India’s Chandrayaan‑3 mission has revealed that the Moon’s south pole is much more electrically active than scientists expected. This region, once thought to be quiet and calm, actually has a lively and energetic electrical environment.

From August 23 to September 3, 2023, the Vikram lander gently recorded tiny charged particles moving around it. Using its ultra‑sensitive RAMBHA‑LP instrument, it discovered that the Moon’s south pole isn’t silent at all; it’s buzzing with electrical activity.

And for the first time, humanity has measurements taken right at the surface, not inferred from afar.

Plasma, the so‑called fourth state of matter, is usually associated with stars, lightning, or fusion reactors. But the Moon, despite its airless silence, also hosts a delicate veil of plasma. It forms when solar wind slams into the surface, sunlight knocks electrons loose through the photoelectric effect, and Earth’s magnetotail occasionally sweeps over the Moon, bathing it in charged particles.

Moon’s magnetic mystery solved? Why are some rocks on the moon highly magnetic?

This tenuous mix of electrons and ions forms the lunar ionosphere, a region so thin that earlier missions could only study it indirectly. Chandrayaan‑3 changed that.

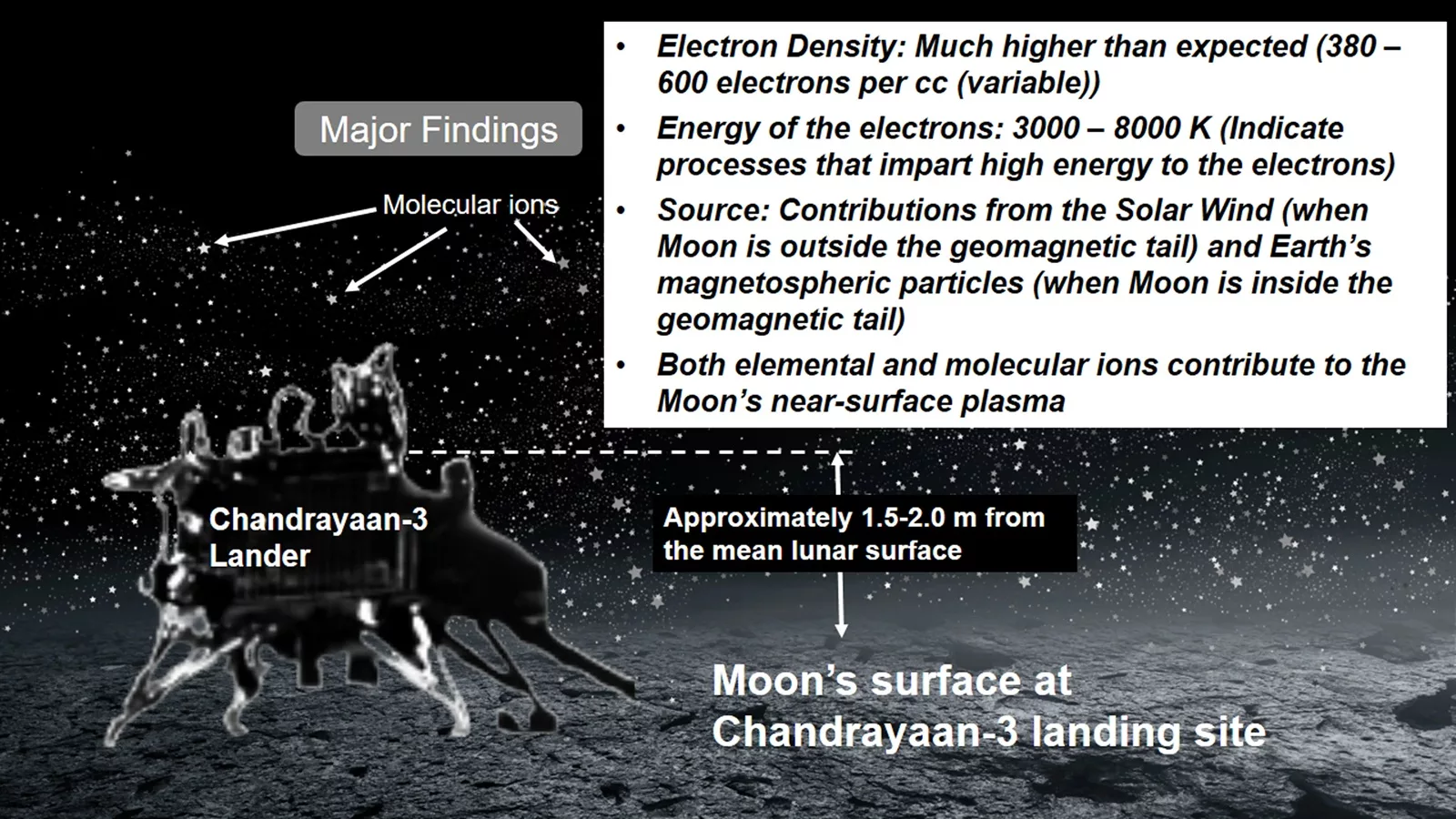

At Shiv Shakti Point (69.3° S, 32.3° E), RAMBHA‑LP measured electron densities between 380 and 600 electrons per cubic centimeter, numbers that startled researchers.

These values are significantly higher than estimates derived from radio‑occultation techniques used by orbiters, which observe how radio waves bend as they skim the lunar atmosphere.

For the first time, scientists now have ground truth: the plasma hugs the surface more tightly and more energetically than models predicted.

Lunar soil can potentially generate oxygen and fuel

Even more striking was the energy of these electrons. Their kinetic temperatures ranged from 3,000 to 8,000 Kelvin, hotter than molten metal, despite the frigid lunar night just centimeters away.

This suggests that the Moon’s surface is not merely a passive dust‑covered rock but a stage where sunlight, solar wind, and magnetic forces continuously sculpt an invisible electrical landscape.

