Mimosa Echard

Beatrice Loayza

A material girl in a material world: hyperfeminine stylings commingle with industrial structures and materials in the artist’s exhibition.

Mimosa Echard: Facial, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Amant. Photo: New Document.

Mimosa Echard: Facial, Amant, 315 Maujer Street, Brooklyn,

through February 15, 2026

• • •

In his sprawling, unfinished tome about proto–shopping malls in nineteenth-century Paris, The Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin saw the ambulatory figure of the flâneur as a vision of the future: a perspective in perpetual flux; a psyche cut with shard-like images of the surrounding city, its industrial logic of glass, iron, and steel and its glittering cacophony of commodities. Arguably, in our present world of endless screens, we are all flâneurs, drifting through a phantasmagoria of consumer culture—of “dream images that rise into the waking world.”

Mimosa Echard: Facial, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Amant. Photo: New Document.

A self-proclaimed flâneuse herself, the Paris-based artist Mimosa Echard has fashioned Facial—her first solo show in the US—after fragmented urban experience. From a distance, Facial, which is currently on view at Amant, might resemble a series of sculptural paintings and photographs. But its parts comprise a single installation meant to evoke a hallucinatory trip around New York City, which Echard called a kind of “sexy jail” in an interview with Cultured. The aesthetic treatment brought to mind by the title underscores the show’s investment in facades; in the work of creating impressions in a figurative sense. The word’s usage in porn—in which a performer’s face is a canvas for cum—also hints at Echard’s enchantment with trashier expressions of femininity: the overly contoured, bimbo-ey sort that exists in male fantasy as opposed to real life. Stepping into the gallery space, you’ll immediately spot two overlapping 4×6 photo prints taped to the wall, the image on the bottom covering half of the one above. What we see is a mascara-enhanced eye—the airbrushed, tastelessly aspirational kind used for beauty-salon storefronts—peeking over a set of brick steps covered in leaves and illuminated with tawdry flash.

Mimosa Echard, photograph taken on Grand Street, Brooklyn, 2025. Courtesy the artist.

Other similarly eerie manifestations of this glam single-eyed gaze are scattered throughout the rooms like yassified minions of panopticonic power. They stare at us, alluring and menacing, from isolated photographs or as individual elements in richly layered collages, thick accretions of conventional and found materials with an occlusive veneer. As encapsulated by this sultry surveyor, girlish stylings—earrings, wrapping paper covered in red hearts, leopard print—mesh with the installation’s authoritarian streak. Evocative of the city’s grid system and riffing off what Edith Wharton called “rectangular New York[’s] . . . deadly uniformity of mean ugliness,” the exhibition abounds in latticed patterns and rectilinear formations: a powder-coated drain grate, a short video clip of ant-like cars filtering on and off the Brooklyn Bridge. One photograph shows the topless torsos of several mannequins, their heads obscured by a half-closed rolling shutter. Appearances to the contrary, it’s not really a commentary on the tyranny of female beauty standards—the show is ultimately too wry to feel seriously under the thumb of such pressures; its insights, instead, operate through affective registers; we glean moods and feelings from the material world in the mode of the flâneur’s transient passages.

Mimosa Echard: Facial, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Amant. Photo: New Document.

In 2022, Echard won the Marcel Duchamp prize for her multimedia installation made that year, Escape more, in which liquid flows over a glass wall through which one can make out the blurry pink outlines of what might be a bedroom or studio. This play with transparency and deceptive surfaces is fundamental to Echard’s practice; the artist regularly employs thick layers of disparate substances to create a porous boundary between organic and synthetic objects, masculine- and feminine-coded imagery. Several Plexiglas works in Facial that appear like marbled expanses of bubblegum-pink and gold take on an epidermal density up close. Swirls of dried depilatory wax commingle with oxidized blotches, while crinkly wrapping paper or a bumpy layer of brick wallpaper stickers make up the background. As on the streets of Gotham, urine is splashed throughout, though it’s uncertain where exactly these golden showers have fallen. This riot of textures resembles bacterial cultures suspended in the gooey membrane of a petri dish.

Mimosa Echard, untitled, 2025. Courtesy the artist and Amant.

