President Vladimir Putin has often proclaimed that Russia must lead the world in artificial intelligence. In reality, the country is stuck on the sidelines as others pull ahead.

PREMIUM Russian President Vladimir Putin, in red tie, at an AI forum in Moscow with Sberbank CEO Herman Gref. The state-owned lender leads Russia’s AI efforts.

PREMIUM Russian President Vladimir Putin, in red tie, at an AI forum in Moscow with Sberbank CEO Herman Gref. The state-owned lender leads Russia’s AI efforts.

As the U.S. and China race to dominate AI models and applications and countries in Europe and the Middle East pour resources into building computing infrastructure, the Ukraine war has derailed Russia’s once lofty ambitions.

On the Russian-language version of LM Arena where users rate AI models, the top-performing Russian model ranks 25th, trailing behind even older iterations of ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini. According to Stanford University’s Global AI Vibrancy Tool, which was released in November and measures the strength of countries’ AI ecosystems, Russia ranks 28th out of 36 countries.

Western sanctions choked off Russia’s access to critical hardware such as computer chips and hamstrung its domestic production abilities. Russian companies now depend on middlemen in third countries to secure everything from high-end chips to even a simple ChatGPT subscription. Moscow has also leaned heavily on China—further deepening what analysts already describe as an economic vassalage to its neighbor.

Compounding the problem is a brain drain, with top talent fleeing Russia after the invasion of Ukraine. Cut off from international markets, Russian AI companies attracted about $30 million in venture funding last year. OpenAI alone raised more than $6 billion last year.

“Russia is years behind in developing its own AI,” said Yury Podorozhnyy, a former Russian tech executive.

Podorozhnyy has witnessed the arc of AI development in Russia firsthand, having spent years developing the local equivalents of Google Maps and Netflix, including working on machine-learning tools now central to the AI boom. Shortly after the outbreak of the war in 2022, he boarded a plane and escaped Russia with his pregnant wife.

“Russia has already lost in the competition and it’s impossible to catch up,” said Podorozhnyy, who now lives in London and is chief AI officer at fintech startup Finom.

A Moscow-based AI executive agreed with that assessment and said that Russia’s economic and geopolitical isolation prevents companies from accessing funding and gaining the ability to scale beyond their comparatively small domestic market.

With AI’s potential to reshape the global economy, countries are scrambling to assert control over their AI infrastructure, data and models to avoid strategic dependence. In the military domain, too, readiness increasingly depends on sovereign AI capabilities, from battlefield decision-support tools to autonomous defense systems.

For Moscow, this imperative is especially acute given its escalating standoff with the West.

“We cannot allow critical dependence on foreign systems,” Putin said at an AI conference last month. “For Russia, this is a matter of state, technological and value sovereignty.”

A Polish soldier carries an AI-powered antidrone system in Nowa Deba, Poland. Western sanctions have choked off Russia’s access to critical hardware.

A Polish soldier carries an AI-powered antidrone system in Nowa Deba, Poland. Western sanctions have choked off Russia’s access to critical hardware.

Russian officials have acknowledged the shortcomings, but say that domestic models rival foreign ones and are improving fast. Others are more blunt.

“The vast majority of our industries are millions of light years away from AI,” Herman Gref, the chief executive of state-owned lender Sberbank, which is leading Russia’s AI efforts, said earlier this year.

It isn’t just Russia’s AI models that are falling behind.

At a Moscow tech conference in November, the country’s first AI-equipped humanoid robot—named AIDOL—hobbled onstage to the “Rocky” theme, attempted a wave and promptly toppled over. Organizers cut the demonstration short and removed the machine. The organizers said the robot will learn from the “consequences of its own actions.”

Even before the invasion, Russia was relying largely on foreign technology to design chips and had limited chip-production capabilities of its own. Some of the leading Russian-designed chips were assembled by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.

In 2022, the U.S. imposed a ban on selling high-tech products including semiconductors to Russia, with the ban extending to certain foreign items produced with U.S. equipment, software or blueprints. South Korea and Taiwan, which dominate in high-end chips, and Japan, strong in chip-making materials and tools, also promptly banned exports of such items. TSMC halted the export of semiconductors to Russia.

