Almost everyone who worked on it walked away from production uttering “Never again.” Yet it’s become so beloved that even Ron Howard and Jim Carrey are considering the possibility of a sequel.

Video: Universal Pictures

It is the strangest movie. When Ron Howard and Jim Carrey teamed up to make a live-action feature-film adaptation of Dr. Seuss’s beloved children’s book How the Grinch Stole Christmas, some might have expected a straightforwardly heartwarming family picture, but the resulting 2000 film was nothing of the sort. Howard had been a fan of the book and the 1966 half-hour animated special, but he wasn’t initially interested in making another kids’ fantasy. (His previous film had been the topical reality-TV satire EdTV; his next would be the Oscar-winning biopic A Beautiful Mind.) And though he was known as a blockbuster funnyman, Carrey had entered a more dramatic phase of his career with acclaimed (and Method-y) roles in The Truman Show and Man on the Moon; his next would be The Majestic.

Director and star leaned into the tonal challenges inherent in the project: To translate Seuss’s world into live action meant truly bizarre prosthetics and costumes, ornately angled sets, and a style of humor that mixed childlike innocence and surreal irreverence. The CGI takeover of Hollywood had begun, but the vast majority of this film was practical, including Carrey’s incredible Grinch costume, somehow both cute and deeply unsettling, designed by special-effects legend Rick Baker to give the actor maximum expressiveness. The challenges faced by this project were epic. There was Dr. Seuss’s widow, determined to preserve her late husband’s work. There were nervous-breakdown-inducing makeup and prosthetic challenges. There was the massive cast, all decked out in single-use foam costumes that made it hard to move, hard even to go to the bathroom.

Howard admits today that had he made the film several years later, he probably would have used a lot more CGI. Indeed, How the Grinch Stole Christmas is a picture that could have only existed at its particular moment in time on multiple levels. It features Carrey in peak form, combining the elasticity of his comedy with an undercurrent of self-aware brooding. The movie is hilarious, fun, disturbing, perplexing, exuberant, exhausting. Critics were not kind, but the film immediately prevailed at the box office, networks fought over its TV rights, and it eventually morphed into a seasonal streaming must-play. (It’s back in theaters now for its 25th anniversary and there’s a new 4K out this year, too.) Today, despite the fact that almost everyone who worked on the movie walked away from its chaotic production uttering “Never again,” they’ve begun teasing the possibility of a sequel.

Ron Howard and Brian Grazer belong to the generation of kids who first grew up with Dr. Seuss’s children’s classic, which was originally published in 1957. Howard also recalls that he and his children regularly watched Chuck Jones’s 1966 half-hour animated version, featuring the voice of Boris Karloff. In 1998 it became known in Hollywood that Audrey Geisel, Dr. Seuss’s widow, was ready to sell the feature-film rights to the book. There was an immediate rush to try and acquire them. But Geisel was highly protective of her husband’s work and legacy, and she wasn’t ready to give the rights to just anyone who came charging in with a pile of money.

Jim Carrey on the set of How the Grinch Stole Christmas.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Brian Grazer (producer): The lawyer for Audrey Geisel said, “We’re not going to just sell it. We’re going to create an auction where you have to audition with Mrs. Geisel.”

I was chosen by Universal to be the representative of their studio. I took the advice of one writer who had this whole take on it. We saw Audrey Geisel, and she heard it, and I was told it didn’t work for her. I begged, “I need another chance to talk to her.” Because I did have another taker, but it wasn’t what I’d presented. They said, “No, you’ve had your chance.” I said, “Well, but Ron Howard is willing to come.” That made a big difference.

Ron Howard (director): The reality is that I’d made two films aimed at young audiences, and they were both incredibly difficult. First was a TV movie, Through the Magic Pyramid, a time-travel story about a little kid who goes back and hangs out with young King Tut, made in 19 days on a very tight budget. And then Willow was the toughest thing I’d ever made, incredibly challenging and exhausting. I was proud of it, but I wasn’t really looking for another family-friendly entertainment or a fantasy of that type.

Grazer: I was able to convince Ron to see Audrey Geisel. He said, “I’ll come, but I don’t want to direct. Don’t say I’m the director.”

Howard: I was on a plane, next to my wife, Cheryl, coming out to LA. She said, “The story is all about commercialism. And if Whoville has just gotten ridiculous, maybe Cindy Lou could have an attitude about that. So in a way, it could be an affirmation story for her and a lesson for all the Whos.” I thought, “Oh, what if that’s the third act? What if we deal with this commercialism, deal with his alienation,” which was a very Seussian theme.

Grazer: So we pitched it, and Audrey just assumed Ron would direct.

And Audrey said, “I really want Jack Nicholson to play the Grinch.” I said, “Jack Nicholson is amazing, but I don’t think he has the qualities of what we’re looking for. The Grinch is crabby and mean, and you have to forgive him for being crabby and mean. He has to have a lot of innocence.” And she said, “Who would you want?” I said, “The only person I would do it with is Jim Carrey, no other actor.”

Which I really believed. But I just kind of threw his name out. I didn’t ask him. I was making Liar Liar at the time, so I was working with him. This was also around the time I was going to do A Beautiful Mind, and Jim very much wanted to do A Beautiful Mind, a movie with drama and gravitas. But I was already pursuing Russell Crowe, and I didn’t want to tell him. So I’d always veer back to the Grinch. I’d go, “No, no, no, you’re so much better for this. This would be great.”

Jim Carrey (The Grinch): Ron and Brian came to me and said, “Would you be interested? And if so, would you meet with Audrey Geisel?” I went to the Peninsula Hotel, and I met with Audrey and told her how much Dr. Seuss meant to me growing up and how important it was to pay homage to that. Suddenly, I ended up doing the Grinch for her across the table, actually doing the face. I didn’t have any makeup on. I just gave her one of those, “I musst find a way to stop Christmas from coming.”

The voice — there’s a touch of Boris Karloff in there. He made such an impression on me. But mostly, the voice came from the interior. I ended up gritting my teeth to the point of cracking them. He’s a character with a heart-withering sense of abandonment and alienation that has infiltrated his entire being. He resents anyone who has joy in their life. I physicalized his arrested development into this depiction of a 7-year-old who’s having a tantrum stomping off to his room.

Grazer: I said, “Ron, you have to say you’re going to direct it. If you decide after we do the script that you don’t want to do it, we’ll figure a way out. But for now you have to be the director. I have to get it.” He said “yes”; he would play that little game with me.

Howard: My litmus test when I’m on the fence about something is, “Will I be upset if someone else gets to direct it?” And it was a big screaming “yes.” Because Jim just had such an immediate sense of how to bridge that tone between comedy, pathos, and the edge and rage that the Grinch brings to the piece. That was irresistible.

The original Grinch story is spare and short. In order to make it work as a feature film, Howard needed a screenplay that would populate this world, flesh out the story, and develop the characters. The film also needed to be genuinely funny and irreverent in order to appeal to both kids and adults. Audrey Geisel reportedly intervened at several points during the initial writing process because certain gags were a little too risqué for the family-friendly appeal of the original. But Howard and Carrey persisted in their efforts to give the film a unique, offbeat tone. This required the contributions of quite a few screenwriters and ultimately resulted in a Writers Guild arbitration that proved heartbreaking for some.

