Tweet

Email

Link

Southwest of Yokohama, Japan, Fujifilm has spent the past couple of years expanding its production facilities, pouring billions of yen into its factory as it struggles to meet global demand for its hot product: instant camera film.

In 2025, when consumers can buy a phone with a 200 megapixel camera, instant photography is thriving. An object of nostalgia or novelty, depending on your age, it’s easy to use and convenient; analog photography for hobbyists who don’t want to jump into the deep end of 35mm film.

Fujifilm’s instax is the biggest name in the game. Nearly 30 years after launching the range, in April, instax announced it exceeded 100 million units sold worldwide, with the company reporting record sales four years running.

The camera range has successfully chafed against modernity, and found new fans who are paying a dollar or more per snap.

Their appeal is “completely contrary” to the efficiency and clarity of modern digital photography, said Ryuichiro Takai, general manager of the consumer image group at Fujifilm, in a video call. And yet, “for people who take digital cameras for granted, this backward thing (instant photography) can be a completely new form of entertainment.”

It wasn’t always this popular. So why now? And what does its success say about us — as consumers, and how we view, and want to experience, life?

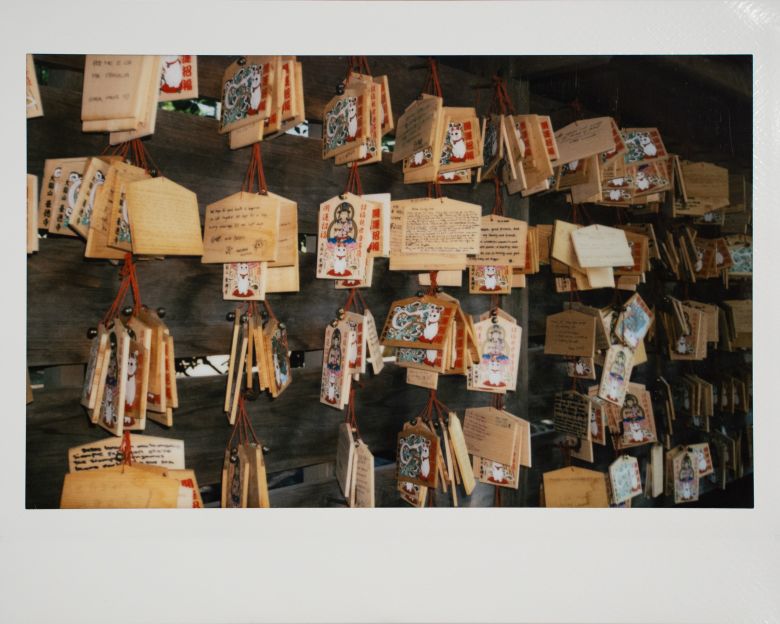

Editor’s note: For this feature, CNN producer Yumi Asada took an instax WIDE 400 around Tokyo for a week, capturing sights across the city.

The instax wasn’t the first instant camera manufactured by Fujifilm.

Polaroid and Kodak both launched instant cameras years earlier but had not made significant inroads in the Japanese market when Fujifilm introduced the Fotorama range in 1981. However, despite positive sales domestically, the Fotorama lacked a global or cultural footprint.

In the ‘90s, Takai said Fujifilm noted the popularity of purikuras — photo booths that printed photo stickers — in Japan, and sought to combine the speed and fun of them with the compactness of Fujifilm’s disposable QuickSnap camera range.

The instax mini 10, launched in 1998, was the result. A rectangle with rounded edges, the playful camera produced rectangular prints on film about 2 by 3 inches. It took off domestically, and was quickly followed by the instax WIDE range, which produced photos more than double in size, and other versions of the mini.

In 2002, the company recorded 1 million annual sales for the first time. Two years later, sales cratered to a tenth of that as digital photography became popular. Then came the smartphone. It would take the best part of a decade for instax to bounce back, with the mini 8 in 2012, marketed as “the world’s cutest camera,” said Takai, and popular among young buyers in Asia.