The study reveals that the lunar plasma is not static. It shifts dramatically depending on where the Moon is in its orbit:

During Lunar Daytime (Outside Earth’s Magnetosphere):

The plasma is shaped by the solar wind interacting with the Moon’s sparse exosphere. During Passage Through Earth’s Magnetotail: The plasma is dominated by charged particles streaming from Earth’s elongated magnetic tail, a region that the Moon enters for 3–5 days each month.

This dual influence creates a constantly evolving electrical environment, one that future lunar explorers will need to understand intimately.

Using an in‑house Lunar Ionospheric Model (LIM), scientists found that not just elemental ions but molecular ions, possibly from trace gases like CO₂ and H₂O, contribute to the plasma layer.

This hints at subtle chemical processes occurring near the surface, adding another layer of complexity to the Moon’s “airless” environment.

The findings from RAMBHA‑LP are more than scientific curiosities. They are essential for designing future landers and habitats that must withstand fluctuating electrical conditions, understanding how dust behaves in charged environments, planning long‑term human presence at the lunar south pole, and refining communication and navigation systems for surface missions.

Indian Scientists develops a way to build bricks on the moon

As nations and private companies set their sights on the Moon’s south pole, home to permanently shadowed craters and potential water ice, Chandrayaan‑3 has delivered a crucial piece of the puzzle.

In just 10 days of operation, Vikram’s instruments have rewritten what we thought we knew about the Moon’s electrical personality. The South Pole, once imagined as a cold, inert wilderness, now appears to be a place where invisible forces crackle and shift with cosmic rhythms.

Chandrayaan‑3 may have gone silent, but the data it sent back continues to speak, revealing a Moon that is far more electrically alive than anyone expected.

Journal Reference:

G. Manju et.al. In situ ionospheric observations near the lunar south pole by the Langmuir Probe on Chandrayaan-3 lander. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. DOI: 10.1093/mnras/staf1276