Panic attacks among Kashmir students are rising due to stress, stigma and poor institutional support, with experts urging awareness, counsellors and early intervention, reports Afreen Ashraf

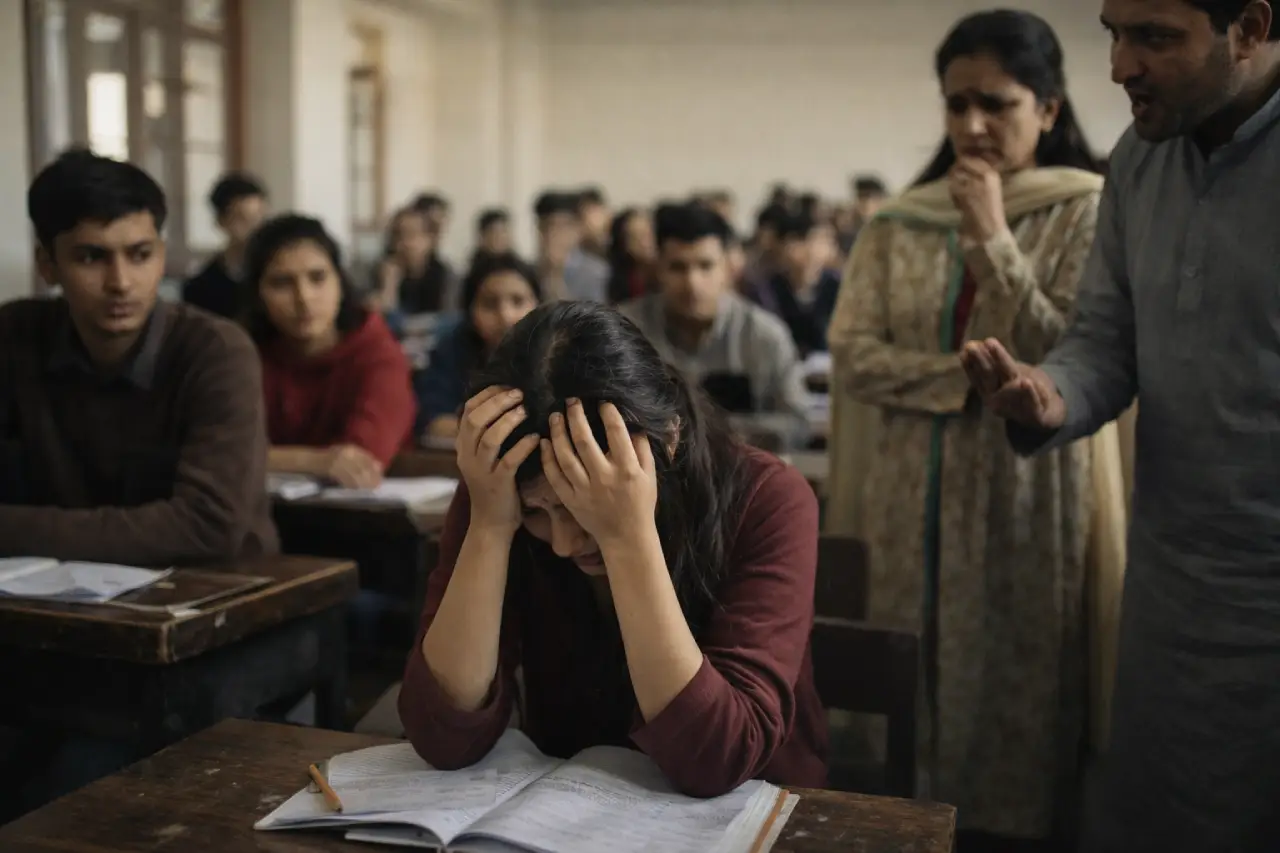

Panic Attack in a classroom, an AI imagination

Panic Attack in a classroom, an AI imagination

Manat, a third-semester BA student currently undergoing counselling, recalls her first anxiety attack as a terrifying experience. “The only thought I had at that moment was Malakul Mout is upon me,” she recalled. “I felt like my soul was leaving my body. My unawareness made the situation worse.”