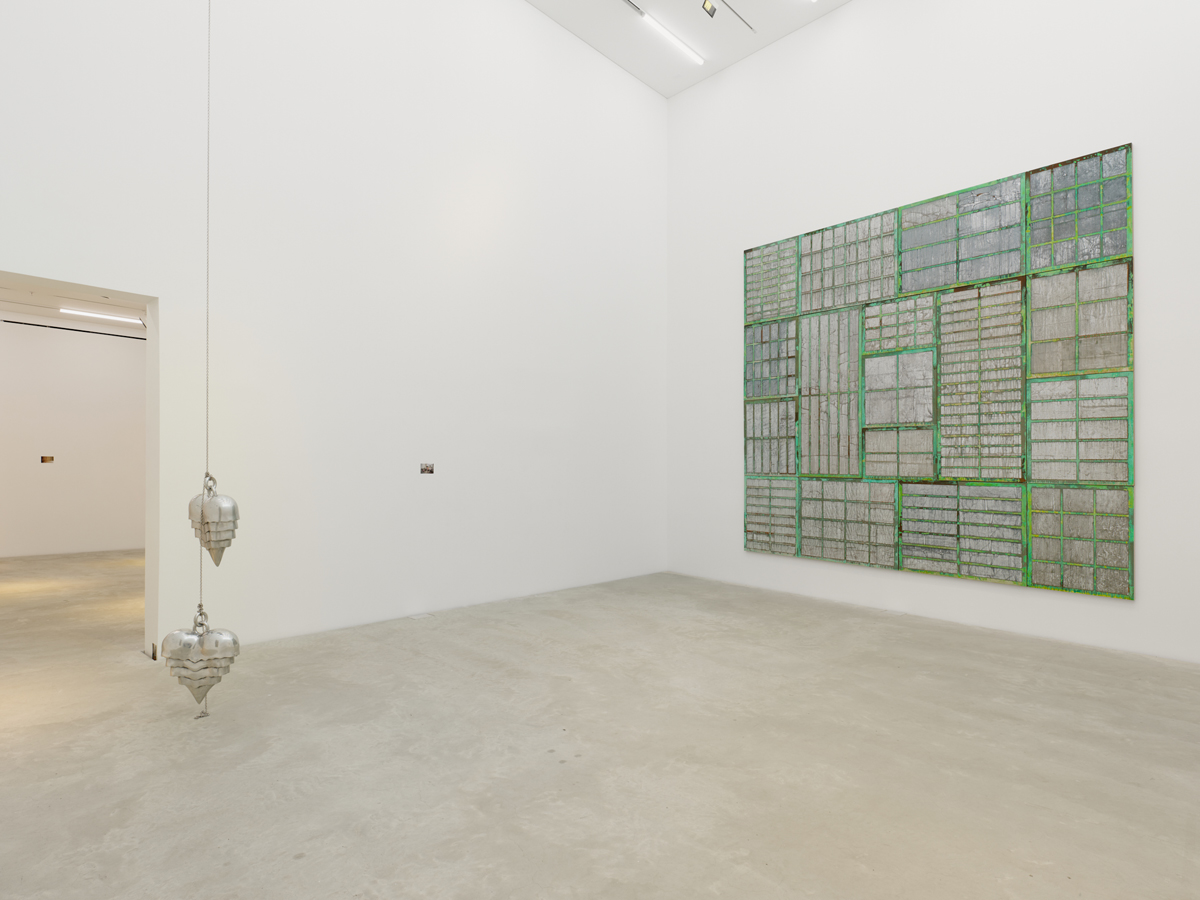

Raised in a hippie commune in the south of France—a community she documented in her 2016 film The People through a psychedelic mishmash of MiniDV camera footage—Echard draws inspiration from plants and the seemingly alien reproductive systems found in nature. Hearkening back to this fascination, the starting point for Facial is the gingko tree, a ubiquitous sight in the city that’s revealed to have strange, ghostly resonances with what Echard views as Gotham’s penal architecture. In Echard’s hands, the noble ginkgo, which has weathered not only Hiroshima but multiple ice ages, recalls, for instance, the stark, windowless monolith at 33 Thomas Street—the only building in New York designed to withstand a nuclear bomb. Gingko eggs, those stinky orange berries that litter the sidewalks, are embedded throughout the installation, while the acid yellow-green of the tree’s fallen leaves is used to temper the carceral severity of some pieces—for instance, a twenty-foot-tall painting of jade grid-like squares overlaying what looks like smashed concrete, or perhaps cracked tree bark.

Mimosa Echard: Facial, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Amant. Photo: New Document. Pictured, far left: Lady’s Glove (NYC), 2025.

Opposite this behemoth is a canvas a tenth of the size decked out in a curtain of glass beads, anti-radiation fabric, and sundry seductive eyes. Like flatter versions of Joseph Cornell’s memory boxes, Echard’s tableaux are works of surrealist compression in which the history, plastic dreams, and paranoid nightmares of a fluttering cityscape are metabolized to create unique organisms. In a looping video at the end of the show, Times Square is captured in extreme close-up to look almost like a flicker film, its Jumbotron advertisements whittled down to bouncing digital grains.

Mimosa Echard, Tide, 2025 (still). Courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel.

Despite the show’s metropolitan breadth, Echard also folds herself into her practice, aligning its urban rover’s point-of-view with that of her own. Escape more, after all, invites (though ultimately obstructs) the voyeur’s gaze into her personal territory; and Echard’s monograph Lies (2025) is in part a collage of loosely associated images from her ramshackle adolescence in the country and the iconography of ’90s and 2000s commercial culture—especially the aesthetics of Y2K hyperfemininity—that inevitably filtered through her consciousness during those impressionable early years. (Echard was born in 1986.) In Facial, there is a photograph of a woman, perhaps in East Williamsburg, with her back turned away from the camera as she leans over a table and assembles a piece. One of her legs is marked by a slash of glittery depilatory wax and her ass, bare save for a striped thong, is at the center of the frame. Across the room is a massive metal phone charm, Lady’s Glove (NYC) (2025), whose name might refer to the accessories of high-society women or the purple, trumpet-shaped flower. Both conjure Echard: as urbane artist; leaky, libidinal human woman; and purveyor of kitsch drawn from the recesses of her own girlhood.

Beatrice Loayza is a writer and editor who contributes regularly to the New York Times, the Criterion Collection, Film Comment, the Nation, and other publications.

A material girl in a material world: hyperfeminine stylings commingle with industrial structures and materials in the artist’s exhibition.