration shared with the Global Times.

The administration has also worked with other departments to improve trapping techniques and strengthen isolation and prevention measures. It has issued guidelines for local governments to improve compensation schemes for damage caused by wild boars and other terrestrial wildlife, while stepping up public education to raise awareness and help communities respond effectively to such encounters.

In Northeast China’s Tiger and Leopard National Park, staff members have been stationed in key buffer zones between human settlements and big cat habitats, with strict restrictions on entry. According to the State Forestry and Grassland Administration, the park has built an integrated air-to-ground monitoring system that has issued 1,798 alerts and set up 430 warning signs. To reduce the chances of wildlife straying into villages, the park has also established 1,206 feeding sites to provide winter fodder for hoofed animals.

According to MEE, more than 20 provincial-level regions, including Yunnan and Northwest China’s Shaanxi Province, have issued localized compensation policies with clearly defined standards and coverage. In 2024 alone, more than 100 million yuan ($13.7 million) in public funds was allocated to compensate over 70,000 affected farming households for damages caused by wild boars.

Civil society has also played a role. In Yunnan’s Pu’er, IFAW partnered with local authorities to build an early warning system for Asian elephants and promote eco-friendly livelihood alternatives, reducing direct conflicts while improving habitat conditions for both animals and communities.

Efforts to protect raptors have also gained growing public support. In October 2023, the BRRC rescued a Little Owl (Athene noctua) trapped in a glue board. After learning about the incident, the local community voluntarily replaced all glue traps with raptor-safe cage traps.

According to IFAW, such cases reflect how growing public awareness of animal welfare and ecological principles is inspiring more people to take tangible steps toward making cities safer for wildlife.

Xue Meili, deputy director of the Haiwei Wetland Park Management Center in Hainan, told the Global Times that more migratory birds have been spotted in the protected areas under her supervision.

“Sometimes they overlap with the fields where local farmers plant crops,” she said. “People are kind – they are willing to leave a patch of grain for the birds.”