Artist and photographer Alexander Newman Hall went viral recently for a laser photo he created for a multimedia project. However, the internet success came at a great cost, as Hall broke his camera.

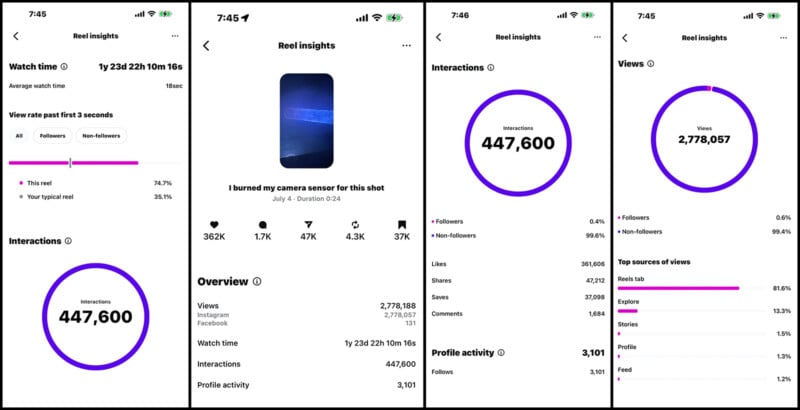

When Alexander Newman Hall reposted an old laser experiment to Instagram, he treated it as just another post in his mission to understand social media. It was one clip among hundreds he was pushing out each week, part of a much larger personal challenge to test how ideas move online. Yet almost immediately, it became the most successful piece he had ever shared. The caption alone froze people mid-scroll. It hinted at danger, commitment, and consequence, far more than the typical polished loop or visual effect audiences are used to.

“I burned my camera sensor for this shot,” the caption says. Simply put.