What Manat experienced was a panic attack, something she did not recognise then. A psychiatrist working with young patients in Kashmir explained that panic attacks are often the body’s response to prolonged, unaddressed stress. “Among youth, panic attacks usually do not come out of nowhere,” the psychiatrist said. “They are the result of academic pressure, uncertainty about the future, social isolation, and exposure to ongoing stress. The body reacts before the mind fully understands what is happening, which is why many young people mistake panic attacks for physical illness or fear they are dying.”

Classroom Panics

Manat’s case is far from isolated. Across Jammu and Kashmir, students in schools and colleges are increasingly reporting panic attacks, anxiety and emotional breakdowns. Many of them struggle without understanding what is happening to them. Experts warn that inadequate mental health infrastructure, lack of trained professionals, and social stigma have left young people dealing with distress largely on their own, while educational institutions remain ill-equipped to respond.

Mehdi Ali lives in his college hostel. He has witnessed similar episodes among his peers. “I have seen students break down in washrooms at night,” he said. “Some experience sudden breathlessness or chest pain but don’t know it’s anxiety. Most of us don’t talk about it openly because we are scared of being labelled weak or unstable.”

Such episodes are rarely recognised as mental health emergencies within educational institutions. According to Dr Nadia, educational environments can unintentionally intensify panic symptoms. “Young people today are under constant performance pressure, but they lack emotional spaces to process failure, fear, or uncertainty,” she said. “When stress is normalised and emotional expression is discouraged, anxiety gets internalised. Panic attacks are often the breaking point, not the beginning of the problem”. Instead of treatment, she said, affected students are often advised to “stay strong” or “ignore the stress,” responses that deepen their distress.

Dr Altaf Pal is In-charge of the Counselling Cell at Amar Singh College, Srinagar. He admits the scale of psychological distress among students is alarming. “Based on my experience and regular interactions with students on campus, I can say without hesitation that if a college has 100 students, nearly 30 to 40 of them would require counselling support,” he said, asserting every single word.

A cross-sectional survey conducted between January and April 2024 among 1,471 college students aged 18 to 26 across institutions in the Kashmir division supports these observations. The study, Depression, anxiety, and Stress Among College Students: A Kashmir-based Epidemiological Study, carried out by a group of psychiatrists and published in Frontiers, found that 12.5 per cent of participants exhibited severe depression, with a slightly higher prevalence among females (13.39 per cent). Severe anxiety was reported by 24.26 per cent of students, while 19.17 per cent experienced high levels of perceived stress.

Inadequate Support

Despite the rising numbers, mental health infrastructure within educational institutions remains inadequate. “Our college lacks proper facilities to accommodate students seeking counselling, admitted Pal. “We work alongside the college health committee, but the counselling cell is largely run by professors who are not professionally trained to handle mental health cases, which makes these services less effective.” He adds that effective counselling requires a separate, private space to ensure confidentiality, something our colleges lack.

At the school level, mental health support remains even weaker. Limited awareness and lack of training among teachers often result in early symptoms being overlooked. A study conducted across 16 schools in Srinagar and Ganderbal found high levels of academic stress among students from classes 9 to 12, with many experiencing anxiety and depression. Of the 97 students identified with psychiatric morbidity, nearly 70 per cent were aged between 13 and 16 years.

Aneesa, now a Class 10 student, recalls experiencing her first panic attack in 2022. After reporting breathlessness to her class teacher, she was taken to the medical room and asked to rest. As her condition worsened, she was scolded for being “dramatic”, which only intensified her distress. “I don’t blame my teacher,” Aneesa said. “She looked as unprepared as I was. Maybe she was not used to dealing with a student in such a condition. She seemed panicked.”

Similar incidents are reported at the college level. “One of my classmates started crying during class and said she couldn’t breathe. The teacher scolded her and told her to stop acting. Later, we found out it was a panic attack,” another student recalled.

Such responses highlight how the lack of awareness and training among educators contributes to the crisis. Dr Nadia notes that panic attacks are frequently misunderstood because they resemble disciplinary or behavioural issues. “Symptoms like breathlessness, crying, restlessness or inability to sit still are often misread as misbehaviour or attention-seeking. In reality, the student is experiencing an intense physiological response driven by fear. Without basic mental health literacy, teachers may unintentionally worsen the episode.”