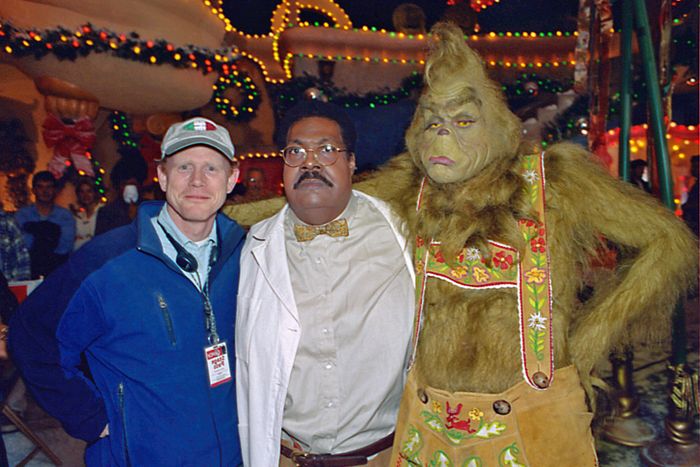

Ron Howard, Jim Carrey, and Jim Carrey’s body wig on the set of How the Grinch Stole Christmas.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Howard: So we had our initial writers, Jeffrey Price and Peter Seaman, who broke the story, and then we had Alec Berg, Jeff Schaffer, and David Mandel, who were Harvard Lampoon writers and fresh off Seinfeld. They weren’t credited, but they did extensive rewrites.

David Mandel (co-writer): When Seinfeld ended, we signed separate television deals, Jeff and Alec together with DreamWorks and me with Touchstone, but nobody was getting any TV on the air. Even though we had these television deals, the three of us were very in demand on comedy movies to bring a bit of what they used to call “Seinfeld smart” humor to the scripts.

Alec Berg (co-writer): Our thing was basically the two-week rewrite where we just did comedy punch-ups. God, we worked on so many movies.

Jeff Schaffer (co-writer): This was different because this was an honest-to-God rewrite. “Here’s a script. It’s not working. We have Jim Carrey. We’re close.”

Berg: We came in at a pretty late stage. It was fully cast. They were building sets.

Mandel: We had a very funny meeting where Judd Apatow was there. Jim didn’t know us, so Judd vouched for us. Then we sat with Jim and went line by line through the script. When all was said and done, we moved to the stage.

Schaffer: They taped out the Grinch’s cave on this empty stage. We went through and did his scenes and improvised with him and added that to the script we had already rewritten. Because Jim, pre–Andy Serkis and digital dots and all that, was going to be in this suit that was super-hot with these green eye contacts that were going to cause him so much pain. He’s like, “I’m not going to be able to improvise when I’m in this suit.”

Carrey: Comedy is a very mechanical thing in certain respects. It has to work timing-wise. It has to tickle your fancy. It has to surprise you. A bit like being a magician, where you come in with the twist or whatever it is, and it has to be exact. If you do it well, people take for granted that it was just off the cuff. Because you’re making it live in the moment.

Berg: His dedication to it was unbelievable. He might’ve driven some people nuts by just how obsessive he was, but for us, it was gold to be working with somebody who cared that much and was that intensely focused on getting everything right.

Mandel: I remember, in the cave, he wanted to know there are 37 stairs from level one to level two, and he wants to know he’s going to walk up six stairs, then he’s going to turn and yell at her, then he’s going to go up another three, then he’s going to come back.

Schaffer: We even wrote Seuss stuff. I mean, the opening narration inside the snowflake, that’s all us. That’s not even Seuss. We were writing Seuss stuff to connect things, because obviously the story that Dr. Seuss wrote is pretty short.

Berg: It’s a really tough balance, right? Because that source material is so revered, so people are like, “This is what the Grinch is, and this is not what the Grinch is.” How much do you honor it, and how much do you play with it and satirize it and goof on it a little bit?

Schaffer: For us, it’s two things. It’s embellishing all the characters, especially the Grinch, and getting all of that fun. And then, yeah, we’re going to put stuff around the edge, something for the adults. We can’t help ourselves. Like that Ice Storm thing. I distinctly remember we added the key party. And then “What if it’s a cash bar?” “I’ll just grab some popcorn shrimp.” All that dialogue.

Mandel: His day planner, like, “What am I supposed to do today?” “Stare into the abyss.”

Berg: “Wallow in self-pity.” “Dinner with me. I can’t cancel that again.” There was also a thing where he pulled a tablecloth off a table and all the stuff stayed in place, and he started to walk away, but then came back and messed it all up. That was the joy of the movie, the tone of that character with all that self-loathing.

A Little Looping Story

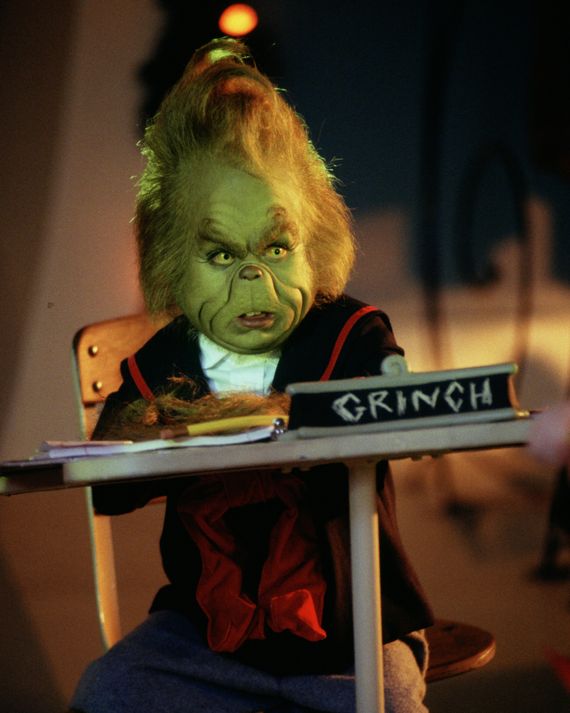

Jim Carrey, living life as the Grinch.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Schaffer: Jim’s performance is so incredible, especially when you take into account the layers of makeup he’s in. It was so fun watching him do it in a T-shirt and shorts, but watching it come to life was an amazing process. We learned a lot from Ron about listening to actors and just how important that was.

Mandel: Ron had that level of openness. “Best idea wins.” He allowed us to really be his collaborators, both on the front end with the script and then later in the edit room. He trusted us enough to do the looping, which was wonderful and wild.

Carrey: It’s the most looping I’ve ever done. Because of the combination of me breathing through my mouth and the wind fans that were blowing the snow around, I pretty much had to loop the entire movie.

Schaffer: One thing I remember at the looping very specifically was Jim had been smoking when he did the shoot and he had stopped smoking, and he was so worried that now that he had stopped smoking, his voice sounded different.

Mandel: He felt it wasn’t deep enough the way it had been when he was a smoker. So he was trying to smoke to get his voice back where it was.