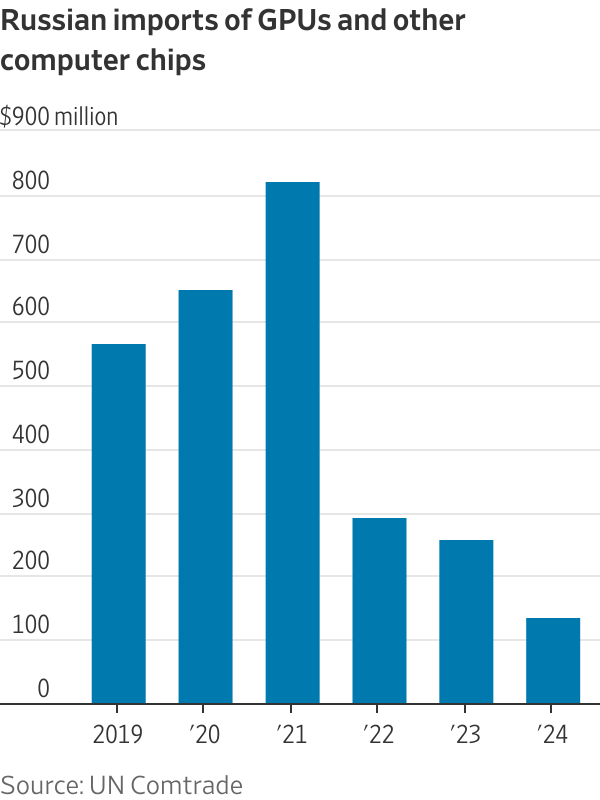

Russia was suddenly unable to directly purchase high-performance graphics processing units, or GPUs, essential for training AI models, including the latest Nvidia chips. A Wall Street Journal analysis of United Nations trade data shows that Russia’s imports last year of GPUs and other computer chips essential for AI development have fallen 84% from before the war.

Chart.

Chart.

“There’s a big lack of GPUs in Russia and what they have is not nearly enough even for current needs,” said Podorozhnyy, who still keeps in touch with AI experts in Russia. The Moscow-based AI executive concurred and said that advanced GPUs are accessible only through “hacks” such as intermediaries.

While analysts say that it is possible to buy chips via China or Central Asian neighbors, Podorozhnyy said that “the crucial problem is buying them at scale.”

The sanctions also cut off Russia’s access to materials and components needed to re-create production of such items locally. Russian chip makers are now aiming to produce 28-nanometer chips in domestic factories by 2030. American chip makers are currently transitioning to 2-nanometer chips.

Even paying for foreign models such as ChatGPT is a hassle, now that Russian cards no longer work abroad. Russian sites tout workarounds that range from using bank cards issued in Kazakhstan, Armenia or the United Arab Emirates to online gift cards or payment intermediaries. Telegram channels teem with users trading tips and middlemen peddling their services.

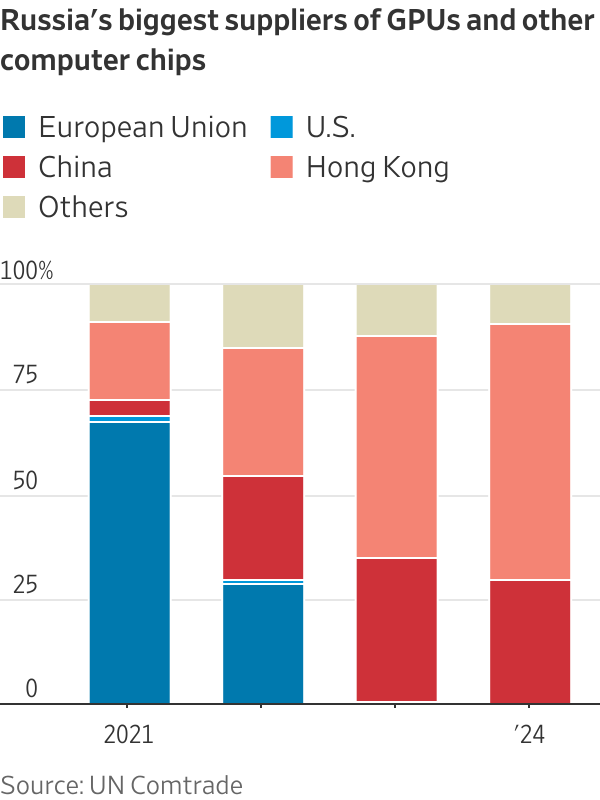

Sanctions have made Russia’s AI development deeply dependent on China, echoing patterns across the Russian economy.

At the start of the year, Putin ordered Russia’s government and Sberbank to work on AI research and development with China. It was an acknowledgment of a trend that has only grown since the Ukraine invasion.

According to the Journal’s trade-data analysis, in 2021 about 22% of Russia’s GPUs and other advanced parts came from China and Hong Kong. Last year, their share in Russia’s imports rose to 92%.

Chart.

Chart.

Some leading Russian models, meanwhile, are based on Chinese open-source models.

Even if Russian companies find workarounds to import technology or hardware, the country is bleeding another essential resource: talent.

Russian officials have said that at least 100,000 information-technology specialists left in 2022 alone and haven’t returned. The Labor Ministry has predicted that, by 2030, Russia will be lacking more than 400,000 IT workers. Some analysts say the actual number is much higher.

Anna Fedosova, who has worked in Russia’s tech sector, estimated that 70% to 80% of Russia’s most talented AI workers have left the country. Fedosova is now based in Prague having co-founded Copilotim, a startup that provides an AI-powered platform to automate human-resources administrative and compliance processes.

“It’s very difficult to hire a top tier AI engineer in Russia at the moment,” Fedosova said. “That makes it a challenge to make AI breakthroughs there. It’s definitely a big loss for the country.”

Write to Georgi Kantchev at georgi.kantchev@wsj.com