A new fossil fish suggests that the largest group of freshwater fish began in the sea, not in rivers. These fish include more than 10,000 species, from river giants to tiny aquarium favorites.

The key fossil is a tiny skeleton that was unearthed in ancient river deposits in Alberta, Canada. An international team used its tiny ear bones to redraw a major chapter of fish evolution.

The work was led by Juan Liu, a paleontologist at the University of California, Berkeley. Her research focuses on how fish hearing evolved and how it relates to the diversity of freshwater species.

Textbooks long assumed that otophysans, a huge group of hearing specialist freshwater fish, arose in rivers on the ancient supercontinent Pangea.

By combining the fossil with DNA from living species, the study points to a marine origin about 154 million years ago.

The work also shows that there were at least two separate moves from salt water into rivers and lakes.

One lineage led toward modern catfish and tetras, while another produced carps, minnows, suckers, and model species such as zebrafish.

A tiny fossil with a big story

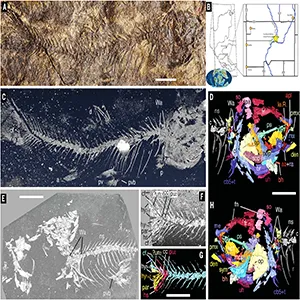

The new species, Acronichthys maccagnoi, lived in a freshwater system about 67 million years ago in what is now Alberta.

Its body was only about two-inches long, yet the skull preserved delicate ear structures rarely seen in fossils.