Dr Pal warned that without dedicated mental health professionals and clear support mechanisms, students may hesitate to approach counselling services. “When systems are weak, distress often goes unaddressed until it becomes severe,” he said. Mehdi also spoke about this concern. “There is no counsellor in the hostel. If something happens, wardens usually tell us to calm down or call home. Some even think students are creating drama. There is no proper system to handle mental health emergencies,” he asserted.

Surging Gulf

The situation is aggravated by a severe shortage of mental health professionals at the state level. Jammu and Kashmir has only 0.75 psychiatrists per 1,00,000 people, far below the World Health Organisation’s recommended level, severely limiting access to care.

Social stigma remains one of the strongest barriers preventing students from seeking help. Many fear being labelled “weak,” “unstable,” or pagal, forcing them to maintain silence. Mehdi explained how mental health conversations are discouraged among peers. “If we speak about these things, we are immediately labelled as chapri,” he said.

Dr Tabinda, a psychologist at JVC, said that fear of judgment and apathy continue to dominate student behaviour, discouraging them from coming forward.

Manat shared that she delayed seeking professional help for months due to fear of being judged. “I thought people would call me mad,” she said. That worsened her condition, highlighting the real cost of silence driven by stigma.

Speaking about coping and recovery, Dr Marya Zahoor from IMHANS emphasises early intervention and support. “The most important step is recognition. Panic attacks are not a sign of weakness or madness,” she said. “When young people understand what is happening to them and are guided through breathing techniques, reassurance, and counselling, symptoms can be managed effectively. Ignoring or suppressing these episodes only increases their intensity over time.”

Earlier Studies

Studies have pointed to the seriousness of the issue. A 2019 study by Paul and Khan published in The International Journal of Indian Psychology found that the prevalence of mental disorders among school-going children in Kashmir is significantly higher compared to other states. Yet awareness remains limited.

Many students admit that they initially avoided seeking help simply because they did not understand what they were experiencing. “I thought maybe I am overreacting,” one student admitted, asserting he was in self-disbelief.

While the government has taken steps to address the crisis, including the launch of the Tele-MANAS mental health helpline in 2022, gaps remain. Although the service has received over 90,000 calls from Jammu and Kashmir, many students remain unaware of its existence. “This service is still largely unknown among students,” admitted Dr Pal.

Experts caution that helplines alone cannot address the crisis. Tabinda recounts the case of a young girl who showed improvement only after her family was actively involved in therapy. “Mental health problems cannot be treated individually. They require a collective response,” she said. Families, educational institutions, healthcare systems and the government must work together. “People in Kashmir need to understand that mental health problems require care just like any physical illness.”

Similar concerns were expressed by a college counselling cell in charge. “As almost half of our youth is suffering, we need to look into this seriously. These students are our future. They need timely help, proper counselling and systems that protect them,” he says.

Students themselves articulated these demands. “At least one trained counsellor, awareness sessions, and a safe space where students can talk without fear is needed. Most of us don’t want sympathy; we want understanding,” the student said.

For many students in Jammu and Kashmir, mental health distress is no longer hidden. It plays out daily in classrooms, hostels and examination halls. Panic attacks, anxiety and emotional breakdowns increasingly affect how students study, attend classes and cope with academic pressure, often without being recognised or addressed.

The experiences shared by students reveal a troubling pattern where stigma, lack of awareness and institutional unpreparedness force young people to carry their struggles alone. Experts warn that without timely intervention, untreated distress can evolve into more serious psychological conditions, affecting both education and well-being.

While initiatives like Tele-MANAS have opened new avenues for support, the gap between policy and practice remains wide. Addressing the mental health crisis among students requires sustained investment in counselling services within educational institutions, training teachers to respond sensitively, and a broader cultural shift that treats psychological distress as a health concern rather than a personal weakness. Until schools and colleges become spaces of care alongside learning, the silent burden carried by the region’s youth is likely to continue.