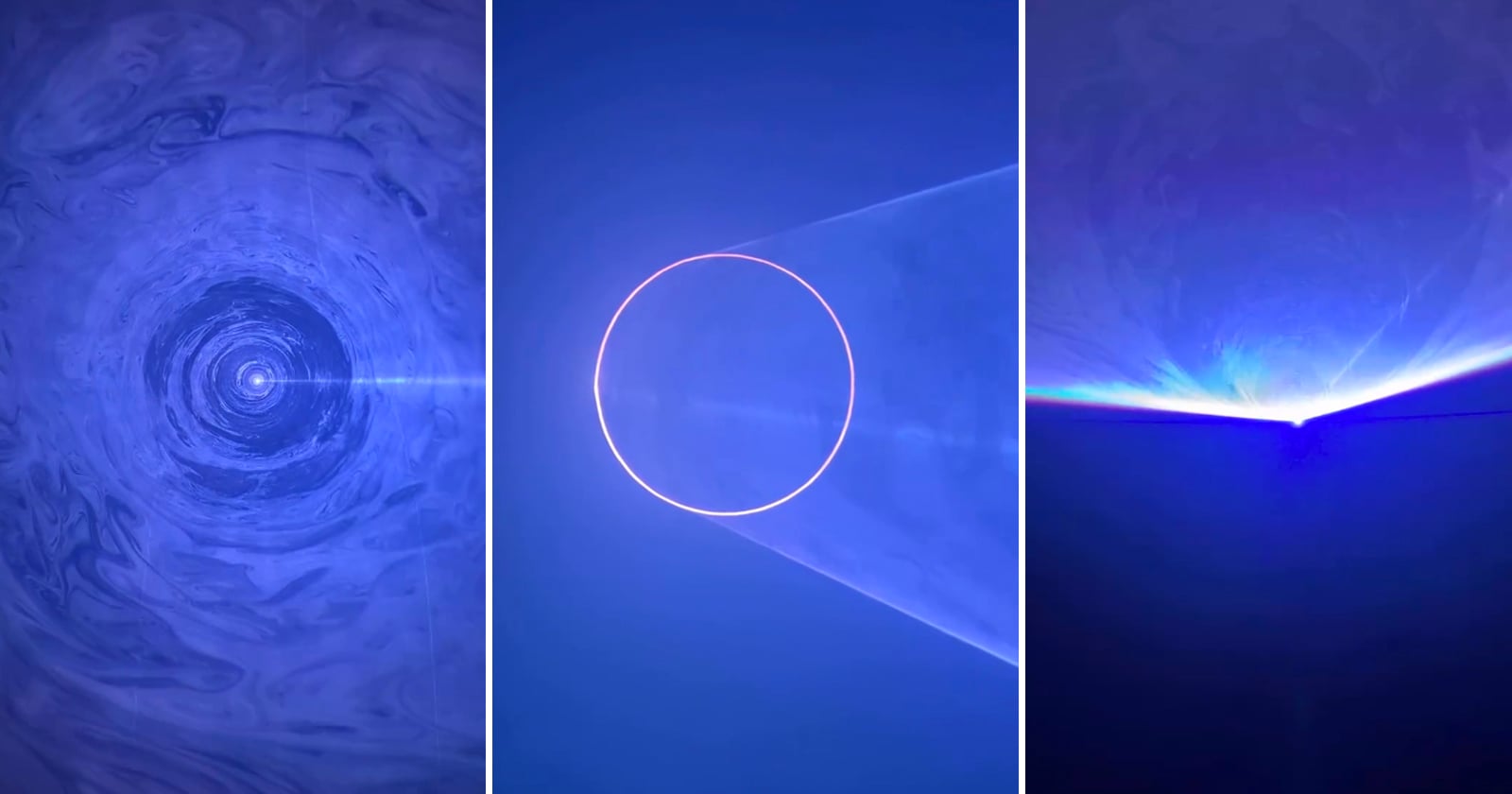

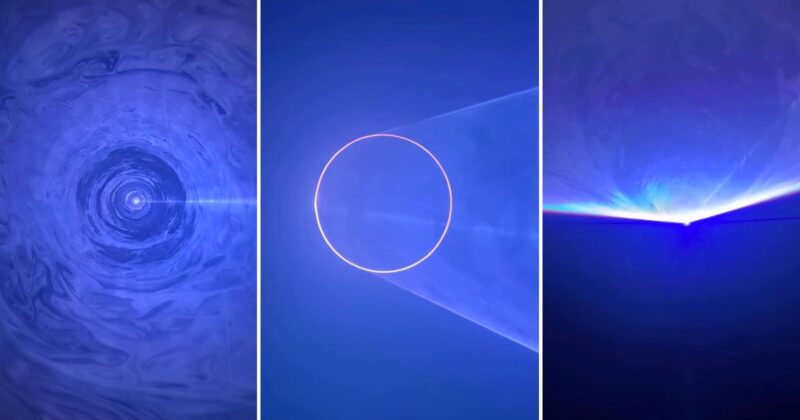

The risk in the video feels genuine. Fog wraps a room in a soft haze, transforming a technical experiment into something cinematic. A laser draws a flawless circle, rotating with eerie precision. As the beam crosses the iPhone recording the scene, the image begins to fracture violently, glitching in a way that feels both alarming and mesmerizing. The beam leaves behind a permanent purple streak on every future frame, a scar that becomes part of the phone’s visual DNA. It is chaotic and strangely beautiful. But the roots of that moment come from years of experimentation across art, tech, and instinctive play.

The Studio Where Experiments Became a Practice

Before the laser clip resurfaced, Hall was in the middle of an intensive period of exploration. In 2022, he was living in Charlotte and driving to a massive studio space in South Carolina loaded with fog machines, projectors, cables, and body-tracking tools. It wasn’t a place built for clean results or client work. It was a sandbox, a laboratory, a place designed entirely for improvisation. Wires sat coiled in corners. Gear was always half-set-up, half-torn-down. Everywhere he looked, something invited interaction.

“I had it set up so I could walk in with my eyes closed and find something to play with,” Hall says.

That sense of playful chaos became his curriculum. Rather than following tutorials or planning shoots, he learned by touching everything, breaking things, rearranging tools, and following whatever sparked attention. He recorded constantly, not with the goal of making polished work but simply to document discovery.

This rhythm of exploration unexpectedly pulled him toward the art world. As his interactive tests grew more intricate, projections layered onto fog, sensors responding to movement, visuals bending in real time, museums and galleries began reaching out. The invitation into that space felt surreal, and in hindsight, Hall recognizes just how little he understood the ecosystem he was stepping into.

