New research from Cambridge and the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin has decoded the mystery of magnetic fossils left by an ancient organism.

These microscopic, spearhead- or needle-shaped magnetic fragments were found in ancient seafloor sediments dating back up to 97 million years.

It turns out, these ancient remnants were the biological “GPS system” left behind, likely by an ancient eel-like creature. This internal compass allowed the unidentified creature to navigate using Earth’s magnetic field precisely.

“Whatever creature made these magnetofossils, we now know it was most likely capable of accurate navigation,” said Rich Harrison from Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences, who co-led the research.

“It looks like this creature was carefully controlling the shape and structure of these fossils, and we wanted to know why,” Harrison stated.

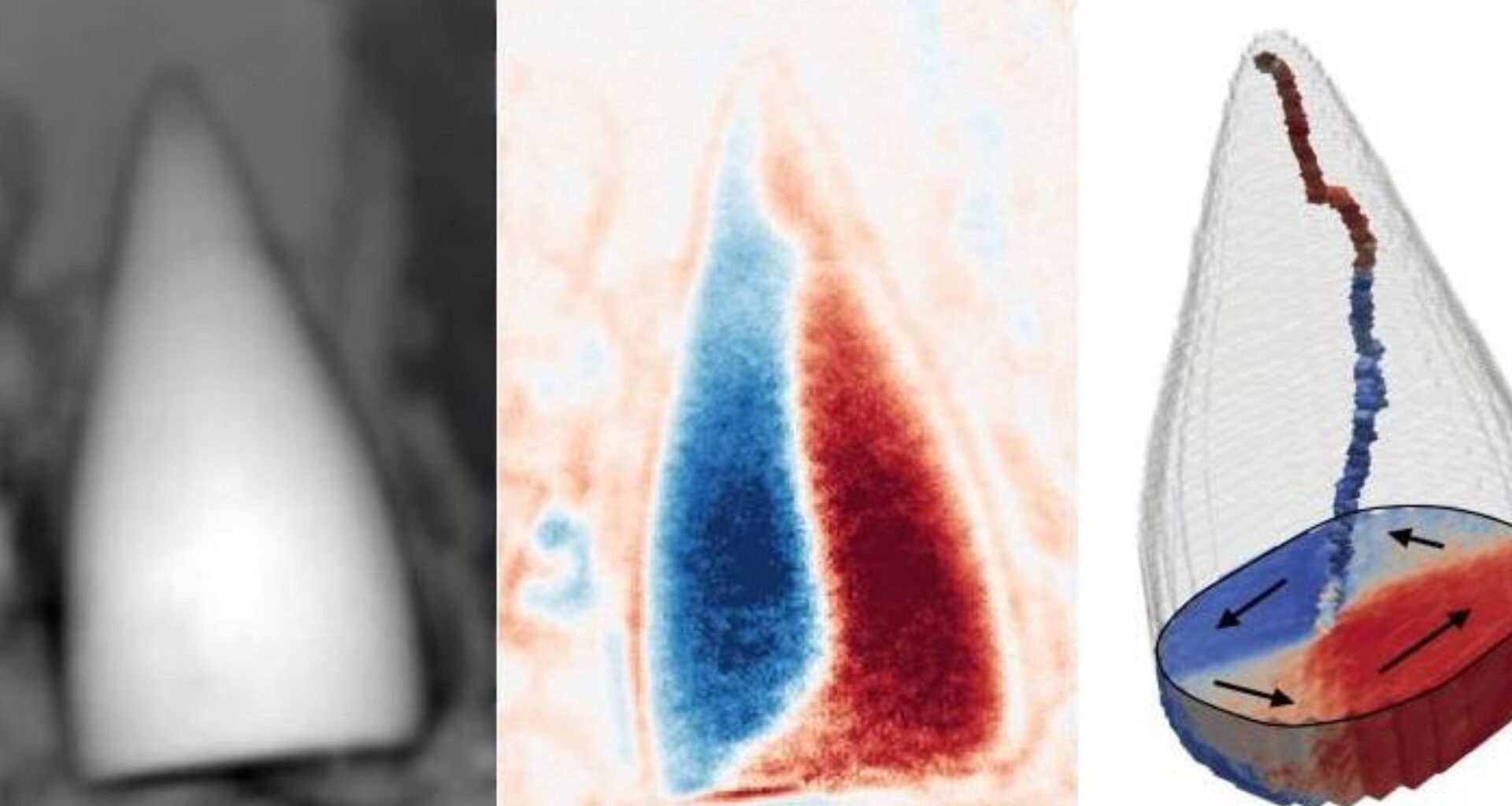

3D imaging of the tiny fossils

Magnetoreception — the ability to sense and utilize the Earth’s magnetic field — is a well-documented but still partly enigmatic sense found in the animal kingdom today.

Many species, like migratory birds, sea turtles, rely on this invisible global grid for long-distance navigation, orientation, and even hunting.

It has been proposed that tiny, internal magnetite crystals act as microscopic compass needles, aligning themselves with the Earth’s magnetic field.

However, little is known about how ancient organisms used this internal compass, or whether it was even present millions of years ago.

These new magnetofossils, which are “no larger than a bacterial cell”, offer the first direct evidence of ancient animals using the geomagnetic field for navigation.

It showcases that animals have been using the magnetic field as a map for nearly 100 million years.

For this study, the team used a new 3D magnetic imaging technique to peer inside these minuscule fossils for the first time.

Interestingly, the 3D images of the fossil’s magnetic structure revealed features optimized to guide long-distance migration by detecting the direction and strength of the planet’s magnetic field.

Search for fossils’ real creator

The technique enabled visualization of the fossil’s internal structure. It showcased the arrangement of its “magnetic moments” — tiny magnetic fields generated by spinning electrons — swirled in a vortex pattern, much like a miniature tornado.

This unique configuration, dubbed “vortex magnetism,” is the key to its navigational prowess.

“This magnetic particle not only detects latitude by sensing the tilt of Earth’s magnetic field but also measures its strength, which can change with longitude,” said Harrison.

He likened the process to a subtle “wobble” in the magnetic field, providing the organism with detailed map information. The stability of this vortex structure also meant it could resist environmental disturbances, making it a highly reliable guidance system.

“If nature developed a GPS, a particle that can be relied upon to navigate thousands of kilometres across the ocean, then it would be something like this,” the author added.

Solving the mystery of the fossils’ function allows the research to focus the search for their creator.

Earlier, it was assumed that an ancient bacteria-like creature likely left behind these magnetic remnants. However, it was not proven.

Researchers are now seeking a migratory marine animal, abundant in ancient oceans, that may have possessed such sophisticated internal navigation. One compelling candidate? Eels.

These enigmatic creatures evolved around the same time and are known for epic transoceanic migrations. Experts have long suspected that eels use the Earth‘s magnetic field, though the precise mechanism has remained elusive.

The findings could advance our understanding of how life evolved its most elusive sense of magnetoreception.

The study was published in the journal Nature.