Polaroid, rocked by two bankruptcies, left the instant camera and film business in 2008. Instax, seizing the moment, entered the US and other international markets in 2015.

“Instax got a lot right, but it especially nailed timing,” said Jaron Schneider, editor in chief of photography publication PetaPixel. “Suddenly, Fujifilm was the only game in town that was making accessible, instant cameras.”

In 2017, instax introduced a square photo format — once synonymous with Polaroid. A year later, instax reported annual sales of 10 million cameras for the first time.

“It seems like explosive, out-of-nowhere popularity,” said Schneider. “But really, it had been heading there for several years. By 2023, Instax was over half of Fujifilm’s entire camera business. That’s outrageous growth in just a decade, but the first half of that 10-year period was spent building up and sticking with it.”

Behind the success has been some savvy product and marketing strategy. Targeting different youth culture markets, instax has collaborated with Taylor Swift and BTS, Universal Studios and Pixar on special editions, and entered partnerships with an international breakdancing series and a fashion week. It’s even reached into digital spaces: in Final Fantasy XIV, the latest edition in the Japanese video game series, players can use an instax camera as part of gameplay.

What was once a fast photography medium is now a slow novelty for younger generations. But Schneider believes the pull of analog experiences is more than just entertainment.

“Gen Z and Gen Alpha are starved for the kind of nostalgia that millennials have,” he argued. “They desperately want to have something happy to look back on before the world got so digitized, but they can’t. That’s why they flock to film photography and more tangible hobbies. Anything to get them away from their reality, which is screens, screens and more screens.

“Being constantly online is exhausting and, quite frankly, not as much fun as being in a moment with friends. Instant, and analog in general, lets you enjoy those moments and remember them without being pulled out of them.”

Takai says in the company’s research, slowing down, putting greater thought behind capturing a photograph, and the satisfaction — and security — of holding physical media were qualities liked by users across generations. “They say it’s valuable that they can ‘touch their memories,’” he said.

Tokyo-based videographer Daishi Kusunoki, 35, began using an instax this summer to document his business and personal travel. “It feels like it’s cut from the past,” he said in an email.

“(Instax) film is expensive, so I become more careful, “Kusunoki added. “Before pressing the shutter, I naturally become more aware of the light, shadow and framing.

“As I’m used to high-performance digital cameras of recent years, these restrictions can be a good way to learn about photography, and there is a sense of challenge and enjoyment to be gained from the inconvenience.”

Japan is ahead of the West when it comes to the resurgence of analog photography, said Schneider, putting it down to a culture of more “grounded” recreational activities. But he also believes there are universal factors making it increasingly attractive.

“We’re seeing a return to analog because people see it as a more genuine and authentic imaging format. There’s no AI, no editing, just a moment captured in time,” he argued. “This was something we saw quite a bit of before the big AI boom, but it’s definitely more the case now in the face of constant slop being shoved in front of us.”

Instant photography, for all its limitations, is an accessible bulwark against modernity, where seeing is not always believing.

“It’s reactionary and retrograde,” Takai said. “When people ask, ‘Why is instax received so positively in this digital age?’ we simply say, it’s going against time.”

That’s not to say instax hasn’t put one foot in the present; for over a decade it’s produced standalone printers that connect to smartphones, and launched hybrid cameras with digital sensors, capable of printing photos but also sharing them on social media. But the common denominator is the small handheld prints, which have remained largely unchanged since the turn of the century.

Today, instax cameras are available in over 100 countries, and 90% of sales are outside Japan, per Fujifilm, pointing to instant photography’s global appeal. Even Polaroid is back, revived as a brand in 2020 and trying to make up for lost time. “They’re trying to rekindle the lightning in the bottle that Fujifilm had, but everyone knows it’s not that easy,” noted Schneider.

For Fujifilm, consistency and playing the long game have paid off.

“Our team (positioned) instax to become a culture that will take root throughout the world, and not a transient boom,” said Takai. “That’s the direction.”