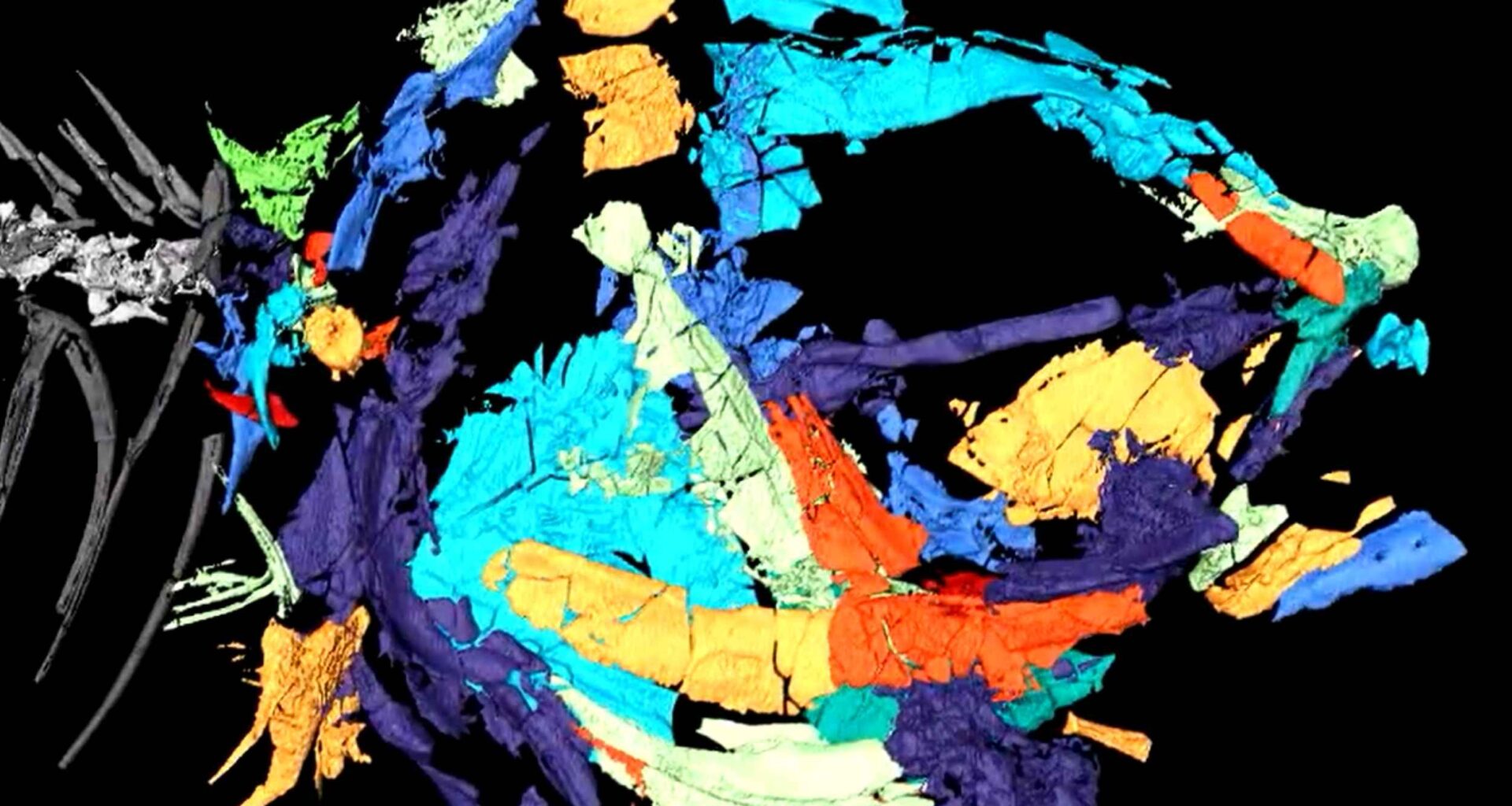

Researchers used high resolution X-ray micro CT scanning to build a 3D model of the fish’s head and vertebrae.

That model revealed a clear Weberian apparatus, a chain of tiny sound carrying bones, linking the fish’s air filled bladder to its inner ear.

“We weren’t sure if this was a fully functional Weberian apparatus, but it turns out the simulation worked,” Liu said.

Her team’s reconstruction suggests that this Late Cretaceous fish could detect mid range sounds in the same way as many modern otophysan species.

Ears and freshwater fish hearing

Hearing in water works differently from hearing in air, because water and fish bodies have similar density.

Most fish have an internal air filled swim bladder, a buoyancy organ that also responds to sound, which vibrates when nearby noise changes pressure.

In these fishes, the Weberian apparatus links the swim bladder and ear so that small pressure changes become stronger signals for the brain.

Otophysans dominate fresh waters worldwide and account for about two-thirds of freshwater fish species, as research on fish hearing also notes.

Zebrafish, one of the best known otophysans in laboratories, use this system to hear a wide band of frequencies.

Electrophysiology, a technique that records nerve signals, has found adults reacting to tones up to 12,000 hertz in tests, as a review reports.

Marine origins and freshwater radiations of the otophysan fishes. Photograph, x-ray image, 3D segmentation, and locality map. Credit: Science. Click image to enlarge.Simulating ancient hearing

Marine origins and freshwater radiations of the otophysan fishes. Photograph, x-ray image, 3D segmentation, and locality map. Credit: Science. Click image to enlarge.Simulating ancient hearing

Liu tests how bones respond to sound using finite element analysis, a computer method that simulates structural vibrations, in living and fossil fish.

Earlier work on zebrafish Weberian ossicles showed that their chain resonates near 900 hertz, as an analysis of their vibration patterns found.

The same modeling approach applied to Acronichthys maccagnoi suggests that its Weberian chain responded best to sounds between roughly 500 and 1,000 hertz.

That peak sensitivity matches hearing ranges in many living relatives, meaning a modern style middle ear already existed before non-avian dinosaurs disappeared.

Developmental work in zebrafish shows that the Weberian apparatus locks into the skeleton before big gains in hearing appear.

This pattern comes from a detailed paper that tracks both bone growth and hearing sensitivity through early life.

Similar patterns appear in catfish, where complete Weberian ossicles correspond with sudden jumps in sensitivity at both low and high frequencies.

One study on developing catfish ears found hearing improved most once the full chain between swim bladder and inner ear had formed.

Freshwater fish lessons from otophysans

Liu’s fossil based timeline suggests that marine ancestors tried freshwater habitats more than once, and that these repeated moves opened many evolutionary paths.

“These repeated incursions into freshwater at the early divergence stage likely accelerated speciation,” she said.

Today that history helps explain why rivers and lakes packed with otophysan fishes host loaches, barbs, electric knifefish, and schooling characins side-by-side.

Understanding how their hearing systems evolved also matters for conservation, because underwater noise and habitat change can threaten species that rely heavily on sound.

This marine origin scenario means that the largest group of freshwater fish descend from ancient ocean dwellers that carried a powerful hearing toolkit inland.

As paleontologists uncover fossils and add them to hearing models, the story of how fish entered fresh water and refined their ears will sharpen.

The study is published in Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–