For about 540 million years, Earth’s magnetic field and the oxygen in its air have risen and fallen together. A NASA-led team has now measured that link, suggesting the planet’s molten core helped create the long-term conditions necessary for complex life to evolve.

The work was led by Weijia Kuang, a geophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Maryland. His research focuses on how Earth’s deep interior and magnetic field influence the planet’s habitability.

Earth’s geomagnetic field, which is the invisible magnetic bubble created by motion in the planet’s liquid core, stretches far into space and steers charged particles.

Changes in that field happen because molten iron in the outer core flows in complex patterns rather than in a steady, uniform way.

In this new study, the team compared a long record of magnetic field strength to matching estimates of atmospheric oxygen.

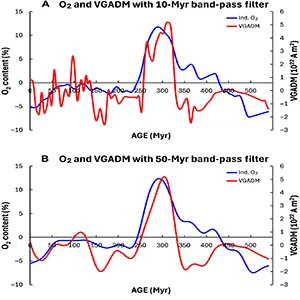

They found that both curves climb overall, and share a peak between about 330 and 220 million years ago. When those histories are plotted together, the lines nearly trace each other exactly.

Earth’s core and magnetic field

Streams of charged particles called the solar wind, a steady outflow from the Sun, constantly crash into Earth’s magnetic bubble.

Deflecting much of that space weather helps protect our atmosphere and surface from some of the harshest radiation.

Spacecraft data from Earth, Mars, and Venus show that a magnetic field can reduce atmospheric loss while also opening escape routes near the poles.

One analysis reported that, under some conditions, planets with and without internal fields can lose similar amounts of gas.

Because of that nuance, the new work does not simply claim that a stronger magnetic field always locks in more oxygen.

Instead, the authors argue that a slow shared process inside Earth likely drives magnetic activity and the balance of oxygen at the surface.

Strong link between Earth’s oxygen level and geomagnetic dipole revealed since the last 540 million years. (A) 10-Myr band-pass filter (their correlations are shown in Fig. 2). (B) 50-myr band-pass filter. (C) 120-Myr band-pass filter. Both VGADM and O2 peaked in the 120-Myr time interval between 230 and 350 Myr. However, O2 peaked later than VGADM, but the time lag decreases as the band-pass filter period increases, until no lag at all after applying the 120-Myr band-pass filter. Credit: Science Advances. Click image to enlarge.Rocks hold magnetic field records

Strong link between Earth’s oxygen level and geomagnetic dipole revealed since the last 540 million years. (A) 10-Myr band-pass filter (their correlations are shown in Fig. 2). (B) 50-myr band-pass filter. (C) 120-Myr band-pass filter. Both VGADM and O2 peaked in the 120-Myr time interval between 230 and 350 Myr. However, O2 peaked later than VGADM, but the time lag decreases as the band-pass filter period increases, until no lag at all after applying the 120-Myr band-pass filter. Credit: Science Advances. Click image to enlarge.Rocks hold magnetic field records

As lava cools on the seafloor, mineral grains line up with the field and form a paleomagnetic record, a frozen record of field direction. If those rocks stay cool enough, they preserve that signal for hundreds of millions of years.

Scientists infer past oxygen levels from geochemical proxies, which are chemical clues in ancient rocks that respond to how oxygen was distributed in air and seawater.

These clues include the chemistry of iron, sulfur, and carbon, plus signs of wildfires that only burn when oxygen is above certain thresholds.

Work combining rock data and modeling shows that, after complex animals appeared, atmospheric oxygen mostly lay between about 15 and 30 percent.

One review highlights a late Paleozoic pulse when oxygen may have climbed close to 35 percent before dropping again.

Geochemical work on molybdenum in ancient seabed rocks links major ocean oxygenation steps to the spread of land plants and large predatory fish.

That pattern supports a broader connection between oxygen rich environments and bursts of complex life.

Earth’s core and supercontinents

Over millions of years, continents assemble into clusters and break apart again in a supercontinent cycle, which is simply a repeating pattern in plate tectonics.

Those reorganizations rearrange ocean basins, mountain belts, and the way heat moves out of Earth’s mantle and core.

Studies of past supercontinents, such as Pangea, suggest that these cycles can reshape long term climate and ocean circulation.

The work argues that supercontinent assembly and breakup may influence atmospheric gases by changing volcanism and weathering rates.

Kuang and colleagues suggest that such deep Earth processes may explain why field strength and oxygen track each other over the span they examined.

Continental motions could modulate heat flow at the core-mantle boundary, which affects the dynamo, and change gases released or removed at Earth’s surface.

The study’s authors emphasize that the match between the two records does not prove a simple cause and effect chain.

Earth’s core, oxygen, and life

Earth is the only known planet with both complex oxygen breathing life and a strong global magnetic field.

That coincidence has tempted scientists to treat the field as part of planetary habitability, the ability of a world to support life.

The new correlation does not settle how a magnetic field shields air, yet it strengthens the idea that a planet’s interior matters.

For rocky exoplanets, astronomers may need to think about both distance from the star and how active their cores and plates are.

Future work will test whether similar links appear earlier in Earth’s history or in other chemical cycles such as nitrogen.

For now, the results show that deep core processes have moved in step with the air we breathe.

Untangling that partnership could help explain why life on Earth endured so many upheavals and guide the search for other long lived worlds.

The study is published in Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–