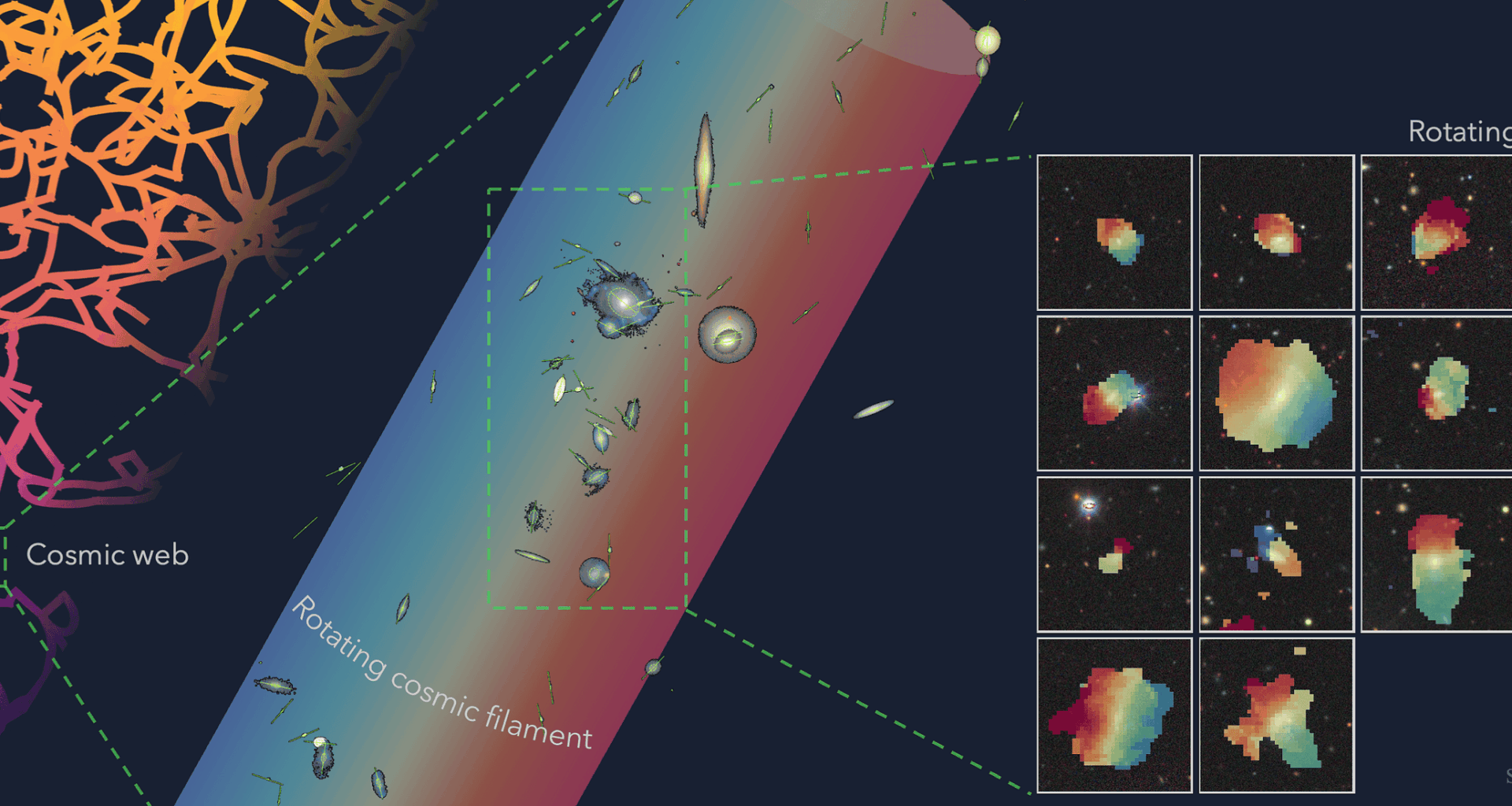

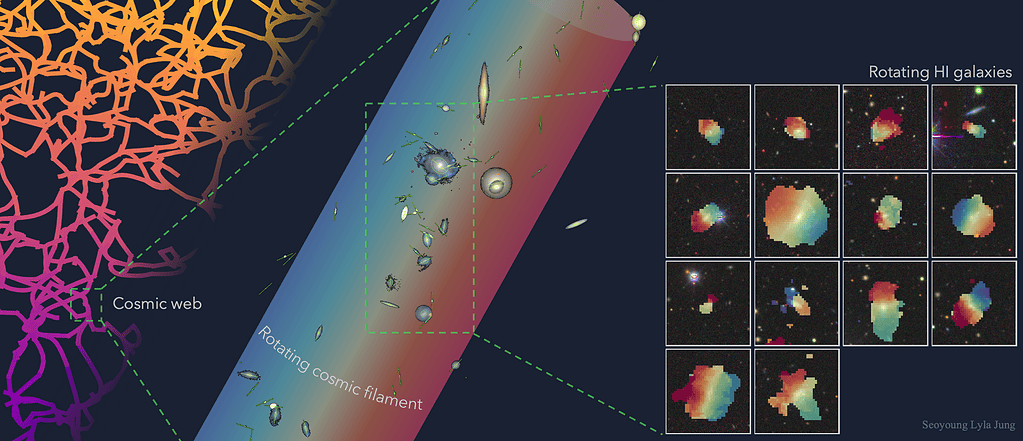

This spinning branch of the cosmic web binds 14 galaxies together. Credit: Lyla Jung.

This spinning branch of the cosmic web binds 14 galaxies together. Credit: Lyla Jung.

In a recently published study, astronomers using South Africa’s MeerKAT radio telescope have identified what could be the largest rotating object ever observed in space. The object itself is a