Carrey: That could be true. I’ve lived a lot of life. Some of the details have slipped my mind.

Mandel: Arbitration was a very strange thing because we were originally given credit.

Berg: The way it works with the Writers Guild is the studio or the filmmakers propose a credit. And what they proposed, which was fair, was story by them and then screenplay by all of us.

Mandel: The first teaser trailer has all our credits on it.

Berg: Any writer who’s involved has the right to ask for arbitration. But we were told the arbitration-request period had elapsed, and these credits were now official. “Holy shit, this is great. We got shared screenplay credit on this massive movie. We’re so psyched.” Ten days later, we are told that Seaman and Price had changed agents, and their new agent had been sent the notice of tentative credits. But the agent who represented them when the Grinch deal was done should have been notified of the tentative credits. So even though the time had elapsed, it turned out Seaman and Price had been improperly notified. And it went to arbitration, which is a real spin of the wheel. There were three people who read the different drafts; two sided with them and one sided with us.

Mandel: A lot of rewriters come in, and the first thing they do is change the names of the characters, so they are creating “new” characters. Then they can argue in their arbitration that they created a new character. And we never did that.

Schaffer: I distinctly remember the tipping reader said, “Rewriters should never get credit.”

Mandel: So the credit was taken away from us! Obviously, we were not happy. We are really fucking proud of that work. That Jim stuff holds up like anything today, and we wrote almost every line of that dialogue. And let’s be honest, those residuals would’ve really been something. Ron and Brian have always been incredible, Ron especially, about our contribution. He’s gone out of his way to credit us.

Berg: Also the way that Writers Guild arbitration process works is that if you arbitrate for credit and you don’t get credit, the Writers Guild forbids what they call compensatory credits. You can’t even get a special thanks or whatever. Jim Carrey’s dentist has a credit on this movie, and we don’t.

Schaffer: I want to say something: He’s a fucking great dentist.

Carrey: Well, somebody has to make the veneers. But, oh my God, no, those writers deserved a lot of credit, for sure.

Legendary makeup artist Rick Baker (who already had five Oscars and would win another for this film) was hired to create a Grinch mask and costume for Carrey. But Carrey’s elastic facial expressions were a huge part of his star power. How, then, would his face be visible underneath all that makeup? The solution was an elaborate prosthetic that would prove insanely difficult to apply. It almost drove the actor crazy, which also meant that it almost drove the people working to put it on him crazy.

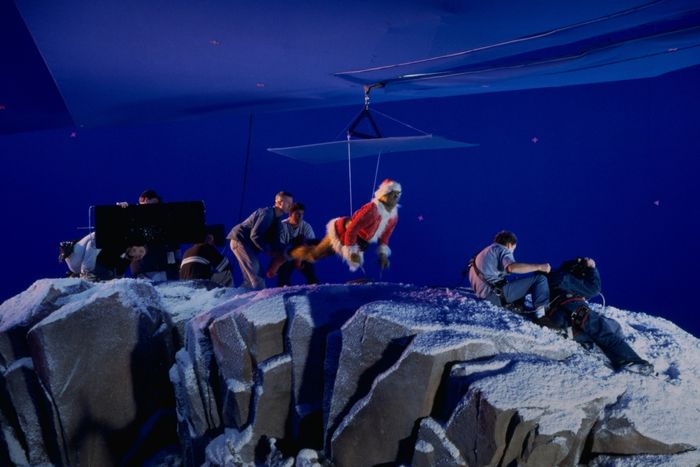

Jim Carrey suspended in full Grinch costume, perhaps realizing what he has brought upon himself.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Carrey: I went into Rick Baker’s shop. I’d always revered him. He’s an absolute genius. We got in the makeup chair, and I said, “I want to be the Grinch from the book.” We started experimenting with just painting my face. “No, I don’t want to be one of the cast members of Cats. I want to be the Grinch.” And, of course, Rick Baker did a masterful job.

Rick Baker (special makeup effects): I did some designs, and I did a sculpture knowing what the problems would be because I’ve worn a lot of makeups myself. If you do a nose that’s high up on the person’s head, breathing through your nose is difficult. Talking with that is difficult. So I did kind of a compromised sculpture first, where I put the nose down where Jim’s nose actually is, so he could breathe through the nose holes, and it was a little more like a dog.

Brian and Ron signed off on it, but afterward, I thought, It’s not as cool as it should be. So I did a makeup on myself of what I thought the Grinch should look like, and I videotaped myself performing in it, and sent the tape to Ron and Brian.

Carrey: When it came down to actually designing the Grinch to look like the Grinch, they had to put the tip of my nose on the top of the bridge of the Grinch’s nose. So, all of the rest of it was covered and I couldn’t breathe through my nose, and they had a real problem trying to get holes in the mask that could allow me to breathe through my nose. Ultimately, I ended up mouth-breathing through the entire movie.

Baker: The studio said, “We’re paying Jim $20 million, and we want to see him. Just paint him green.” But it’s not How the Green Jim Carrey Stole Christmas. It’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas. He should look like a fantasy character.

There was a popular movie website at the time, Ain’t It Cool News, and the guy who ran it was a fan of my work, and I contacted him. I said, “Listen, Universal wants to paint Jim Carrey green. I feel it’s a major mistake. I did a test on myself of what I think it should look like. Can you somehow say that you saw this test and that Universal is making a major mistake and they don’t know what the fuck they’re talking about?” And he did. And it was outrageous responses from everybody. “What the hell is wrong with these people at Universal? I don’t want to see green Jim Carrey. I want to see a Grinch!” Blah, blah, blah. So they finally caved in.

It’s funny because Ron called me up and he goes, “This guy somehow saw the video.” And I said, “Well, I only sent a copy to you and Brian. I’m not sure how he saw it.” I usually don’t lie, but I did for the sake of the movie.

Howard: When we were rehearsing scenes and rewriting them, Jim was just in his T-shirt. But he was sweating like an NBA player in a workout. So you can imagine what it was like when he got that full body suit on.

Bill Irwin (Lou Lou Who): Jim Carrey is a very generous wacko. There is a generosity of spirit at the same time that he’s a warrior comedian. He knows prisoners can’t be taken, and he’s got to focus on the madness of his character, his creature.

Howard: Jim was insistent on the look. Some things made him pretty uncomfortable, but he was determined. There was no compromise of the look that he would embrace.

Carrey: The suit was made of unnervingly itchy yak hair that drove me insane all day long. I had ten-inch-long fingers, so I couldn’t scratch myself or touch my face or do anything. I had teeth that I had to find a way to speak around, and I had full contact lenses that covered the entire eyeball, and I could only see a tiny tunnel in front of me.

Howard: Some people, when they learn to scuba dive, find that they just can’t wear a mask underwater. A kind of claustrophobia kicks in. And I think for Jim, the contact lenses were doing that.

Carrey: I’d be on top of a 50-foot mountain walking around with this ridiculous costume on and hoping I don’t go off the edge accidentally. At the same time, I had to give the audience a sense that, Hey, he’s having fun in that thing, and we’re going to have fun with him. There was a certain buoyancy that had to come with the character.

