Work performed at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory has unlocked new data on the design of fusion fuel targets, a fundamental part of the future of inertial fusion energy (IFE).

The research, published in Physics of Plasmas, focused on how a promising class of fuel capsules—3D-printed foams—perform under extreme conditions.

In an IFE reaction, a fuel capsule the size of a pea is subjected to powerful lasers that drive an implosion, fusing atoms to release energy.

However, before this technology can be integrated into the power grid, scientists must perfect the fuel targets. These complex cylinders must hold deuterium and tritium fuel and withstand heat hotter than the Sun and pressure greater than a planet’s interior. Additionally, they must compress symmetrically without defects and be easy to mass-produce.

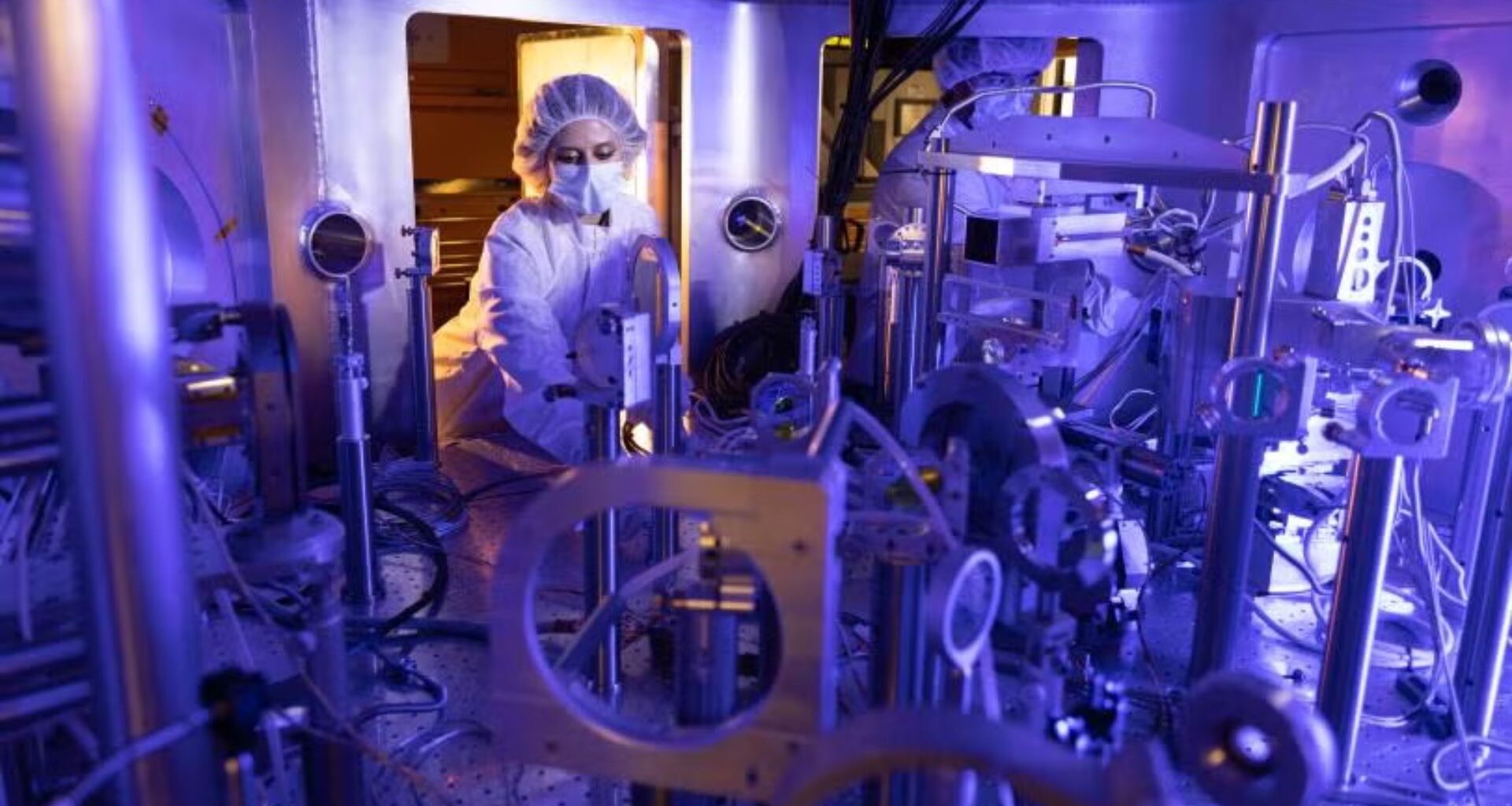

“At SLAC, we’re inventing new ways to study these fusion fuel targets and their potential behavior under the extreme conditions of a fusion power plant,” said Arianna Gleason, a staff scientist at SLAC.

Four key studies explore different challenges

The four studies utilized SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) to explore different challenges in target design.

One study, led by PhD candidate Willow Martin, focused on temperature measurement. The team used a combination of spectroscopy and scattering techniques to capture time-stamped temperature measurements, observing how carbon samples evolved from solid to plasma. This helped distinguish how much energy heats the material versus compressing it.

Another study, led by graduate student Claudia Parisuaña Barranca, imaged how shockwaves travel through 3D-printed TPP (two-photon polymerization) foams. By comparing these to conventional aerogels, the team gathered data to validate simulation models used to predict target performance.

In a separate study, undergraduate student Levi Hancock utilized ptycho-tomography to image a single pillar of TPP foam just 10 microns wide. Despite the challenge of working with low-density materials, the team successfully built detailed 2D and 3D images to aid in material design.

Finally, graduate student Daniel Hodge focused on tiny imperfections, or “voids,” in capsule shells that can reduce energy output. His team created deliberate voids and subjected them to laser-driven shockwaves to understand how these imperfections influence compression.

Setting stage for future research

The research is part of the DOE Inertial Fusion Energy Science and Technology Accelerator Research (IFE-STAR) program. According to Gleason, these studies outline the experimental frameworks necessary for future density, pressure, and imaging studies.

“It’s a grand scientific challenge to make fusion energy a real, sustainable power source,” concluded Martin.

“Contributing to a technology that could be so revolutionary for human society is a strong motivator.”

In another development, the University of California San Diego has identified how diamond capsules used in nuclear fusion experiments can develop structural flaws under the high pressures required for the process.

The findings can help guide improved capsule designs and models to achieve more uniform implosions, and thus maximize the energy output of fusion experiments.

The results from this study on deformation mechanisms may contribute to a more comprehensive constitutive understanding not only of diamond but also of covalently bonded materials in general.