Over the past 25 years, artificial neural networks have exploded in size, expanding from 60,000 parameters in 1998 (LeNet) to 70 billion in 2024 (Llama 3). Computational neuroscience has benefited from these large models’ ability to solve complex tasks, such as image recognition, and the fact that artificial networks can be used to develop tools and concepts for investigating animal brains.

But as we scale our models up in size and complexity, we risk making the same mistake as the map makers from Jorge Luis Borges’ short parable “On Exactitude in Science,” who created a map of their kingdom that was so detailed it became as large as the kingdom itself —a perfect “model” with no practical use.

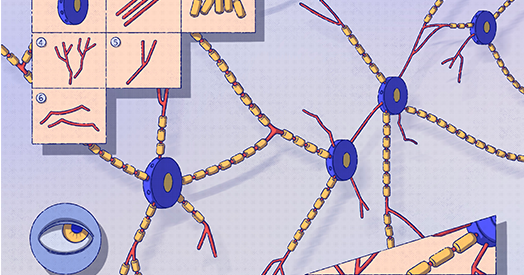

By contrast, smaller models—with, say, two to three neurons—offer a highly interpretable and practical framework for studying neural circuits. Amid the rise of billion-parameter models, these “toy” models have fallen out of favor; some researchers dismiss them as oversimplifications, irrelevant for studying the brain’s complexity. Yet, by providing a springboard for developing theories and benchmarking methods, tiny models have made huge contributions to our understanding of the brain. Here, I argue that toy models remain essential and may even be all neuroscience needs.

T

oy models have a long and successful history in neuroscience. In 1943, Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts used models with one to three hidden (neither sensory nor motor) neurons to demonstrate how neural circuits could implement logical functions, such as determining when one input but not another was active. In a similar vein, almost 80 years later, Anthropic used networks with 2 to 40 neurons to explore when neurons learn to respond to multiple unrelated inputs, a phenomenon called superposition. These works illustrate how toy models have helped develop our understanding of larger systems.

Most neuroscientists, however, are interested in less abstract problems along the lines of how neural circuits generate behavior, such as a cat’s creep or an octopus’s undulations. Currently, much of neuroscience, especially computational neuroscience, does not work at this level of behavioral complexity. Instead, many researchers focus on psychophysics tasks, which reduce complex behaviors down to their core elements.

If our goal is to understand the brain, instead of creating maps the size of kingdoms, we should craft creative, concise toy models.

To study how animals collect evidence and make decisions, for example, many researchers get observers (animals or models) to make sequences of binary choices (such as pulling one of two levers, each associated with a different reward) or to press a button in response to a flash of light or a burst of sound. Recent work has revealed that many tasks like these can be solved by tiny artificial neural networks with just one to four neurons, or even networks in which the neurons connect only to themselves.

These studies suggest that toy models may be all we need for toy tasks, or those in which we reduce the complexities of the environment down to binary pixels and the freedom of movement down to a binary choice. Which raises a provocative question: Is it useful to study complex models solving toy tasks?

As a case in point, researchers recently used an LLM to model human behavior in simple psychophysics tasks, such as pressing a button in response to one color but not another, using prompts such as “You see colour1.” Their model, called Centaur, contains more than 70 billion parameters. To provide a sense of scale, if we take the number of neuron-to-neuron connections as a measure of size or complexity, Centaur is approximately 10 million times larger than a roundworm and 1,000 times larger than a fruit fly, two commonly used animal models. (That said, biological circuits include many “parameters” beyond neuron-to-neuron connections, such as adjustable thresholds and signaling speeds, so these numbers probably overstate this difference. But they still provide an approximate sense of scale.) Though no one expects roundworms or fruit flies to annotate code or perform long division, they do exhibit many of the behaviors that psychophysics tasks aim to model, including making decisions and learning from rewards. Following Borges’ analogy, this makes Centaur like a map of a kingdom, larger than the kingdom itself.

W

hat can we learn from such large models? Because we can observe and manipulate each of Centaur’s connections or neurons however we like, it should be easier to study than an animal model. Researchers in NeuroAI would argue that these models are ideal for developing experimental methods or analysis tools, which can later be applied to real brains. However, as we lack a ground-truth understanding of how these complex models work, it can be hard to tell if our tools provide meaningful insights.

Toy models rectify this by being highly interpretable yet, in many cases, still amenable to the same manipulations and analysis. If our goal is to develop new methods, we should start with toy models and then build complexity from there. Conversely, if experimental methods or analyses fail in toy models, then it can be hard to imagine how or why these problems would vanish at scale. For example, one of my favorite papers used a tiny artificial neural network (with a single hidden neuron) to demonstrate that silencing one neuron, or even one connection, at a time, would not produce an accurate understanding of how a network works. Instead, the researchers propose a method for silencing different combinations of elements, which would have been challenging to develop in a complex model. Though, more recently, the researchers applied their multi-lesion method to a huge 56-billion-parameter model, demonstrating the value of starting small and then scaling.

So are toy models all neuroscience needs? There are phenomena that only emerge at scale and that could not be studied in the smallest toy models, such as how the layers in deep visual networks seem to represent increasingly high-level features, from edges to shapes to objects. And neuroscientists are increasingly working with more challenging, naturalistic tasks, which toy models would struggle with. But even in these cases, for our models and theories to remain interpretable, they should be as simple as possible. If our goal is to understand the brain, instead of creating maps the size of kingdoms, we should craft creative, concise toy models.