Baker: Jim is a tortured soul. He obsesses about things. He was very, very difficult to deal with when he was the Grinch. But it was probably part of his process. He was great in the movie. I know in the Andy Kaufman movie when he was Tony Clifton, he stayed in character. So he’s kind of a Method actor.

Grazer: We said we could do the green eyes digitally. He didn’t want to do that. He wanted to have green eyes. They were like Frisbees in his eyes. He was in so much pain.

Carrey: It was something that I asked for that I can’t blame on anyone but myself. You’ve got to be careful what you ask for. You don’t think about it when you see an actor do a part that is about excruciating pain or whatever. But that actor has to live in that feeling. They don’t just go home and suddenly stop feeling it.

Howard: Jim started having panic attacks. I would see him lying down on the floor in between setups with a brown paper bag. Literally on the floor. He was miserable.

Carrey: The first day in makeup took eight hours. And I went into the trailer and asked Ron and Brian to come in, and I told them that I wouldn’t be able to do the movie and I was quitting.

Howard: He was ready to give his $20 million back! I mean, he was sincere.

Grazer: “I will give all my money back. I’ll pay interest. But I quit.”

Howard: So Brian found a guy who trained the military on enduring imprisonment and torture. Because, literally, Jim was about to leave.

Grazer: I said, “Listen, you can quit on Monday, but just spend time with this guy on the weekend.”

Carrey: Richard Marcinko was a gentleman that trained CIA officers and special-ops people how to endure torture. He gave me a litany of things that I could do when I began to spiral. Like punch myself in the leg as hard as I can. Have a friend that I trust and punch him in the arm. Eat everything in sight. Changing patterns in the room. If there’s a TV on when you start to spiral, turn it off and turn the radio on. Smoke cigarettes as much as possible. There are pictures of me as the Grinch sitting in a director’s chair with a long cigarette holder. I had to have the holder, because the yak hair would catch on fire if it got too close.

Later on I found out that the gentleman that trained me to endure the Grinch also founded SEAL Team Six. But what really helped me through the makeup process, which they eventually pulled down to about three hours, was the Bee Gees. I listened through the makeup process to the entire Bee Gees catalogue. Their music is so joyful. I’ve never met Barry Gibb, but I want to thank him.

Howard: We also made concessions in the production schedule. This wasn’t as much mental as it was physical because it was destroying Jim’s skin. Medically, it was determined he really couldn’t do it five days in a row. So he would have a day off, or he’d only be off-camera feeding dialogue on Wednesdays.

Carrey: There were a lot of things going on under that suit. It wasn’t a healthy situation, but movies are that way. You do it because the end product is going to be something special. Kazu Hiro was the one that applied my makeup every day, and he did an incredible job of painting my face.

Baker: My poor makeup artist was on the verge of a complete mental breakdown because it was so difficult. He wanted to quit. I went into Jim’s trailer, and I told him, “We’ll get somebody else, and it’s going to look half as good and take twice as long.” And he goes, “Well, you don’t understand what I’m going through.” I said, “I played King Kong in the Dino De Laurentiis King Kong. I wore hard scleral contact lenses that I put in, in the morning, and I took them off at lunch and put them back in and wore them to the end of the day. I had a suit that weighed 50 pounds made out of bear hides and six inches of foam rubber. I had a bundle of cables that came out the back of my neck and ran through the suit out my leg and had to drag around everywhere. I would bleed every day from the mechanism in the face.” I said, “You’ve got it easy because I made a lot of changes in the way the makeup works so they would be more comfortable for you.”

After that, Jim became a lot better. But having said all that, what I really respected about Jim and where I think the torture really came in was the number of days. He was 92 days in makeup, something like that, which is like a record.

Howard: It was remarkable, because there were many times when I knew he was exhausted, but he’s one of these actors, a little like Charlie Chaplin is reported to have been, who is such a perfectionist that he would want to go take after take after take. There were times when he was running on fumes, and yet it wasn’t until take 20 or 22 that he felt comfortable moving on.

Baker: I did appreciate, even as tortured as he felt, if he didn’t think he gave a performance that he wanted, he would do another take and another take. He was fantastic in the film, and I don’t think anybody would’ve been better. I just wish it was a little easier to deal with him.

Carrey: I need to find an emotional connection. As time went on, I’ve learned how to not only do the comedy, but for there to be a real organic emotional connection bubbling up underneath. That informed my work in The Grinch because you really feel his transformation. There’s been parts that I’ve turned down because I didn’t want to be in that feeling for one reason or another. But the makeup difficulties helped me in a way. It definitely put me in a solid place. The overall, arcing motivation for me was a good one. I knew that people were going to find it joyful. Kind of.

The Young Grinch

Josh Ryan Evans as the Young Grinch.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Howard: Josh had great energy, was hardworking, loved it, understood it. Smart kid. I think he was 17 or so. The amount of time that he needed to be in makeup and so forth, we needed somebody who could work longer hours, so there was a practical side there. But also I wanted him to be hipper and more mature than the other kids. And maybe as a little person, he understood feeling like an outsider. He brought a lot of soul along with great comedy timing to those scenes. I was really sad that we lost him.

Carrey: Josh did a wonderful job, and I wasn’t even aware that he had passed on for years. I had no idea. So that was sad, but boy, he’s absolutely fantastic.

Baker: I really liked working with Josh. He had had open-heart surgery before. He had a big scar going down the middle of his chest. I really enjoyed him in the makeup. And I enjoyed sculpting and making the baby puppet Grinch.

Baby Grinch.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Howard: That was a very important aspect of my concept, that we would take a look back at the Grinch and his alienation and isolation and comedically deal with it. And Josh totally understood it and had great timing. Jim worked with him a bit so he could emulate some of Jim’s moves and the attitude. Those scenes were some of my favorites because we were liberating ourselves from the book and creating something I connected to. I knew it was going to surprise audiences, but I thought it spoke to the character that Seuss had created.

Baker: It never ended up in the film, but there was actually a teenage Grinch too. I made him a 1950s juvenile delinquent Grinch, with a pompadour hairdo and a little cigarette pack rolled up in his sleeve on his arm. But yeah, that never happened.

How the Grinch would look and act was just one part of the equation. The lead role opposite him would go to a 6-year old actress making her film debut. And she would be in fairly heavy makeup herself, alongside all the other characters populating Whoville. Beyond the issue of what the Whos would look like, there was the added question of how they would move.

The many makeup stations on the set of How the Grinch Stole Christmas.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Taylor Momsen (Cindy Lou Who): I started doing national commercials when I was 3, and Grinch was one of the first major films that I auditioned for. I remember the phone call when I found out I was booked for the part because I was back home in St. Louis and driving with my mother. We were just giddy with excitement. I was either 5 or just turned 6. By the time the movie finally came out, I was 7.

Howard: When you’re casting kids, first of all, girls are ahead of boys. They get it sooner. A 6-year-old girl, if they’re inclined to be able to do this sort of thing, they have great imaginations and their playacting is very real, so they can connect with the ideas. And Taylor just had it. She understood it. And she was very well prepared.

