The magnificent island of Bermuda. Credit: Wallpapercat.

The magnificent island of Bermuda. Credit: Wallpapercat.

Far out in the Atlantic, Bermuda rises from the ocean as if it’s breaking the rules of geology. It sits on a broad hump in the seafloor, about 500 meters above the surrounding seafloor, yet its volcanoes shut down more than 30 million years ago.

Typically, once a tectonic plate drifts away from a deep mantle hotspot, the cooling crust and volcano slowly sink. Is this yet another Twilight Zone mystery owed to the famous Bermuda Triangle?

Not so fast. Now, scientists say they know why Bermuda never sank. Deep beneath the island lies a massive slab of ancient magma, frozen in place and quietly propping the island up.

This conclusion comes from a detailed seismic study published in Geophysical Research Letters, led by seismologist William Frazer of Carnegie Science and Jeffrey Park of Yale University.

Instead of a plume of hot rock rising from Earth’s depths, Bermuda appears to be floating on the geological equivalent of a submerged life raft.

Listening For the Planet’s Echoes

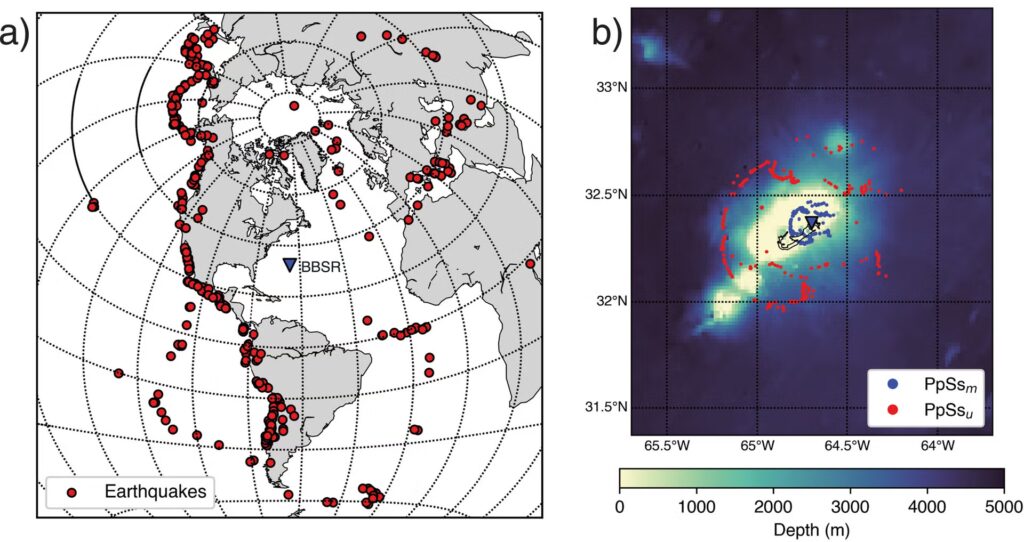

(a) Map of earthquakes used in this study. (b) Piercing points for PpSs phases for the interpreted Moho and underplated layer for seismic events in (a) for the velocity model. Credit: Geophysical Research Letters, 2025.

(a) Map of earthquakes used in this study. (b) Piercing points for PpSs phases for the interpreted Moho and underplated layer for seismic events in (a) for the velocity model. Credit: Geophysical Research Letters, 2025.

Most volcanic islands, like Hawaii, form above mantle plumes. Hot material rises, melts, and punches through Earth’s crust, creating volcanoes and lifting the seafloor in the process.

As tectonic plates move, those islands drift away from the plume. They cool, slowly sink into the seafloor under the enormous weight, and only leave a trail of aging volcanoes behind. Over millions of years, many of those once-towering volcanic islands subside below sea level. They become underwater volcanoes called seamounts, or, if erosion flattens their tops near sea level, guyots.

A classic example is the Hawaiian–Emperor chain. Hawaii’s Big Island is active and above water. Farther northwest, the islands are older, lower, and eventually disappear beneath the ocean.

Bermuda doesn’t fit that script, though. It has no chain of progressively older islands, no sign of ongoing heat, and no clear plume beneath it.

To investigate, Frazer and Park turned to seismic waves from distant earthquakes. A single borehole station on Bermuda has recorded global quakes for decades.

The team analyzed signals from 396 earthquakes, each strong enough to send clean vibrations through Earth. As those waves passed through different layers underground, they changed speed and direction in ways predictable only by the presence of certain materials. Those changes left behind faint echoes, like sonar pings. By stacking and filtering them, the researchers built a vertical picture of the rocks beneath Bermuda.