“I didn’t really understand what it meant to be an artist or how social media worked. I’ve just always loved making things, recording videos and taking photos.. and then keeping them to myself in Google Photos,” Hall says.

That instinct to hoard work quietly would eventually become the opposite of how he now operates. The studio that once held thousands of unseen files was the birthplace of the mindset shift that would come years later, one in which showing up online would become part of the work itself.

Learning How to Show Up Online

By 2025, Hall realized that making work wasn’t enough. The digital landscape rewarded presence, not perfection. So he approached social media with the same intensity he once applied to his studio, treating it as a space to experiment relentlessly. He set a pace most people would consider extreme, but to him it felt natural.

“I started posting almost ten times a day, every day,” he says.

His feed became a living sketchbook. He posted new art, old experiments lost in his Google Photos archive, off-the-cuff ideas, odd textures, behind-the-scenes moments, anything that carried a spark. The volume was staggering, but it revealed something important: patterns in what people connected with, and the freedom that comes from not overthinking the outcome.

Among this rapid stream of content was the resurrected laser clip. When he first shared it back in 2022, it hardly registered.

“It might have gotten 15 likes,” Hall recalls.

But in 2025, it hit differently. The internet began filling in details that weren’t in the video, inventing narratives, debating the danger, and transforming the sensor damage into a symbol of artistic dedication. It became a form of collective conversation, a moment in which viewers were not just watching but participating.

“If you can give people something that they can use to create their own story with their own imagination, it creates really interesting engagement,” Hall explains.

It wasn’t the laser. It wasn’t the perfect circle. It wasn’t even the glitch. It was the invitation, open and suggestive. The caption turned the experiment into a story, open to the viewer’s interpretation.

Risking the Phone, Saving the Vision

Hall has owned nearly every type of high-end camera one could want, from the Blackmagic Ursa to the Fuji GFX100S. But despite the sophistication of those systems, the camera he reaches for most often is his iPhone. It is the device that best matches the speed, spontaneity, and risk tolerance of his creative process.

“I vividly remember when the iPhone 14 became my favorite camera,” he says.

The reason goes beyond convenience. The phone liberates him from caution. It becomes a tool he doesn’t have to protect, enabling experiments he would never attempt with a more expensive setup.

“I would NEVER walk in front of a laser with my GFX. That would be insane. But with my iPhone, with Applecare, I’m willing to risk it all,” Hall says.

This philosophy of welcoming unpredictability and letting accidents happen has become central to his aesthetic. Instead of exporting pristine digital renderings, he often chooses to film his computer screen with his phone, capturing reflections, monitor flicker, and small imperfections that feel tactile and alive.

“For some reason that’s more of a vibe to me,” Hall says.

In a moment when digital tools can manufacture endless perfection, Hall is drawn to the fleeting human element, the accidents and textures that cannot be replicated.

“I’m more interested in capturing a human element that only exists in the moment,” he explains.

An Artist Between Worlds, Building a New One

Today, Hall’s work exists in a space where physical installations and the videos of those installations carry equal weight. A fog sculpture is not complete until he films it. A digital effect becomes meaningful only when it interacts with the real world. The art exists in the tension between mediums, and the viewer contributes by interpreting what they see.

This philosophy is driving his most ambitious project to date, a world-building endeavor titled Cowbone.

“I’m currently working on a project called Cowbone where I plan on incorporating everything I’ve learned from social media, photography, filmmaking, and interactive media to create an immersive storytelling experience that spans across digital and physical mediums,” Hall explains.

Cowbone functions like a universe rather than a single artwork. It unfolds across formats, platforms, and experiences, mirroring the way Hall blends mediums in his broader practice. It is a project shaped by years of tests, mistakes, viral anomalies, and curious discoveries.

The Shot That Burned a Sensor, Not a Bridge

Alexander Newman Hall’s creative philosophy is built on constant risk, curiosity, and output. The laser video was never engineered for virality. It was not crafted to hack an algorithm. It was simply an experiment brought back to the surface at the right time with the right framing. And that simplicity resonated far more than any polished production.

The sensor burned. But the story grew. And for Hall, the lesson was not about danger or spectacle. It was about the unpredictable power of sharing work freely and without hesitation, trusting that an audience will find meaning in the spaces left open for interpretation.

Image credits: Alexander Newman Hall