Momsen: I couldn’t really read yet when I was shooting Grinch, so someone had to read me the script, and that’s how I memorized all the lines. But they read the entire script, not just Cindy’s parts, so I had memorized the entire film. When I was shooting with Jim, Ron would call cut and he’d go, “Taylor, you’re doing it again.” “What am I doing?” “You’re mouthing Jim’s lines. It was like a whole song in my head.

Howard: It was a hard role. She was kind of a secret weapon. She was such a perfect straight man for the Grinch, a perfect foil. And Jim was great with her.

Momsen: I never knew what Jim looked like, because I never saw him outside of the makeup until the premiere, and I was too young for his films. So to me he was just Jim who looked like the Grinch.

Carrey: It’s funny, I’d never really thought about that. Because I got there super-early, before anybody else got there. She never saw me till the premiere when someone had to point me out and say, “That’s Jim Carrey.”

Momsen: And he was incredibly protective. That’s what I remember. Jim was very, very protective of me on set as a person, as a kid, always looking out for me, checking in, making sure I was okay, because he was very animated, very over the top.

Carrey: Of course, I’m jumping around her like an out-of-control monster, so I had to let her know that I’m going to be doing some monstrous things, but I’m not a real monster.

Momsen: I remember when we were shooting the scene coming down the mountain on the sled. It was this real sled that was up on a giant spring that was being controlled and moving from side to side, very aggressively. Jim is leaning over and being extravagant Jim. There was a moment where I almost fell out of the sled, and he freaked out. He called cut and started checking in on me. I was having a great time. I was laughing; I wasn’t thinking about the fact that I just almost fell very high off the ground.

I always felt really safe with Jim. I liked being around him. At such a young age, to watch an artist who is that serious at what they’re doing even while playing this very over-the-top character, it was clear to me how much he was putting into it and how much of an artist he was.

Carrey: As soon as I met her, you could just tell right away she was just an incredibly precocious child — smart beyond her years, and her comedy timing was impeccable. A total pro. I don’t think she ever went up on a line or missed a cue or anything like that.

Baker: When I got the call from Brian Grazer about doing a live-action feature of How the Grinch Stole Christmas, one of the first things I said was, “I don’t know what the hell the Whos are, and I don’t know what to do with them.” In the book, they almost look like insect people. I said, “When you start changing a human face around, it can get grotesque very quickly.” I asked, “What about Cindy Lou? Are you going to use a little girl for Cindy Lou Who? Because we can’t put a little girl in a three-hour makeup.” And they said, “Yeah, we do want to use a little kid.” So, I started playing with designs.

Momsen: Rick actually cast my face and I went through that whole process. He has a mold of my baby face still in his house! I was just there for Halloween this year. He has every face of every person he’s ever cast, and so my little face was there too.

Originally, they were thinking about having me in prosthetics, but I think Ron and everyone just collectively decided that that’s too much to put a child through.

Taylor Momsen as Cindy Lou Who.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Baker: I eventually came to the rationalization that the Whos, when they’re younger, their noses haven’t moved up their face like the adults’ noses have. So we went with oversize teeth and long eyelashes, and we painted her nose a little red.

Momsen: Growing up after the film, everyone always asked me about what it was like to have a fake nose, and I didn’t have one. I was going, “That’s my real nose. I swear it’s just blush. But thank you for making me feel self-conscious about my nose.”

Then the teeth really pushed out my upper lip and created an odd face shape. I hated the taste of the glue that they used to put the teeth in, so I never took them out. I ate with them, I talked with them, I went to school with them. They were a part of my face until we wrapped for that evening.

The fake eyelashes were so fun for a girl. That part stuck well into adulthood. It was glam. And the wig itself was incredibly elaborate. Doing this Christmas record I just did, Rick was so kind as to loan me the original wig. When we unboxed that at a photo shoot for the first time in 25 years, it still had the snow on it, which had a very specific scent. All the memories came flooding back.

Howard: We had mission-control school and astronaut school for Apollo 13, and I’d done a version of that for The Paper where we all hung out at the Post and the Daily News just to learn the cadences and the jobs. Same with the fire department on Backdraft. This is in a pre-digital era or 3-D-animation era. We had some CG work that we did — the sleigh zooming down the mountain, and Max the dog getting thrown around was always a CGI Max — but we couldn’t do much digitally with the Whos up close. So I came across a stunt coordinator, who became the second unit director, named Charles Croughwell, famous for doubling Michael J. Fox on all the skateboard stuff in Back to the Future.

Charles Croughwell (stunt coordinator): Ron and I sat down for a discussion about the Whos and what they are. We said, “Why don’t we look at Cirque de Soleil?” I knew the Cirque guys. I said, “Maybe those ones that are not on contract right now, we could get some of them as performers.” There was a guy there, Terry Bartlett, who was an amazing Cirque performer, probably my best friend within that world. I said, “Look, we’ve got all these things that Ron wants to be able to do — walking balls, walking ladders, trampoline work.” We started to incorporate that into a Who school, where everybody could go through their characters. We had an entire stage full of equipment, and anybody could come over at any time.

Momsen: I did go to Who school. I had to go through stunt training because I was doing my own stunts. I had to learn to fly on wires and how to fall correctly onto the pad. I fell through a trap door. I had to slide down a massive slide that you had to climb up using a rope because there was no stairs to it. The only stunt I didn’t do myself was the actual shooting out of the trash can at the end.

Howard: I also cast Bill Irwin and asked him if he would come to Who school. He was one of the great clowns in our history, and he became central in helping build bits with the Cirque people with like wires on big unicycles.

Croughwell: Who school was just an absolute blast. Even if they weren’t scheduled for anything, actors would come and hang out and play on the trampoline or whatever. It was a playground for them while they were getting ready for everything else.

Howard: And we did get sort of a style of walking and movement that we tried to utilize, and a menu of physical gags that we could put in scenes as we began to stage them.

Berg: There was a guy who could fold himself in half and sit in a bucket. We just kept pitching fold-yourself-in-half-and-sit-in-a-bucket jokes. But none of them made it in.

Howard wanted the film to have a self-consciously artificial, almost Expressionist look that would reflect Seuss’s off-kilter designs. That meant entire practical sets built at funny angles, multiple soundstages, a cast of hundreds (all in extremely uncomfortable costumes), and a lead actor on the verge of losing it, resulting in a production that one cast member describes as “a war of attrition.”

Clint Howard and his brother.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Howard: One of the things I did with this film was adopt a style I had never used and I’ve never used it since. But I went back to Don Peterman, who was my cinematographer on Splash and Cocoon and also an Oscar nominee for Flashdance. He did Addams Family Values. I wanted to apply those lens choices and that aesthetic. We were shooting with 14-mm. lenses, which were wide and distorting. I had a camera on an arm that was in movement a lot, especially in the Grinch’s lair, and Jim was so good about spinning and hitting the exact mark so the camera could meet him. He understood exactly what we were going for in a 14-mm., this kind of crazed close-up that would evolve at the end of the camera move.

Rita Ryack (costume designer): For me, Dr. Seuss’s drawing style was so distinctive and energetic and gorgeous. Holiday cookbooks from the 1950s gave me some ideas. I have sketches of the Whos being very simple and wearing things on their heads, like plates of food and lamps.

