Stanford researchers are bringing a sci-fi vision to life aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

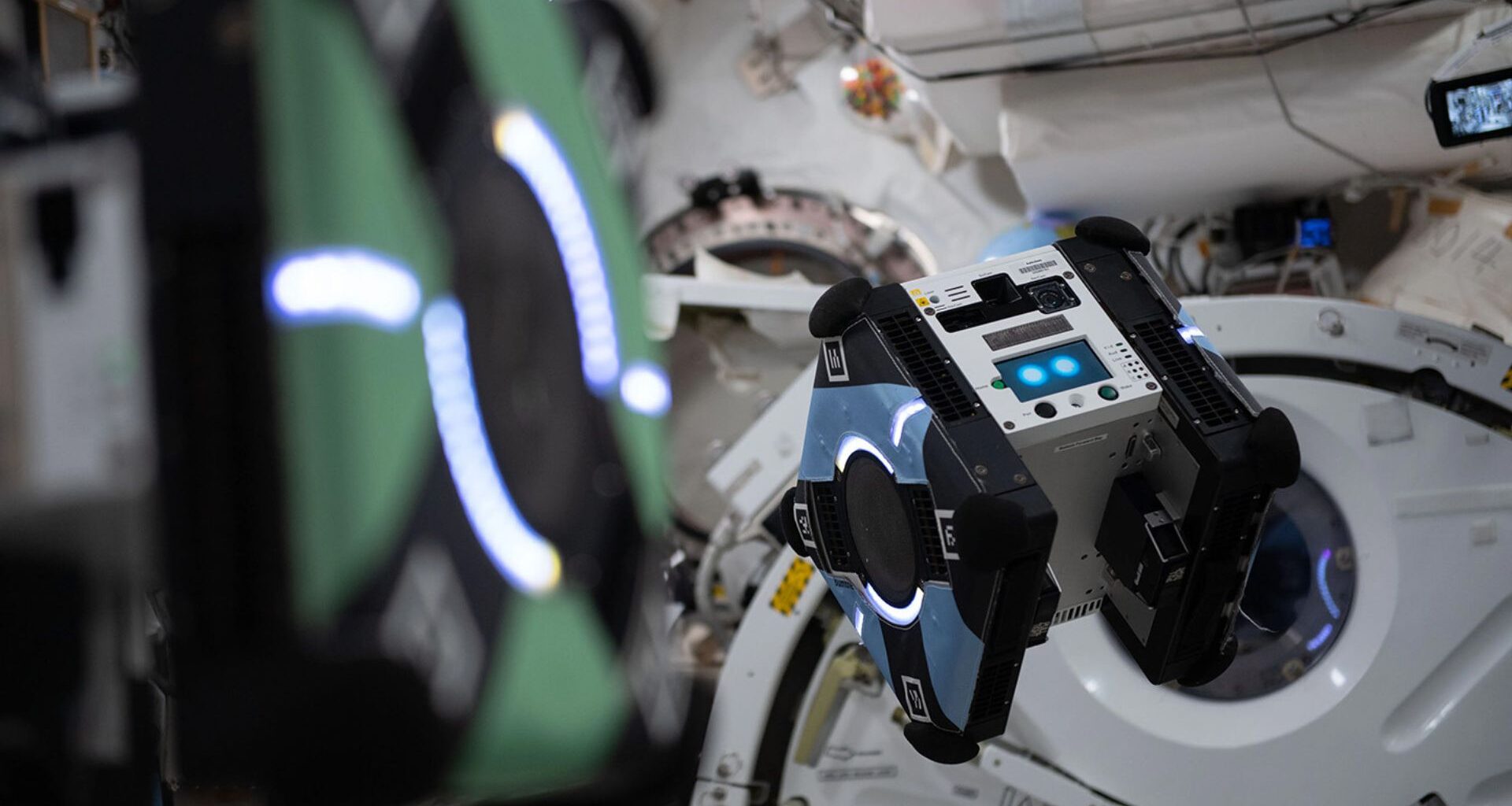

They have become the first to demonstrate that AI-based control can guide a robot autonomously in space. The research focuses on Astrobee, a cube-shaped, fan-powered robot designed to float through the ISS’s tight, equipment-filled corridors.

The system enables Astrobee to navigate complex modules, avoid obstacles, and perform tasks such as leak detection or supply delivery—potentially freeing up astronauts’ time and opening new avenues for robotics-driven space exploration.

“It shows that robots can move faster and more efficiently without sacrificing safety, which is essential for future missions where humans won’t always be able to guide them,” said Somrita Banerjee, lead researcher who conducted this work as part of her Stanford PhD, in a statement.

AI guides Astrobee

The achievement represents a significant step in space robotics, where conventional autonomous planning methods used on Earth are often impractical due to limited onboard computing resources and stringent safety requirements.

“Flight computers in space are far more resource-constrained than terrestrial robots, and uncertainties, disturbances, and safety demands are much higher,” said Marco Pavone, associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford and director of the Autonomous Systems Laboratory, in a statement.

The research team developed a route-planning system for Astrobee, the ISS’s robotic assistant, that leverages sequential convex programming—a method that decomposes complex trajectory planning into smaller, tractable steps while guaranteeing safety and feasibility. However, solving each step from scratch can be computationally intensive and slow.

To accelerate this process, the team integrated a machine-learning-based model trained on thousands of previous path solutions. The model identifies recurring patterns in corridor layouts and obstacle locations, providing a “warm start” for the optimizer. The approach allows Astrobee to generate safe, efficient trajectories more quickly, without compromising constraints. “Using a warm start is like planning a road trip with routes driven by others before refining for speed and efficiency,” said Banerjee in a statement.

According to the team, the integration of optimization and machine learning marks the first instance of AI-assisted robot control aboard the ISS, enabling faster, safer, and more autonomous operations crucial for future deep-space missions.

Autonomous space robotics

The team trialed the AI system before deploying it in space on a specialized NASA testbed designed to simulate partial microgravity. A robot similar to Astrobee floated above a granite surface, supported by compressed air to mimic the frictionless conditions of orbit. This setup enabled the AI to navigate while encountering virtual obstacles, refining motion planning without risking collisions.

During the ISS experiment, astronauts performed only minimal setup and cleanup, while the AI system operated autonomously for 4 hours under remote supervision. Ground operators relayed commands to the robot, specifying start and end points, obstacle configurations, and testing both conventional “cold start” planning and AI-assisted “warm start” planning. Each trajectory, lasting over a minute, was run twice, allowing a direct comparison of planning efficiency.

The results demonstrated that warm-start planning significantly accelerated trajectory computation, reducing planning time by 50–60 percent, particularly in complex environments with tight corridors, cluttered spaces, or rotational maneuvers. Multiple safety measures, including virtual obstacles, backup hardware, and abort capabilities, ensured risk-free operation. Following the experiment, the AI system achieved NASA Technology Readiness Level 5, indicating successful testing in a real operational environment.

According to the team, advances in safety-focused, mathematically grounded autonomy pave the way for robots to operate more independently, supporting crewed missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond by allowing astronauts to focus on higher-priority tasks while autonomous systems handle routine or hazardous operations.

The details of the Staford team’s research are available on arXiv.