vast strand of the cosmic web, with a thin line of 14 gas-rich galaxies running along it like beads on a string. The structure lies about 140 million light-years away and spans tens of millions of light-years.

What are cosmic filaments?

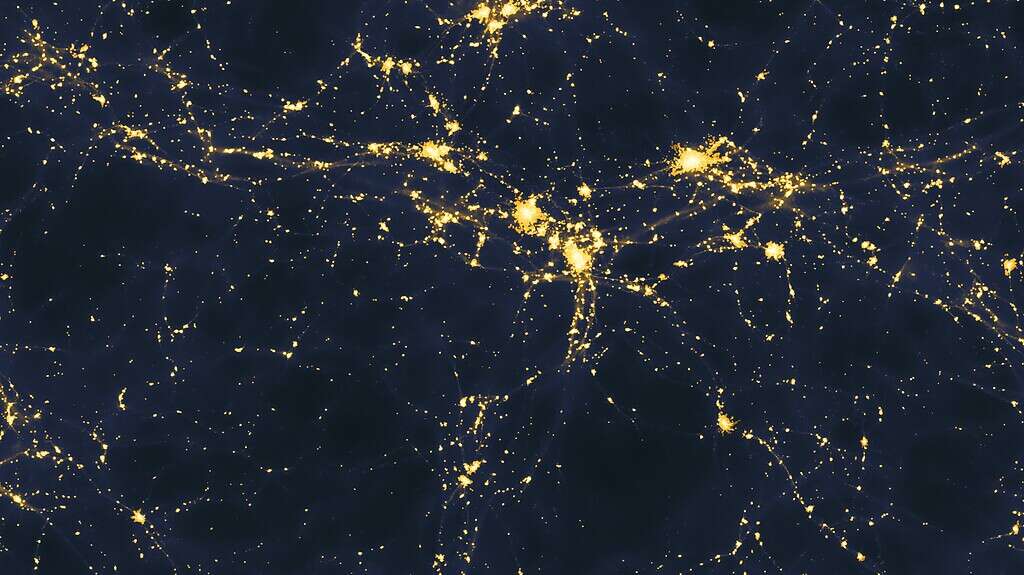

Computer simulation of galaxy filaments, walls and voids forming web-like structures across the universe in a 2014 UCLA study. Credit: Andrew Pontzen/Fabio Governato, UCLA