Howard: Production designer Michael Corenblith came in with a book and said, “I have to figure out how to take this Seussian architecture and build it so that people can actually be on the balcony, and it’ll be load-bearing safe construction. Look at this Spanish architect Gaudi. These are examples of these strange cornerless shapes actually being functional.” He tried to build things so that they were skewed in certain ways to create visual illusions with places for Cirque du Soleil people to gain purchase and lean in slightly strange ways and things like that.

Ryack: All the Whos were kind of furry, so I put them all in mohair sweaters. All of the fabrics were very soft and tactile. When Jim is walking through the town in disguise, he has his cape. That’s not bedspread fabric exactly, but it’s kind of like it. I liked that tufty stuff, and I thought that would move; I did want to try and get some energy into those clothes, to make them Dr. Seuss–y.

A lot of collectors today have gotten in touch with prop master Emily Ferry and me. There are people who reproduce the costumes every Christmas and dress up in the Who costumes.

Baker: The Grinch has a suit of padding that gives him this pearlike shape, a big sticky-outty stomach and sticky-outty bum. It’s lightweight polyurethane foam that we carve into the shapes, and that’s mounted on a Lycra spandex suit. So we slip that on first. Over that is another Lycra spandex body stocking that we made that’s dyed Grinch skin color. That’s the hair suit, where the yak hair is tied. It’s a body wig, basically. It’s the way wigs are made with a little ventilating needle and each hair is tied twice into the spandex so it doesn’t come undone. It’s six months of work for one body suit. And then we had about 300 custom-made wigs.

Momsen: I was wearing six pairs of tights at the same time. We had the Who pads, which made your body that weird Who shape. Garters and socks on top of tights and pads inside your shoes to make your toes curl up, and regular underwear, bloomers over the underwear, crinoline, another layer of crinoline. To get dressed took three people and a long time. And without fail, every time I was ready, I then had to pee.

Croughwell: One day we were on the mountain and there’s snow, which is like soap. And one of those soap bubbles got in behind one of Jim’s lenses one day and was driving him nuts. I was with my daughter, who was 5 at the time, who used to play with Taylor. Jim came in, and he’s just walking by us, the same old Jim that he was every day. He goes, “You might want to take her out of here. Probably not a good thing for her to hear what I’m going to have to say.” He just kind of had a meltdown moment there. But the fact that he stopped and said he was concerned about her tells me everything about him.

Carrey: On the day we wrapped, we had a little wrap party, and they put together a reel of all the times I started cursing. Just tied them all together in about a five-minute reel of me cursing a blue streak. That was hilarious.

Irwin: I came in one day, the regular early call, and there was somebody two chairs down who was already halfway into the elaborate three-and-a-half-hour Grinch makeup. And I thought, Oh, some stunt player is going to fly through the air or something. Turned out it was Ron. He showed up hours ahead of his call, got the makeup on, worked through a whole director’s day with that fucking makeup.

Baker: Ron wanted to show compassion for Jim, so we made up Ron, completely suited him up in a Grinch suit, and he directed the whole day as the Grinch.

Carrey: I laughed my head off when I saw him coming through the room. And I thanked him for the empathy. And then he sat in his director’s chair and sweated a lot. Of course he didn’t have the contact lenses that scratch your cornea, but he did his best. He’s just the greatest guy in the world. Ron is somebody you want to do your best for, period.

Ryack: Jim didn’t like wearing that Grinch suit very much, but that was Rick Baker’s problem. I did all the costumes that went on top of it, like the lederhosen and the Hugh Hefner fishnet bathrobe. Those were all really fun. At one point, he said, “Okay, when I’m going to the Whobilation, what am I going to wear?” He was campy too. He had this little dressing montage, and he asked for a beehive. I have a beehive that got made with a veil that’s all covered with bees. I’m looking at it right now, it’s beautiful. I think maybe there’s a full version of the film that has that whole montage.

Howard: I had a blast, but the thing that made the job tough was the scope of the production and the logistics involved. It was one of the few movies I’ve ever made that went over budget. Dogs on wires. Taylor Momsen was fabulous, but she was 6, you know? I was in my golf cart going from one stage to another. At one point, we had three different units shooting over nine stages. One of our soundstages on the Universal lot was entirely dedicated to makeup because you’d have 40 or 50 people in makeup every day and you’d see the Whos on cigarette breaks. Like those corny, Old Hollywood backstage movies where you see people in absurd costumes wandering around having a sandwich.

Irwin: We were on the largest stage on the lot, it’s been there for decades, and that’s where Whoville was set up. My son thought it was kind of like a theme park when he walked in. We did work outside for a couple of scenes. Christine Baranski’s character was putting up the Christmas lights with a machine gun. It was my son’s favorite scene of the movie. That was out on the … hillside, but it was on the lot still, so we would hang out in the old house where Psycho was filmed. We would sit there and watch the shots being set up and then do scenes, but you were breathing actual air, which was bracing.

A Moment for Christine Baranski

Christine Baranski as Martha May Whovier.

Photo: Universal

Ryack: Christine Baranski as Martha May was so much fun to design. I did want to make her kind of couture from the period. I didn’t realize this, but she has such a fan base still. She’s a gay icon, which thrilled me. A lot of people said, “Oh my God, I had my first awakening looking at Christine Baranski as Martha May.” She’s hot. I don’t know if I meant for her to be hot, but the way she worked with the costumes, like when she comes out in her little Santa outfit to decorate, she’s very campy. The machine gun, what an image.

Howard: My mom would actually win the neighborhood contest in Burbank, California, for the best Christmas decorations. It was just lights, but gaudy as hell. I remember one year Dad and Clint were away doing Gentle Ben in Florida, and they were coming home for Christmas. I was old enough that I felt like I should be helping. I was also lazy enough that I didn’t volunteer very early in the process. As it got later, she was more and more desperate to get these lights up, and it was starting to rain. I remember her up on a ladder, trying to string these lights with a cigarette dangling from her lips, in her muumuu. I’m like, “Mom, I can do it!” “No, you can’t!” “Let me hold the ladder!” “No, it’s raining, go inside!”

Ryack: Christine’s Whobilation gown. I always had a thing for those ’50s ball gowns. I found this green tulle fabric for the skirt that had chenille dots on it, so it had some dimension. And the bodice is a red velvet. Then she had the fuzzy marabou red stole and the jewelry and stuff. I dressed her like a doll, I really did. Of course, there’s her satin negligee with all the big white feathers …

Howard: We did want to give Christine a chance to be just ever so slightly more attractive and sexy, and that Who look was a little tough in that regard. So we made her a little more glamorous.

Ryack: There were all kinds of things on the Whos that nobody saw. There was a nurse, and I gave her a necklace with a syringe with blood in it. Very little, quiet, dark things. There was a fisherman, and the actor came in and he had made some fish himself. Those actors really contributed quite a bit. And they all got so close to each other, that was cool. There were marriages among the Whos, reunions, they stayed in touch.