What they found was startling.

Below the island’s volcanic rocks and normal oceanic crust sat a thick, unexpected layer. It began about 21 kilometers down and stretched for another 20 kilometers.

That level of thickness has never been seen in any other similar layer worldwide.

“Typically, you have the bottom of the oceanic crust and then it would be expected to be the mantle,” Frazer told Live Science.

“But in Bermuda, there is this other layer that is emplaced beneath the crust, within the tectonic plate that Bermuda sits on.”

A Long-Lasting Geological Life Raft

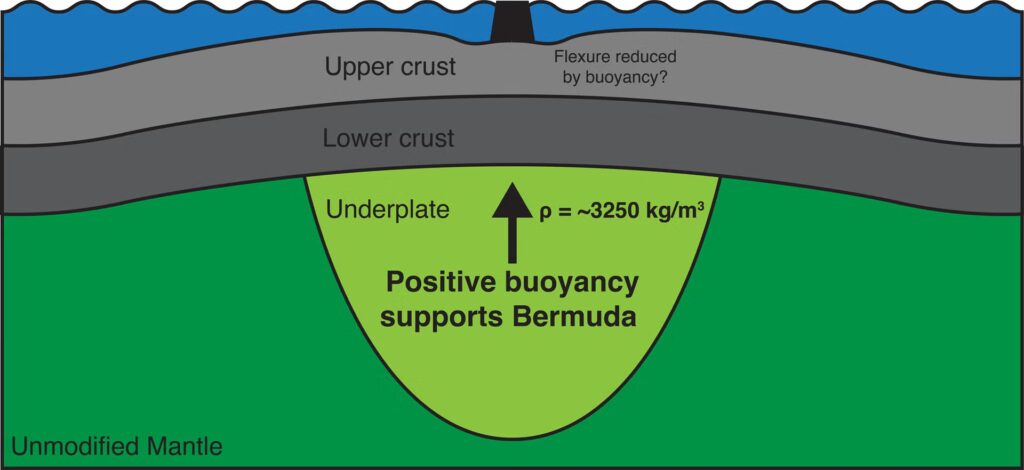

Schematic of newly refined Bermuda geology. Credit: Geophysical Research Letters, 2025.

Schematic of newly refined Bermuda geology. Credit: Geophysical Research Letters, 2025.

The researchers interpret this deep layer as underplating. That happens when magma rises but stalls beneath the crust instead of erupting. Over time, it cools into a broad, solid sheet of rock. Under Bermuda, that sheet is unusually thick and slightly lighter than the surrounding mantle.

That small difference matters. The team calculated that if this layer is just about 1.5% less dense than normal mantle rock, it could lift the seafloor by roughly 500 meters.

That’s almost exactly the height of the Bermuda swell.

The idea fits other clues. Bermuda shows positive topography but negative gravity anomalies, a sign of low-density material below. Heat flow around the island looks normal, not elevated. That’s hard to square with a hot plume, but easy to explain with cold, buoyant rock.

“There is still this material that is left over from the days of active volcanism under Bermuda that is helping to potentially hold it up as this area of high relief in the Atlantic Ocean,” geologist Sarah Mazza of Smith College told Live Science.

A Unique Window into Geology

Mazza’s own work adds another layer to the story. Bermuda’s lavas are rich in carbon and low in silica, pointing to recycled material from deep within Earth. That material likely dates back to the formation and breakup of the supercontinent Pangea.

When the Atlantic Ocean opened, it may have inherited a strange patch of mantle unlike anything beneath older oceans.

“The fact that we are in an area that was previously the heart of the last supercontinent is, I think, part of the story of why this is unique,” Mazza said.

The new study suggests that this volatile-rich history helped create a thick underplated layer. Magma may have pooled beneath the crust, while rising melts altered the mantle, leaving behind lighter rock.

When asked how such a massive layer could form, Jeffrey Park told Brighter Side of News that “some magma may have stalled beneath the Moho instead of erupting, building a mafic pluton over time.”

“We found volatile rich melts rising beneath Bermuda could also have efficiently depleted and modified the uppermost mantle, leaving behind a lighter residue,” he added.

Frazer now plans to look beneath other islands. He wants to know whether Bermuda is a rare exception or simply the clearest example of a process scientists have overlooked.

“Understanding a place like Bermuda, which is an extreme location, is important to understand places that are less extreme,” Frazer said.

“It gives us a sense of what are the more normal processes that happen on Earth and what are the more extreme processes that happen.”