China is one of the world’s biggest photography markets, even besting the Americas in terms of camera and lens sales earlier this year. However, China’s rich photographic history is not well known in the West, something American photographer Ben Fraternale, who runs the excellent photography YouTube channel “In An Instant,” hopes to change through his new three-part documentary series, “Inside China.”

In the first episode of “Inside China,” which premiered on YouTube this week, Fraternale explores Shanghai and Beijing to see how photography has evolved in China over the years and what modern-day Chinese photographers are doing to embrace and push the medium forward. For the gearheads out there, Fraternale also dives into China’s vast used-camera market to uncover some of the country’s best gems.

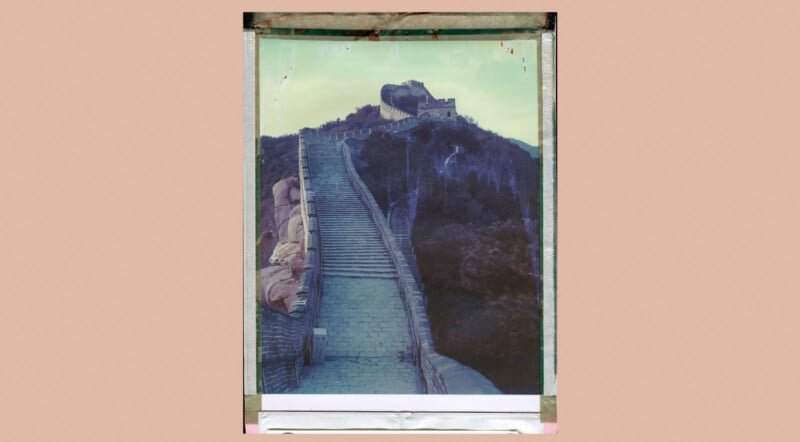

How Fraternale even decided to embark on this massive endeavor to uncover and celebrate China’s photographic history is quite interesting in and of itself. Fraternale received an email from photographer Lin Weijian, or Jesse Lin, who operates a Polaroid 20×24 Studio in Shanghai. Weijian was the first person in China to open such a studio, building upon the groundbreaking work John Reuter started in the early 21st century in the United States.

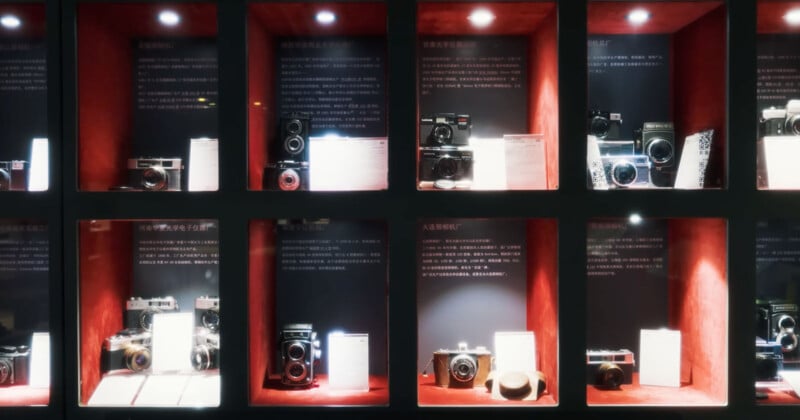

But before visiting Weijian’s studio or checking out China’s camera market and contemporary photographers, Fraternale had to start where all good stories do: the beginning. At the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Shanghai, Fraternale got the breakdown from the museum’s historian.

Very shortly after Louis Daguerre unveiled the daguerreotype process in France in 1839, photography reached China. The museum explains that there are silver plates from the 1840s that were captured in China. However, photography didn’t take off super fast in China, as there were concerns among people at the time that a photograph could capture your soul, a fear certainly not unique to China.

As photography gradually became accepted throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, it remained a luxury for many. It took a long time for photography to be used to capture everyday life, let alone become an art form, in China. Even well into the late 20th century, as China underwent significant change, cameras and photography were inaccessible to everyday people.

In the late 1950s, the new communist government in China approved the production of domestic photographic film and products to help reduce the cost of photography for more people. A famous company to arise from this was China Lucky Film, which just last year revived its color film production efforts.

There were also, of course, many other Chinese photography companies and Chinese camera brands, perhaps the most famous of which is Seagull. Fraternale, scouring Chinese film and camera shops, scored a used 1950s-era Seagull 4B TLR for himself for less than $100.

“We did it, we got a beautiful Seagull 4B, one of the most renowned cameras of Chinese photographic history,” a very pleased Fraternale says.

China’s photography companies primarily focused on mimicking foreign cameras for decades, aping cameras from companies like Leica, Agfa, Polaroid, and, in the case of Fraternale’s Seagull, Rolleiflex. While this worked for a long time, once China opened its borders to foreign camera companies, like Canon, Nikon, Fujifilm, and Leica, to name just a few, state-owned photo companies like Seagull could no longer keep up. While the company is gone, its legacy is not. A technician from Seagull works at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Shanghai, maintaining and repairing old Seagull cameras in a preserved machining area.

Although many Chinese analog photography companies are no longer operating, China’s photography scene, like the rest of the world, has seen a significant resurgence of analog photography in recent years. Young photographers in China are buying old film cameras in droves and embracing the analog experience.

And of course today, there are still many Chinese photography companies, albeit different ones. Chinese lens makers like Viltrox are doing a ton of interesting things and making exceptional optics.

This brings the story to Polaroid and how instant photography landed in China and took off, which Fraternale covers at the end of the video above. But there is much more to the story of photography in China, which Fraternale will cover in a pair of upcoming episodes.

Image credits: Ben Fraternale (In An Instant)