George Washington is lionized as a general and president.

But to Northeastern University historian William Fowler, perhaps the greatest insight into Washington’s role as the “father of his country” comes not from accomplishments on the battlefield or behind his presidential desk, but from the years in between at his Mount Vernon home.

“I was very interested in what this man was doing from the end of the Revolution until he traveled to New York to take the oath of office,” says Fowler, distinguished professor emeritus of history at Northeastern. “Was he just sitting at home? Was he just talking to his grandchildren? Was he just overseeing his plantation? I was curious, and that is what drives historians.”

Fowler is the author of nearly a dozen books on American history, including “The Baron of Beacon Hill: A Biography of John Hancock,” “Samuel Adams: Radical Puritan,” and “Rebels Under Sail: A History of the American Navy in the Revolution.”

His latest book, “George Washington and the Creation of the American Republic,” was released this month.

Fowler says the book arose from his wish to “continue the story” from his previous book, “American Crisis: George Washington and the Dangerous Two Years After Yorktown, 1781–1783.” As such, the new book covers the time between the end of the Revolution in 1781 and the beginning of Washington’s presidency in 1789.

“He took the presidency at probably the most tumultuous period in American history,” Fowler says.

But Washington was a “unifying figure,” Fowler says.

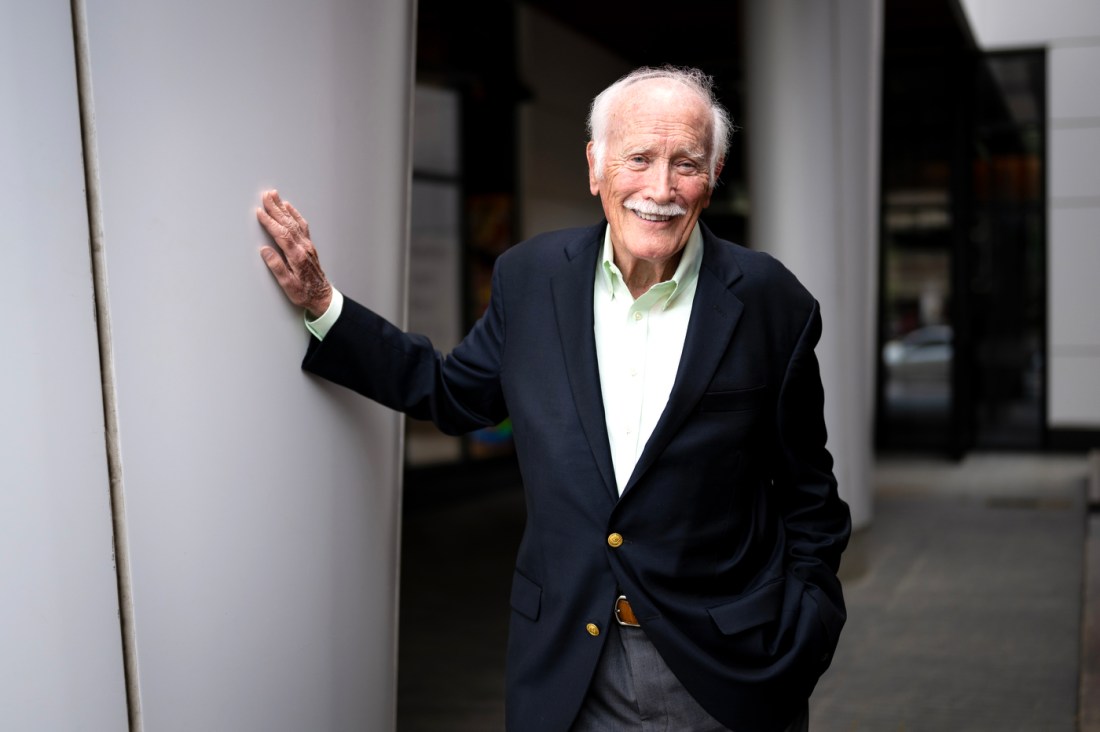

Fowler focuses his book on Washington’s life from the end of the Revolutionary War to the beginning of his presidency. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

Fowler focuses his book on Washington’s life from the end of the Revolutionary War to the beginning of his presidency. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

“He was a man of virtue. He was a man of consistency. He was physically brave. Sometimes wrong, but he could admit to his failures,” Fowler says. “He was greatly admired by nearly everyone who knew him or saw him or served him from the lowliest private in the American Revolution to the members of his own Cabinet.”

Washington was also incredibly well attuned to the forming nation.

He had traveled widely as a land surveyor and soldier and, even after the Revolution, traveled as a land speculator in the West and a respected figure throughout the future nation.

“I suspect you can go through any number of towns — especially New England towns — and find a sign that says ‘Washington slept here,’” Fowler quipped.

Moreover, hundreds of people a year came to visit Washington at Mount Vernon — so many people, in fact, that Washington likened his home to an “inn” or “tavern,” Fowler says.

“He saw, probably, more of America in his lifetime than any other American, and more Americans visited him than any other American,” Fowler says. “He was the center of this forming, yet-to-be-created nation.”

But this future nation also “troubled him,” Fowler says.

“What troubled him was that the ‘nation’ — and I use that in quotation marks — that he had helped to create, was not fulfilling its destiny. It was, in fact, in danger in some places of falling apart.”

So, Washington put himself forward to be the new leader of the nation at the Constitutional Convention.

“He was the unifying theme,” Fowler says. “He settled us down at a time when we could have gone in fractious, different ways.”

Not that the carefully cultivated image of a statesman and austere general on an (always) white horse was Washington’s whole persona.

“He, in a sense, lived two separate lives,” Fowler says. “We see him, in a political sense, as this austere, staid, distant person, and he was. But then there’s this other side — the social George. And the social George was convivial, loved a good joke — he was a loving grandfather, a good friend, a damn good farmer, and loved a good time.”

Fowler also notes that the fact that Washington was a slaveowner cannot be ignored.

“Slavery is his greatest flaw — there’s no question about that,” Fowler says. “Some historians have said that he was uncomfortable with slavery. I never really found any evidence of that. He was a southern plantation owner. That kind of says it all.”

But Washington was also modest — as he would demonstrate in stepping aside after his second term.

“As president, the world changes — it’s now a republic, it’s now that political parties are emerging, national issues are emerging, we’re into the problems with the French, continuing problems with the British — the world really becomes much more complicated,” Fowler says. “I do believe that in great measure Washington knew, he knew what he had done and he knew what he couldn’t do, and he knew the world in which he had lived and done amazing things wasn’t the same world now, and it was time for him to retire.”

“He’s so different,” Fowler adds. “We’ve had many presidents, many leaders, I suppose,

whose careers and whose stories are always a little bit muddled.”

“Washington has an amazing consistency,” Fowler continues. “It’s a consistency of dignity and honor and service.”

University News

Recent Stories