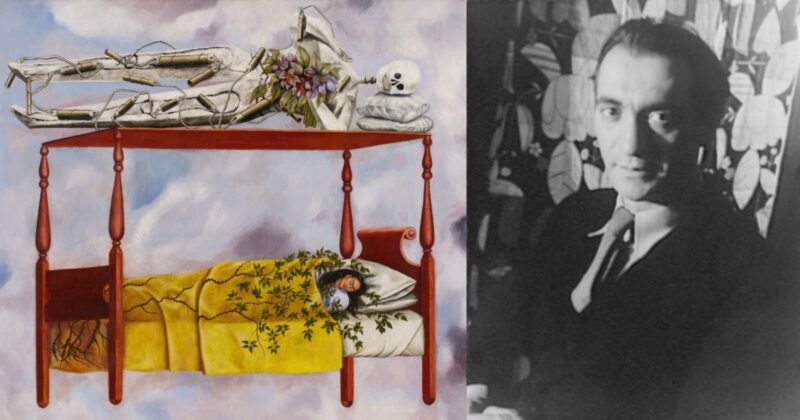

The Dream (The Bed) by Frida Kahlo (left) sold for a record-breaking $55m last month. The artwork was a gift for American-Hungarian photography pioneer Nickolas Muray (right) who took some of the most famous portraits of the Mexican artist.

The Dream (The Bed) by Frida Kahlo (left) sold for a record-breaking $55m last month. The artwork was a gift for American-Hungarian photography pioneer Nickolas Muray (right) who took some of the most famous portraits of the Mexican artist.

Last month, The Dream (The Bed) by Frida Kahlo sold for $54.7 million, breaking the auction record for a work by a woman. Fascinatingly, Kahlo’s 1940 painting was created for — and inspired by — American photographer Nickolas Muray, who produced some of the most iconic portraits of the artist.

Mexican artist Kahlo’s work The Dream (The Bed) (officially titled El sueño (La cama)) depicts her asleep in a canopy bed beneath a grinning papier-mâché skeleton wrapped in sticks of dynamite. Painted during one of the most turbulent periods of her life, the piece explores the blurred boundary between rest, pain, and mortality. It sold at Sotheby’s after four minutes of bidding for $54.7 million, achieving a price more than 1,000 times higher than its 1980 auction result.

According to a report by EL PAIS, Martín Lozano, a historian of Mexican and Latin American art, notes that Kahlo created the “complex self-portrait” for American-Hungarian photography pioneer Nickolas Muray, her lover for a decade and the photographer who captured her image more than anyone else.

Muray was among the most successful portrait and fashion photographers working in New York during the 1920s. He also helped transform commercial photography through his pioneering use of colour, particularly the three-colour carbro process, which became a hallmark of his style. His editorial and advertising work played a major role in shifting American commercial imagery toward natural-colour photography in the 1930s.

Nickolas Muray’s ‘Girl in Red’ (1936) which was an ad photo for Lucky Strike cigarettes (Wikimedia Commons/ Public Domain)

Nickolas Muray’s ‘Girl in Red’ (1936) which was an ad photo for Lucky Strike cigarettes (Wikimedia Commons/ Public Domain)

Muray first met Kahlo in 1931 during a trip to Mexico, after being introduced by artist Miguel Covarrubias and his wife, Rosa. Muray had struck up a friendship with the couple in New York when they visited his Manhattan salon, where he photographed subjects ranging from Clara Bow to Greta Garbo. Accepting their invitation to stay with them in Mexico City, Muray met Kahlo and formed an immediate connection. The two began a romantic relationship that lasted until 1941 and a friendship that continued until her death in 1954.

Across his career, Muray created an archive of more than 25,000 images, yet his portraits of Kahlo stand out as some of his most significant and famed. He photographed her more than any other subject. His images — showing her at home, in her studio, with friends, or dressed in her now-iconic Tehuana clothing — became central to the global visual understanding of Kahlo that emerged after she died. These portraits appear widely in books, exhibitions, popular culture, and museum collections, shaping the way the world perceives the artist behind the paintings.

Muray and Kahlo’s relationship unfolded during a period of considerable upheaval for her. When she returned from Paris in 1939, she learned that her husband, Diego Rivera, wanted a divorce, a development that deeply affected her. Although their marriage had long been unconventional, Kahlo was striving for independence: she had sold paintings in New York, had work acquired by the Louvre, and received steady emotional and financial support from Muray.

Lozano tells EL PAIS that Muray “was a support, a man who loved her and asked for nothing in return.”

However, Muray wanted to marry Kahlo, and when it became clear she did not want a husband — she wanted him as a lover — he withdrew from the relationship and later married his fourth and final wife, Margaret Schwab.

In the EL PAIS report, Lozano explains that Kahlo created The Dream (The Bed) as a gift to thank Muray for his years of kindness. She was close to finishing the painting when she learned of Muray’s plan to remarry.

“It’s a painting that deals with dreams, yes, but it also relates to that reality constructed in Frida Kahlo’s subconscious,” he says. “What happens in that constructed reality? She has peace: she’s detached from the conflict of Rivera’s divorce, detached from the conflict of her illness and her pain, and she’s at peace when she’s with Nick, because she’s very happy with Nick Muray.”

Lozano adds that the happiness reflected in the painting “crumbled with the announcement of the upcoming nuptials,” and Kahlo could no longer bring herself to give the work to Muray. She later told him she had already sold The Dream (The Bed) due to financial necessity — a claim contradicted by its 1940 date and by letters from 1939. She continued offering the painting to American collectors for $400, even though Muray believed it was already out of her hands.

The painting was eventually shown at the Misrachi Gallery in Mexico City, where it was purchased by collector Luis de Hoyos. Despite the rupture surrounding the artwork, Muray and Kahlo remained close until she died in 1954. Muray’s final photo session with Kahlo took places in 1946, when she travelled to New York for her last spinal surgery. In the now-iconic photos, Kahlo is seen smoking a cigarette on Muray’s apartment rooftop.

Image credits: Header photo via Sotheby’s Auction House (left) and Library of Congress (right).