When a brilliant artist of any discipline reaches their twilight years — which in popular music is one’s mid-to-late thirties — the best you can usually hope for is good rather than great.

That initial lightning bolt of inspiration is in the rear-view mirror, and although there’s an occasional spark that reminds you of who they were and sometimes still are, the artist is in a constant battle with their former selves. They might still crush it live, but there’s a reason why the new songs are bathroom breaks. Some accept it; others try, with seeming desperation, to stay relevant or, worse, edgy. Most of them probably sometimes feel like the Pretenders’ Chrissie Hynde did a few years ago when asked for one autograph too many — “Haven’t I done enough?!”

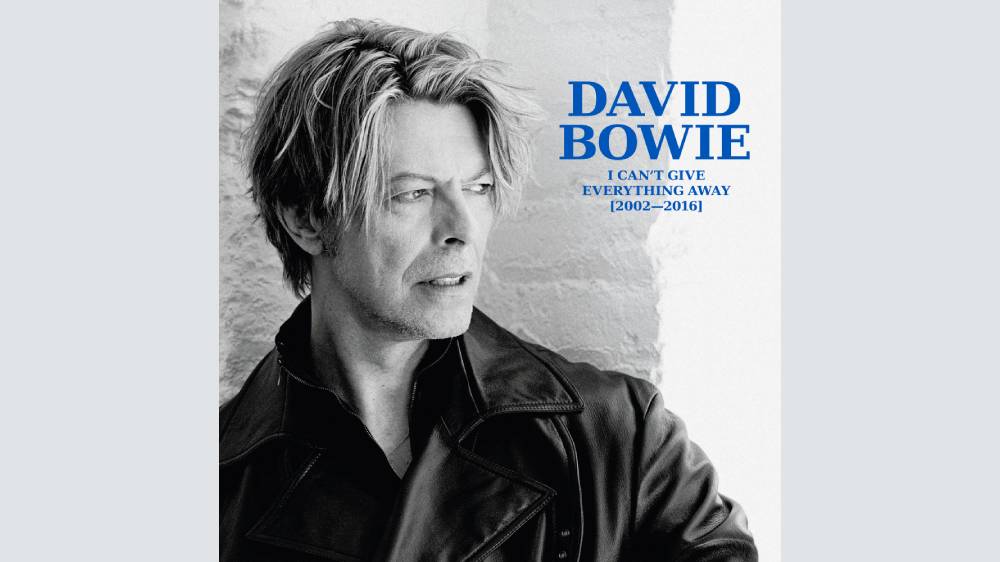

Sure, there are rare exceptions: Miles Davis, Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell and Neil Young all had late hot streaks. But the greatest must be David Bowie, whose final album, “Blackstar” — written and recorded as he underwent treatment for cancer, and released two days before his death — was his most innovative and exciting work in 35 years.

“Blackstar” is the final chapter in “I Can’t Give Everything Away,” the sixth and chronologically final installment in the series of career-spanning boxed sets overseen by the man himself in the years before his death. At the core of the set are four studio albums — “Heathen,” “Reality,” “The Next Day” and “Blackstar” — recorded at opposite ends of the years between 2001 and 2015 (along with two sprawling live albums and three full CDs of stray songs). The reason, or at least the impetus, for the decade-long hiatus in the middle came when Bowie suffered a heart attack onstage in 2004 toward the end of the exhausting, 112-date “Reality” tour and apparently decided he’d had enough.

The first three of those albums are basically a continuation of the creative revival that began with the “Outside” album in 1995. After Bowie’s albums had reached a nadir in the early ‘90s with the hard rock of “Tin Machine” and an attempted return to “Let’s Dance”-style pop with “Black Tie White Noise,” he apparently re-engaged with his muse; not coincidentally, also during this time he got sober, got married and settled in New York. He remained competitive and intensely aware of contemporary alternative music (much of which bore his influence), and consequently, some of those ‘90s albums tried far too hard to fit in with the trends du jour, particularly industrial rock and drum n’ bass.

But by the time of “Heathen,” he wasn’t following any trends, and the album was an unusual combination of driving rock, experimental tracks so low-key they bordered on maudlin, and incongruously sprightly moments like “A Better Future.” Significantly, the album also reunited him with producer Tony Visconti, with whom he’d worked off and on since the mid 1960s, and who would work on everything he recorded after. While uneven, it’s a challenging and moody work.

During this era, Bowie cast a wide net — “Heathen” features guest appearances from Pete Townshend and Dave Grohl, and at other points Moby, Air, LCD Soundsystem’s James Murphy and others contributed remixes (the latter was invited to co-produce “Blackstar” but backed out after a couple of sessions, saying he was “overwhelmed”). But he also sprinkled in winking references to his own discography, from the “Absolute Beginners”-evoking “Ba-ba-ba-ooo” backing vocals on “Everybody Says Hi” to the Berlin references in “Where Are We Now?” and even a blast of “Crack City” in “Never Get Old.”