Baker: The poor Whos, I mean, I never got complaints from them. Mind you, they didn’t have to wear the hairy suit, but they had basically the same padding that Jim had. It’s foam latex, a material that’s been used in film since 1939. The Wizard of Oz used foam latex. It’s basically a sap of a rubber tree with zinc and sulfur added and soap added and yooneu whip air into it. The more air you whip into it, the softer and more flexible it is. And you inject it into a mold, and you have to bake it for eight hours, and that was very difficult because we had 90 Whos. And every day it’s a use once and throw away, so we had to make so many sets of appliances. And after you bake it for eight hours and remove it from the mold, not every one works. I used to figure a one-in-five success rate because you might get a bubble or something. We made literally thousands of appliances for this film, all foam latex.

Ryack: And for some reason it was decided among the financial powers that we couldn’t have all of them with snap crotches. For God’s sake, why couldn’t they all be able to undo their fat suits for the bathroom? That would’ve been a nice thing to do.

Irwin: It was a war of attrition. When an army wins by grinding it out. I remember people saying, “I don’t know if I ever need to see another wrapped present in my life.”

Grazer: Things were still really, really challenging, so I thought I would entertain Jim. I came up with names of people, Hollywood luminaries like Don Knotts or Jerry Lewis, that would come visit him on set.

Irwin: One day, there’s a voice that’s unmistakable, and the whisper goes around: It’s Tony Curtis. He was there saying, “Yeah, we shot Spartacus over here.” Then Eddie Murphy came on, because they were shooting a Dr. Doolittle or Nutty Professor movie or something. He came on in full makeup saying “hi” to people, and we’re all in makeup talking to him.

Eddie Murphy visiting Jim Carrey on the set of How the Grinch Stole Christmas.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Stein: I remember Steven Spielberg coming to the set and sitting in a director’s chair and kind of just looking at me like, Wow, tripping out. And I remember Renée Zellweger being on the set. She was dating Jim Carrey, and I think they dressed her up as a Who once to surprise Jim.

Howard: My dad was also almost like a spirit guide. He was about 70 years old and was working every day on the movie. I created one character for him, but he was so good that we wound up grabbing a line here and a moment there so that he could be in it almost every day. He just quietly showed up on time, sat in that chair for the required three hours, and acted like he was having the time of his life.

And Jeffrey Tambor was just so haphopy to be there every day. My brother Clint tells this story. Clint went, “Don’t you get a little tired of this tone?” And Jeffrey said, “No, in England, this is pantomime. This is what artists dedicate their lives to, this tone and style.” I think he was right. We were making something with a particular tone that stands on its own stylistically and seems to be kind of timeless.

Mary Stein (Miss Rue Who): One thing I remember most is this moment when it was the last shot of the day. And in it, Jim and Jeffrey Tambor, playing the mayor of Whoville, were having this shouting match, and they were getting closer and closer. And Jim Carrey bit Jeffrey’s Who nose off! He brought the house down, and that was the last shot of the day.

Irwin: Working with Molly Shannon was a particular joy, and she’s also mad as a hatter. One of the great blessings was getting to report to work at whatever time it was, 5 a.m. or whatever. Billy Corso and his close associate Kenny Myers were masterful prosthetic makeup artists. It was Kenny’s job to do Molly. And he said, “Honey, you can’t use your phone.” “Oh no, I won’t. I won’t.” Then she came back from a break and Kenny looked over to the rest of us and pointed: There was a cell-phone-shaped indent in her makeup. A flip-phone-shaped indent.

Ryack: Taylor was adorable. She was very into it. She loved her little costumes. In the beginning, she has her little pink coat with a gray fur collar, and this Seuss-y little animal fur backpack we made. The day she had to climb Mount Crumpit, she had her little cape and earmuffs, and she was so excited about that. Another day, she said, “I’m not going to hike today?” And her mother said, “No, not today.” And she cried. I’ll never forget that.

Croughwell: The way films were made prior to the onslaught of CG and now AI – it’s real, it’s something that you can feel. Not only for the performers but for the people that are watching it. It’s a real place. It exists. It’s not some made-up world.

Irwin: If it was two, three years later, we’d have all been looking at tennis balls. It’s gotten better since, but at that time, the actor was the one who ended up with egg on their faces because they didn’t really know where that tennis ball should go. Some AD sets it up, and you do your best, and then you see the movie, and guess what? You’re not actually looking at the monster. You’re looking off to the side and you look like a jerk.

Howard: CGI was expensive and difficult at that point. It hadn’t yet become user-friendly. We tried to stay in-camera as much as possible. In another two or three years, it would’ve been a much different-looking movie. Whether it would’ve held the charm that it seems to hold today, I don’t know. I have no idea. Because I would’ve used the tools.

How the Grinch Stole Christmas would prove to be one of 2000’s biggest box-office hits. It had the highest opening of any Ron Howard or Jim Carrey film up to that point. Critics, however, weren’t exactly impressed. “Shrill, strenuous and entirely without charm,” wrote Todd McCarthy at Variety. “Watching it feels like being gridlocked at Toys ‘R’ Us during the Christmas rush,” wrote Stephen Holden at the New York Times. “I think a lot of children are going to look at this movie with perplexity and distaste,” wrote Roger Ebert at the Chicago Sun-Times. Still, some praised Carrey’s performance. “In a part he seems almost predestined to play, Carrey uses his unequaled physicality and a face so mobile it seems computer-generated to turn the grumpy green monster into an antic combination of Chewbacca and Jerry Lewis,” wrote Kenneth Turan at the Los Angeles Times. In the meantime, an entire generation grew up with the film, and its popularity has only grown. ABC paid $60 million for the TV rights to the film for ten years and then renewed the license. Nowadays, it regularly tops the streaming and pay-per-view charts around the holidays.

Ron Howard’s Whoville.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Grazer: I remember when Audrey Geisel saw it. She sat in the front row of the near-empty Alfred Hitchcock Theater. She was all alone. I was in the back with one other person. She gets up, and she’s elated. She loved it so much. It makes me feel emotional now. We all put so much of ourselves into this that — I did — I cried.

Howard: The reviews were mixed. But they weren’t mixed nice. Either people dug it and got Jim, or else they were harsh. I try not to read reviews, but I always do, to this day. It’s kind of the coward’s way out to not read them. What I do is bundle them up and wait.

Grazer: I have the reviews paraphrased. I don’t read them. I produced 11 or 12 years of straight comedies, and there was a movie, Housesitter with Steve Martin and Goldie Hawn, that was my idea. I wrote the outline, but I don’t think I took a credit. It was like a triple and got good reviews, but mixed. I read this one really bad review, where the reviewer didn’t like the story and said, “It’s obviously the story of the producer” or something like that. I was singled out! That night, I woke up, and my lip had literally exploded with a cold sore. I was so nervous. I started this habit of leaving the country so I didn’t have to read reviews. I went to the Osa Peninsula in Costa Rica, because you’re off the grid. I would just do that — leave.

Howard: The combination of that brilliant Chuck Jones cartoon and the book was steep competition, and it would be hard to convert people immediately and impress them. But I was disappointed because there was no denying that Jim was dazzling. I thought he should have been nominated for an Oscar that year. Honest to God. I’d been around some strong performances already in my career, and I felt this was noteworthy. The two most difficult performances that I’ve been a party to were Russell Crowe in A Beautiful Mind and Jim Carrey in The Grinch. To me, they’re both real feats of artistry for very different reasons.

