Shanti Mathias reads the latest young adult novel from Elizabeth Knox.

Kings of This World opens dramatically: a child with broken ribs is taken to hospital by her father. She is in pain. He leaves her there, with blurry, incomplete memories when authorities ask her what has happened. In the intentional community they belong to, everyone is dead.

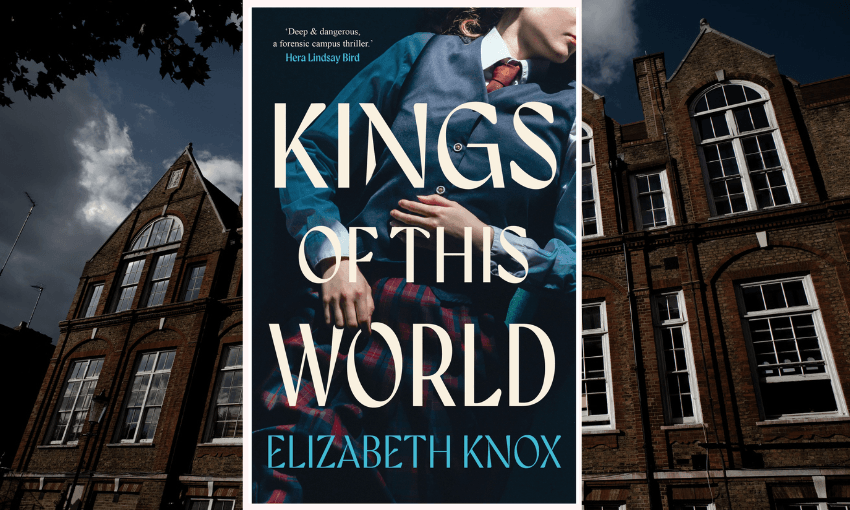

This is Elizabeth Knox’s reintroduction to Southland, the setting she first gave us in her Dreamhunter and Dreamquake duology. Those two books were mainstays of my high school library: I read them again and again. Southland is a kind of alternative New Zealand: a British-influenced island country, isolated from the rest of the world. Unlike Aotearoa (as far as we know), it has magic. Now, more than 10 years since Mortal Fire, her most recent book marketed to young adults, Knox is back.

Dreamhunter and Dreamquake are about families who can cross the border into another place to harvest dreams: beautiful dreams and terrifying dreams; dreams that can be shared and sold. Kings of This World focuses on another type of supernatural power, called “P”: P to Push or Persuade, to change another person’s mind or reorient their feelings. It’s set, approximately, in the present day. There are phones and cameras and computers, and this technology helps propel the story.

The child from the opening sequence is Victoria Magdolen, now in her final year of school and calling herself “Vex”. Everyone knows who her father is: the mass murderer who used his P to kill. She doesn’t like to talk about him, though. Raised in foster care, Vex has had the opportunity to join the exclusive Tiebold Academy, a school where the majority of students have P and are taught to use it appropriately.

In the “dark academia” setting – school uniforms, high walls, beeswax-polished corridors and persistent danger – Kings of this World reminded me of The Raven Boys by Maggie Stiefvater, a series of novels about a private school, a girl who doesn’t fit in, and the collision of wealth, poverty and magic powers. Knox is interested in similar themes. But what is most compelling about this novel is the concept of P itself.

Elizabeth Knox at home. (Photo: Robert Cross)

P is possibly the least flashy form of magic I’ve ever come across in a fantasy novel. What makes it compelling is how hard it is to tell whether it’s working. As Vex notices, an influential senator (and father of her classmate Ari) is “warm, smart, straight-forward, good-humoured and handsome.” It’s easy to agree with what he says for all those reasons – and especially easy to agree with him because he has P. In this way, the supernatural power of P is both associated with, and metaphor for, wealth and beauty and power, all those other qualities which make it easier to shape the world to your will and change the behaviour of people around you.

Knox’s books need to be read with your brain on; this was certainly my takeaway from The Absolute Book, her previous blockbuster (and door-stopper) novel. In Kings of This World, a close-third narration sticks firmly to Vex, but most of the plot unfolds through dialogue. I found myself flipping back to previous chapters to reread a conversation to make sense of what each character might want. The primary action of the novel unfolds with Vex and five others being kidnapped, while alternating chapters establish how these friendships formed.

Vex, understandably, is a spiky protagonist. She’s good at blocking P “in her fortress, drawbridge up and windows shuttered”. It’s hard for kidnappers, P-pushers, friends and readers to get into her mind, even Ari with his “surgically sharp empathy”. This characterisation still works, because Knox gives us these occasional lovely sentences. Take this, when Vex starts watching Ari perform a gymnastics routine. “Vex felt as if she’d stepped into a swarm, a clod of something alive that overwhelmed her senses. Not something dangerous like bees, but something tender, like a storm of cherry blossom.” It’s effective because these descriptive passages are mostly surrounded by sharp, punchy dialogue.

Perhaps the most obvious way in which this story feels appropriate for young adult audiences (as well as adults) is how Knox evokes the tangled complexity of a crush and friendship, layered on top of each other. Knox is equally good at Vex’s determined dislike of some characters, like Helen, a key adult. “Vex felt that she and Helen were two plates of sea ice rammed together and making sharp glassy ridges.” Beat, beat; dialogue, dialogue. The glassy ridges form as Helen and Vex talk, both with something to hide.

The combination of mystery, danger and fast-fused friendship created by the kidnapping makes for propulsive reading: I picked the novel up and found myself staying up with the lamp on until the final pages. But while Knox creates a near immaculate storyline within the kidnapping plot, the threads start fraying when the characters encounter the rest of the world.

There’s persistent risk from a group called Sons and Daughters of the Turning who may or may not be the kidnappers. But their motivations are not fleshed out. At times, advancing the plot relies on Vex and co believing their kidnappers, who have good reason to deceive. A final revelation about Vex’s father wasn’t given the breathing space for Vex to feel its emotional weight, while another twist about the nature of Vex’s P powers had been signalled so frequently it was extremely obvious.

Hannu, another of Vex’s friends, is the son of a billionaire, and I wished that Hannu’s access to this advanced technology had been used to better effect in the plot. While cameras and microphones are part of the kidnapping plot, why introduce a phone that can evade cell signal blockers, only to use it merely to avoid a school phone ban and ask about sending a letter, a more outdated technology that actually does shape an outcome? It would also have been good to know something more about Vex’s foster parents and previous schooling, even a scant paragraph, to give more context on why she falls so hard and fast into friendships at her new school.

While the last fifth of the novel was a little untidy, not quite meeting the ambition of the set-up, Kings of This World is so fun to read that I didn’t mind too much. It’s perfectly pitched at teenagers wrapped up in intense friendships and starting to notice the politics of inequality, immigration and power, and the open danger makes it just as riveting for adults. It’s a joy to see that the brainy, evocative weirdness of The Absolute Book is still present as Knox returns to writing for young adults.

Perhaps the best endorsement I can give Kings of This World is that two weeks after I finished reading, I dreamt about it, and woke feeling elastic and whirly, like I had eaten a stormcloud in my sleep.

Kings of this World by Elizabeth Knox (Allen & Unwin, $30) is available to purchase from Unity Books.