Computer simulation of galaxy filaments, walls and voids forming web-like structures across the universe in a 2014 UCLA study. Credit: Andrew Pontzen/Fabio Governato, UCLA

On the largest scales, the universe looks like a network. Crowded regions connect through long, thread-like bridges. Those bridges are cosmic filaments: Enormous lanes where matter is more concentrated than the emptier regions around them. Over time, gravity nudges gas and galaxies along these lanes toward busy intersections, shaping how galaxies grow.

The team’s first clue as to the object’s existence was an unusual alignment in deep radio data: 14 nearby galaxies rich in atomic hydrogen arranged in an unusually straight, narrow chain. The researchers describe the inner string as about 5.5 million light-years long and “only” about 117,000 light-years wide — though that’s still wider than the Milky Way. At that scale, “razor-thin” is not an exaggeration.

Then the researchers zoomed out using major optical galaxy surveys, including the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. That broader map showed the 14-galaxy chain sits inside a far larger cosmic filament traced by hundreds of galaxies and reaching roughly 50 million light-years from end to end. The skinny chain is not the whole filament; it’s a crisp marker sitting inside a much broader structure.

Why MeerKAT and hydrogen made the difference

MeerKAT can detect faint radio emission from atomic hydrogen, the most common element in the universe and a key ingredient for star formation. Hydrogen also helps track motion. When a galaxy rotates, hydrogen gas on one side of its disk moves toward us while the other side moves away, shifting the radio signal across the galaxy. That lets astronomers map how a disk spins, not just where it sits.

Here, hydrogen-rich galaxies worked like signposts. Once those signposts were in place, optical catalogs filled in the surroundings and traced the filament well beyond the deepest radio footprint.

The headline result is not only that galaxies spin, but also that the filament may rotate as a whole. The researchers compared galaxy motions on opposite sides of the filament’s centerline. They found a split: galaxies on one side tend to move slightly away from us, while galaxies on the other side tend to move slightly toward us. That contrast matches what rotation would produce, like a slow carousel where one edge approaches and the other recedes.

From this velocity pattern, the team estimates a rotation speed of around 110 kilometers per second (roughly 246,000 miles per hour).

The study also reports that many of the galaxies’ spin directions line up with the filament more strongly than common computer simulations predict. Put simply, the galaxies do not look randomly oriented. Their spins appear tied to the strand they live in, hinting that filament environments can shape rotation for longer — or more strongly — than models usually allow.

“What makes this structure exceptional is not just its size, but the combination of spin alignment and rotational motion,” said Lyla Jung, a co-lead author at the University of Oxford.

“You can liken it to the teacups ride at a theme park. Each galaxy is like a spinning teacup, but the whole platform- the cosmic filament -is rotating too. This dual motion gives us rare insight into how galaxies gain their spin from the larger structures they live in.”

Why this matters for galaxy formation

Astronomers already view cosmic filaments as delivery routes for gas. If a filament carries a coherent twist, it may also pass angular momentum — spin — into the galaxies growing inside it. Co-lead author Madalina Tudorache described the system as “a fossil record of cosmic flows,” meaning it preserves clues about how motion in the cosmic web can influence galaxies.

The researchers also describe the filament as relatively young and not heavily disturbed, with many gas-rich galaxies and signs of orderly motion. In denser regions, galaxy interactions can scramble spin directions and blur any tidy alignment signal.

Currently, this is one unusually clear example revealed by the overlap of deep hydrogen mapping and wide optical surveys. The team expects more rotating filaments to appear as MeerKAT observations deepen and galaxy catalogs expand. If many more show bulk rotation plus aligned galaxy spins, astronomers will have a sharper test for how well simulations capture the way the cosmic web passes motion down to galaxies.

The findings appeared in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.