Driving a taxi in the Russian capital was never very lucrative for Said, a Tajik migrant living in the Moscow region, but it paid the bills.

Now, he says, gasoline has jumped by more than 30 percent in recent weeks – from 45 rubles a liter to 60. All told, his daily take-home pay is just three-quarters of what he used to net, he says; he can barely cover living expenses.

“You work, and you pay your rent, and you pay for your gas — those are all your expenses,” he told RFE/RL, asking only to be identified by his first name.

And the Russian capital isn’t the only locality seeing a spike. “Seems that Russia is on the brink of a full-scale fuel crisis,” one of Moscow’s largest tabloid papers declared last month, pointing to growing number of regions reporting shortages and price hikes.

The shortage is blamed mainly on a decidedly non-economic factor: a targeted drone campaign by Ukrainian forces that’s knocked out as much as 17 percent of Russia’s refining capacity.

But it’s rattling Russian consumers who are increasingly feeling the effects of a broader slowdown. After years of torrid growth, propelled by government spending to fuel the war on Ukraine, Russia’s economy is grinding to a crawl.

For the central bank, which is struggling to tamp down soaring inflation, the hope is this will help rebalance the economy. For the Kremlin, the hope is the slowdown does not erode support for the Ukraine war.

“The crisis is ongoing, it is developing, it is growing, it is intensifying,” Igor Lipsits, a Russian economist, told RFE/RL’s Tatar-Bashkir Service.

“And it is becoming impossible to hide it completely, and lying completely is also not good, because then suddenly the population will wake up and say: ‘Why didn’t you tell us that the situation in the country is bad’?”

For other economists, the deceleration is neither critical nor unanticipated.

“This is the expected slowdown in growth. Currently, it looks very much like a soft landing, not an acute crisis of any sort,” said Laura Solanko, an economist at the Bank of Finland’s Institute for Emerging Economies.

Economic Downshift

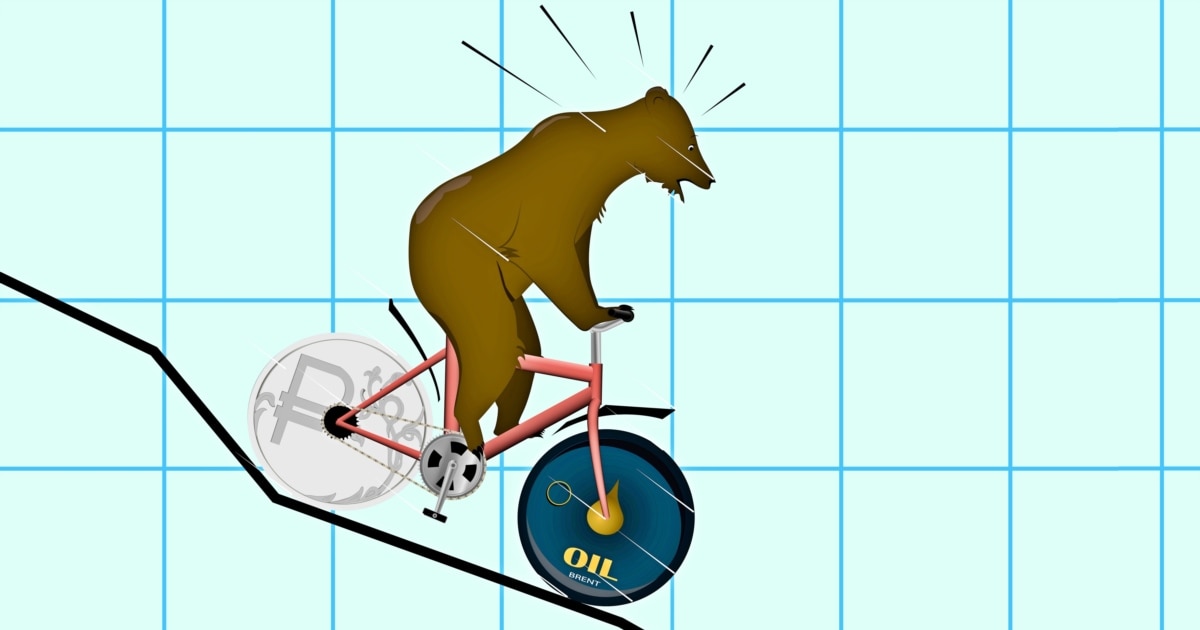

For more than two years now, Russia’s economy has chugged forward like a truck that has a powerful engine but wheels that are increasingly out of balance.