The following “Reality,” recorded just a year after “Heathen,” was a much livelier affair that its predecessor, intended to showcase Bowie’s powerhouse live band. There are many more rock songs — with deliciously distorted guitars and powerhouse drumming — and some are among the best of this period, notably “New Killer Star,” “Days” and the title track.

The following tour — Bowie’s last — is collected on the massive “Reality Tour” set, with a whopping 33-song setlist that embodies the above-mentioned challenges of being a later-in-life rock legend: One sequence finds him moving from the mid-‘70s deep cut “Breaking Glass” to the new “Never Get Old,” followed by “Changes.” Although overstuffed, it’s the definitive career-spanning live Bowie album, and includes a stellar version of “Heroes” that starts off with a rough, guitar-driven arrangement that gradually morphs into the familiar one; by the time of the song’s anthemic coda, it’s hard not to feel a lump in the throat, no matter how many times you’ve heard it in the past.

Curiously, although some ten years elapsed between “Reality” and the following studio album “The Next Day,” it’s largely a continuation, with many of the same musicians and a similar combination of unexpectedly driving rock and experimental tracks.

Yet none of the above hinted at what was coming next. Bowie recorded “Blackstar” while staring his mortality in the face, and the intensity is palpable in every note of the album. Working with jazz saxophonist Donny McCaslin and his ace band, the music is completely different from anything Bowie had done before, often just as driving as the preceding rock albums but much darker — particularly the eerie title track, which combines a haunting opening with a glorious middle section that is like the sun parting clouds, until the lyrics come in: “Something happened on the day he died/ Spirit rose a meter and stepped aside/ Somebody else took his place, and bravely cried/ ‘I’m a blackstar, I’m a blackstar.’” Images of death and the afterlife are in nearly every song — one begins, “Here I am up in heaven” — but the album closes on an upbeat note with “I Can’t Give Everything Away,” which features a distant harmonica and “Heroes”-esque guitar tone (recalling his mid-‘70s “Berlin” era) and a characteristically contradictory parting line: “Seeing more and feeling less/ Saying no but meaning yes/ This is all I ever meant/ That’s the message that I sent.”

It concludes what may be the most remarkable final act of any entertainer’s career: The album was released on January 8th, 2016, his 69th birthday — two days before his death. Of course he couldn’t have planned it so specifically, but it’s hard to think of an artist who played themselves off so memorably. It’s an extraordinary final statement.

This era served up so many stray tracks that the “Recode” odds-and-ends compilation that accompanies all of the boxed sets in this series sprawls across three full CDs. Many of them are for completists only (did we really need SACD mixes, if anyone remembers what those are?) but along with the companion EPs that followed his final two albums, highlights include James Murphy’s “Steve Reich mix” of “Love Is Lost” (which incorporates winking elements from “Ashes to Ashes”); the Metro remix of “Everyone Says Hi,” with its breezy electronic feel reminiscent of Tame Impala; a wild remix of “Disco King” featuring Tool’s Maynard James Keenan and Chili Peppers guitarist John Frusciante; an oddball collaboration with Lou Reed called “Hop Frog”; and a completely bonkers version of Sigue Sigue Sputnik’s snarky 1986 song “Love Missile F1-11,” one of several unexpected covers from this era including Jonathan Richman’s “Pablo Picasso,” the Pixies’ “Cactus,” the Kinks’ “Waterloo Sunset,” and “Try Some, Buy Some,” a song George Harrison wrote and produced for Ronnie Spector in 1971 (if nothing else, they show the range of Bowie’s musical tastes).

The set also includes several of his last live performances: three tracks from the Fashion Rocks show in 2005, including two with Arcade Fire (their “Wake Up” and his “Five Years”), and most interesting of all, a cover of the early Pink Floyd classic “Arnold Layne” with that band’s David Gilmour — a parting tribute to Syd Barrett, the song’s writer and original singer, who cast a vast influence on the young Bowie. (His actual last live performance took place in 2006, a version of “Changes” with Alicia Keys at a New York charity event.)

Bowie’s final chapter found him coming to terms with his own past — there might not have been any more hit singles, let alone another “Heroes,” “Changes,” “Ziggy Stardust” or “Station to Station,” but he’d found a solid cruising altitude that still gave him room to challenge himself, even as he focused on his family and curating his vast archive in the final decade of his life. The results of that curation have continued to roll out with generous frequency in the years since his death, in the form of multiple live albums, the “Moonage Daydream” film, and, not least, the opening of the David Bowie Centre at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum earlier this week, which is currently displaying a fraction of the 90,000 items the museum acquired from his archive.

Bowie guarded that archive zealously during his life, often snapping up items that had wandered off when they popped up on eBay or in auctions, and he kept a majority of it out of circulation, presumably in anticipation of what’s happening now: a tasteful and continuous flow of unreleased or recontextualized material that keeps his work in front of the public, and fans eagerly anticipating what’s coming next. In other words, an artfully curated creative afterlife.