Momsen: I definitely don’t remember the critics. I don’t think I knew critics existed at that age. I remember the kids in my school being critics. I moved around a lot, and being a child actress going from school to school always made for a weird schooling environment. People were not always the nicest. I was fully “Grinch girl” by the time the film came out.

Baker: We had a royal premiere in England, and we met the Queen. But they don’t know the Grinch there. They didn’t know what to make of the movie. It was a weird response. Because the book is an American classic. And it’s a Christmas movie, which is smart, because every time the holiday comes around, you play it.

Howard: The film was incredibly commercial. One stunt coordinator that I know calls it “the green salve.” When a stunt person gets hurt on a job, but then they go around and get a check, you say, “Well, he’s feeling a lot better with that green salve.” We experienced that with The Grinch. It’s been gratifying to see it sustain and gain this place in people’s holiday patterns.

Momsen: I formed my band the Pretty Reckless when I was 14, and every year The Grinch comes up as Christmas comes around and fans put the two worlds together and realize that this singer was this little girl and this little girl is now this singer. Every year they would ask me to do a rock version of “Where Are You Christmas.” And for 15 years I said, “No way. That’s never going to happen. In zero worlds is that something I would do.” And every year the comments grew exponentially.

Fast-forward to 2020, life has become hard for everyone. Personally, I had gone through a lot of loss. The band was in a very dark space. COVID was not helping matters. And there was nothing to do because we were on lockdown. And I go, “People really want this version of the song. Is this something that we should try?” So we put together a little arrangement, which is strangely tricky because the song itself is only a minute and a half. We go into rehearsal, we play through it once, and by the end of the song these four miserable Grinches, we couldn’t help it, we were smiling, laughing, having a great time for the first time in a long time. So that was the kicking-off point. A couple of years later, we ended up in the studio starting to record it. I wasn’t expecting that, dueting with my 5-year-old self. It sounds cute, but actually doing it, I teared up.

I just saw Jim at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame for the first time in 25 years, because he was inducting Soundgarden and I was performing with Soundgarden. The universe aligned in the most insane way ever. It was like seeing family.

Carrey: When I heard that Taylor was going to be singing with them, I couldn’t believe it. I turned around in the hallway, and she was standing there. I don’t know if she had heels or not, but she’s towering. I’m going, “What?” She has a really powerful manner. I was so glad she’s done so well for herself. She’s been through some challenges in her life and come out the other side. It was very exciting to see her again. And she brought me a Crunchie, which is my favorite chocolate bar. That was awesome.

Irwin: I did not foresee it becoming this kind of classic. I remember thinking this was going to be an interesting kind of almost anti-Christmas movie. But people now sometimes say to me, with teary eyes, “We watch it every Christmas, and we all snuggle up with cookies and popcorn.” And I’m thinking, “Well, that’s what we used to do with The Wizard of Oz.” It’s a testament to Ron and Jim’s mastery. They made something that is weird and wild and of the year 2000 but also still timeless. And yeah, critics didn’t like it, but it’s a movie that seems to sit with people.

Howard: I was so exhausted by The Grinch that even when I was in the small group of people who were being reached out to for exploratory conversations about Harry Potter, I was just so out of gas on that tone that I didn’t even engage. But, you know, we’ve fleetingly toyed with the notion of another Grinch. I have a take that Jim gets a kick out of, and the guys would come back and write it. None of us are sure we want to really go there again. But the one thing is I’ve been able to say to Jim, “You might have to wear the suit, but you wouldn’t have to wear the makeup, and certainly not the contact lenses.” We would still have exactly the same look because we have so much film to work with of him in the makeup that we could solve that digitally.

Carrey: Now, you see it as part of the culture. It’s funny to see it now in Walmart commercials and things like that. Though it was a struggle, it’s such an honor to have been that character. It’s just the most beautiful story in the world, how badly we need people to open their hearts. It’s always going to get you. Many of us are walking around with a desiccated heart right now.

Related

Produced by George Lucas and directed by Howard, this big-budget, special effects-filled 1988 fantasy extravaganza starred Warwick Davis, Val Kilmer, and Joanne Whalley. While it didn’t achieve the monumental success of Lucas’s Star Wars, its fanbase has grown over the years.

The original credited writers did not respond to a request for comment.

The films they worked on included See Spot Run, Shark Tale, Men in Black 3, Monster House, an earlier version of Curious George, and at least one Dr. Dolittle movie.

According to Mandel, Apatow was working as a kind of advisor to Carrey at the time.

Anthony Hopkins is the narrator, who delivers new lines like, “Inside a snowflake, like the one on your sleeve, there happened a story you must see to believe.”

“For example,” Mandel explains, “we came in at the end of Borat, and the three of us are actually the ones that pitched the new ending of Borat, but we never arbitrated. So, if you watch the end credits of that movie, we are given a special thanks. It doesn’t say why, but they were allowed to thank us for the work we did because we never arbitrated.”

In Milos Forman’s 1999 biopic Man on the Moon, Carrey portrayed the late comic Andy Kaufman, and reportedly disappeared into both that role and that of Kaufman’s comic alter ego, Tony Clifton.

Released this past November by her band the Pretty Reckless, “Taylor Momsen’s Pretty Reckless Christmas” is a six-track EP that includes a new cover of the song “Where Are You Christmas,” which she sang as a child in How the Grinch Stole Christmas.

“He also wore a wood stove, and we did have a wood stove made with a little CGI fire inside,” Ryack adds. “His Santa suit was very important, too. Everything was very method-y for me. I thought, well, what would the Grinch have in his lair? It’s made out of terry cloth. Maybe he had some old red towels there. We washed the fabric to death, so it looks like an old towel.”

Howard’s mother, Jean Speegle Howard, had been an actor in her youth and appeared in some of her son’s movies as well. She died September 2, 2000, and How the Grinch Stole Christmas is dedicated to her. “My mom was sick,” during shoots, Howard explains. “We were filming on the Universal lot, and she was at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Burbank, so I could get to her. And my dad and brother, who both had roles in the movie, were popping over to visit as well. I dedicated the movie to her because she just loved Christmas. My mom passed away several months before the movie came out.”

Ron Howard’s younger brother Clint, also an actor, often appears in the director’s films. He plays mayoral aide Whobris in How the Grinch Stole Christmas.

Telling the story of a young boy’s friendship with a large bear, Gentle Ben ran on CBS from 1967 to 1968. Clint Howard, around eight at the time, played the lead role. His father, Rance, was also a series regular and wrote some episodes.

Mary Stein, who plays Miss Rue Who, confirmed that the Who actors stay in touch, though we were unable to track down actual marriage certificates.

As he often did in his films, Howard cast his father, veteran actor Rance Howard, this time as The Elderly Timekeeper.

When the first Harry Potter movie was in development, directors who were considered included Steven Spielberg, Terry Gilliam, and Rob Reiner. Chris Columbus eventually directed the film, which went on to gross $1 billion.