The truck itself is the product of a national industrial retooling aimed at waging war on Ukraine. Fueled by foreign oil and gas sales, the Kremlin has pumped the economy full of rubles, prioritizing the production of tanks, guns, shells, drones, uniforms, and equipment for soldiers.

Total spending on defense and security reached 41 percent of all spending in 2025, according to government figures — the highest it’s been since the Cold War.

To keep the ranks fully manned, meanwhile, the government has paid out extraordinarily high wages and benefits to entice men to volunteer to fight.

That’s flooded Russia’s poorer regions with cash, but it has also distorted labor markets, pushing up wages and pushing inflation to nearly 10 percent.

That in turned prompted the Central Bank to hike lending rates — which influences things like car loans and mortgages — to tamp down inflation.

The result?

In the first three months of this year, GDP dropped 0.6 percent compared the previous three months. That’s the first contraction since 2022, when, amid a battering by Western sanctions and Western companies pulling out of the country in the wake of the invasion, the economy contracted 1.4 percent.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s top advisers have publicly warned of a slowdown. Finance Minister Anton Siluanov told Putin that that the economy would grow just 1.5 percent.

Days later, Economics Minister Maksim Reshetnikov warned the economy was “cooling down faster than expected.”

German Gref, who heads state-run banking giant Sberbank, warned of possible “stagnation.”

Putin has tried to tamp down fears of wider slowdown.

“I’m certain that in the end we’ll succeed in resolving the issues, to support the necessary pace of economic growth while keeping inflation at a minimum,” he said during a business forum in Vladivostok.

“Everyone also understands that if inflation overwhelms the economy, it will not end well.”

Guns, Not Butter

“So, what comes next will be stagnation — essentially zero or 1 percent growth — and then a recession will follow,” said Bogdan Bakaleyko, a former Russian journalist and economics commentator.

If stagflation or recession results in an uptick in unemployment, Bakaleyko said, it would potentially push more people to fight in Ukraine to take advantage of wages and benefits being offered by the Defense Ministry.

Russians “will either be without money, without a job, and without food, or they’ll sign a contract with the Defense Ministry because there will always be money for that,” he told Current Time.

“So economic problems actually play right into Vladimir Putin’s hands.”

Adding Insult To Injury

For Russian budget officials, the slowdown puts pressure on the government budget, which is already facing a deficit on track to hit 5 billion rubles ($62 billion) in 2025. But the Kremlin has shown no signs of wanting to cut back on war spending.

Last month, the Reuters news agency, citing unnamed officials, said tax increases were inevitable.

“Russia’s capacity to maintain its wartime footing relies heavily on oil prices and the trajectory of the sanctions regime,” the Peterson Institute for International Economics said in a report last month.

“If Russia suffers setbacks on the battlefield while grappling with constrained resources, it may be compelled to adjust its approach, either by scaling back its offensive or showing greater openness to negotiations.”

Vladislav Zhukovsky, an independent economist, predicted a hike in the value-added tax, which was last increased in 2019 — just months after Putin was re-elected to his fourth term.

“This is the most predatory tax, the most strangling for the economy and the population, because it is collected, so to speak, from all economic activity — from all production and demand within the country,” he told Current Time.

“This will undermine Russian industry, civilian industry, because they will simply be forced to shift these production costs…to the end consumer,” he said.

“As a result, prices will skyrocket by at least 10-15 percent on top of that. For the population, this is a blow to the wallet, a drop in the standard of living, in the real purchasing power of the population.”

With reporting by Current Time, RFE/RL’s Tatar-Bashkir Service and the Central Asian Service