A brilliant cosmic flash, brief yet immensely powerful, travelled over 13 billion years before reaching Earth. It passed through a universe that was still young, turbulent and dark, long before galaxies like our own had taken shape. The burst was only ten seconds long.

Its origin was not immediately clear. But as data accumulated from space- and ground-based telescopes, scientists realised they were observing something far older than anything previously confirmed in its class. A collapsing star, perhaps. Or a type of stellar death not yet fully understood.

Signals like this are not uncommon. They are detected, catalogued and studied. Yet this one stood apart. The time it took to arrive, and the way it unfolded, made it different.

By the time its nature was confirmed, it had broken a record. The light came from a supernova that exploded when the cosmos was just 730 million years old. Not only is it the most distant event of its kind ever observed, it may also reshape how researchers think about star formation in the universe’s first billion years.

A Coordinated International Detection

The initial detection occurred on 14 March 2025, when the SVOM (Space-based multi-band astronomical Variable Objects Monitor) satellite, a joint French-Chinese mission, recorded a gamma-ray burst lasting ten seconds. These long bursts are commonly associated with the death of massive stars and the birth of black holes, emitting focused jets of energy that remain visible across vast cosmic distances.

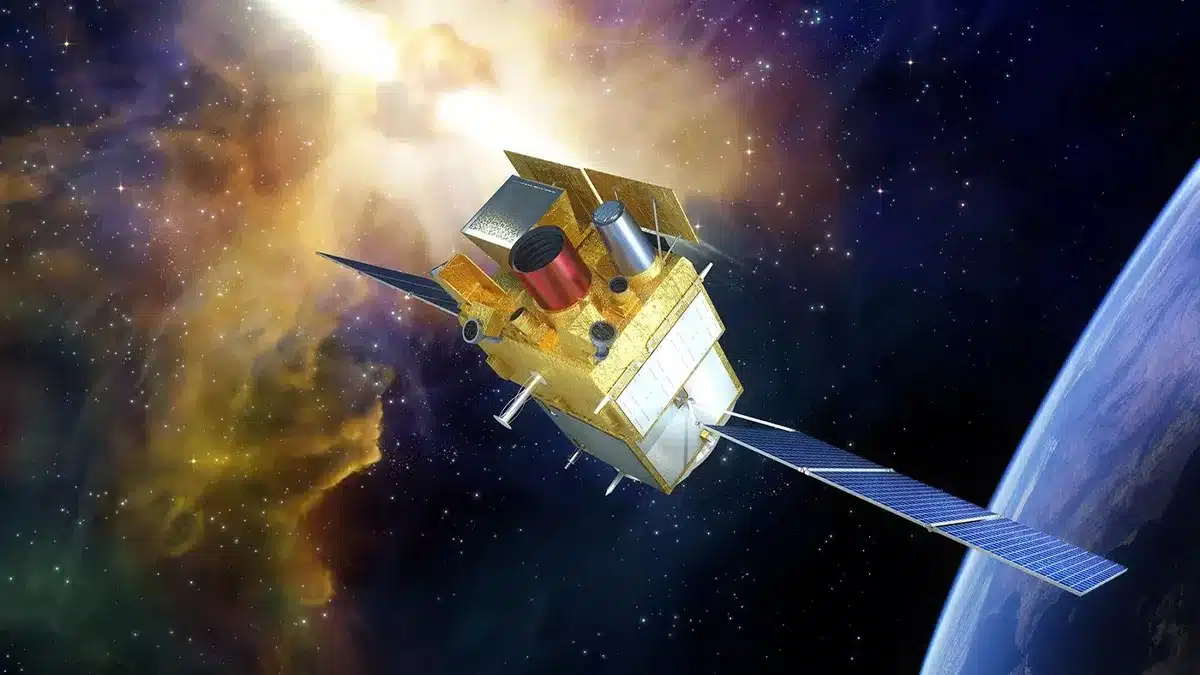

Artist’s rendering of the SVOM (Space-based multi-band astronomical Variable Objects Monitor) satellite. Credit: CNES

Artist’s rendering of the SVOM (Space-based multi-band astronomical Variable Objects Monitor) satellite. Credit: CNES

SVOM’s early success in identifying what was later designated GRB 250314A was notable, as the mission had only recently begun full operations. Researchers from the Observatoire de Paris – PSL and other European institutions confirmed that the burst originated during the Epoch of Reionisation, the era when the first stars and galaxies began ionising the intergalactic medium.

Within hours of detection, NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory pinpointed the gamma-ray source. Follow-up observations by the Nordic Optical Telescope and Very Large Telescope (VLT) revealed an infrared afterglow, allowing astronomers to determine a redshift of 7.3, indicating the light had travelled more than 13 billion years.

The source of a super bright flash of light known as a gamma-ray burst: a supernova that exploded when the Universe was only 730 million years old. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, A. Levan (IMAPP), Image Processing: A. Pagan (STScI)

The source of a super bright flash of light known as a gamma-ray burst: a supernova that exploded when the Universe was only 730 million years old. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, A. Levan (IMAPP), Image Processing: A. Pagan (STScI)

Few gamma-ray bursts have ever been detected from this early in cosmic history. According to the ESA’s mission update, this particular event now holds the record for the most distant supernova confirmed to date.

Confirmation by the James Webb Space Telescope

Three and a half months after the initial burst, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was directed toward the fading afterglow. This delay was not a setback. Because of the expansion of the universe, light from distant objects becomes stretched, a phenomenon known as redshift, and events appear to unfold over longer periods of time.

JWST’s NIRCam and NIRSpec instruments captured images of both the supernova and its host galaxy, confirming that the gamma-ray burst originated from the collapse of a massive star. This marks the first time a host galaxy has been detected for a supernova so distant in both space and time.

This two-part illustration represents supernova GRB 250314A as it was exploding and three months after that when Webb observed it. Webb confirmed the supernova occurred when the Universe was only 730 million years old. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, L. Hustak (STScI)

This two-part illustration represents supernova GRB 250314A as it was exploding and three months after that when Webb observed it. Webb confirmed the supernova occurred when the Universe was only 730 million years old. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, L. Hustak (STScI)

In a peer-reviewed paper published in Astronomy & Astrophysics Letters and cited by the European Southern Observatory and NASA, scientists confirmed that GRB 250314A broke the previous distance record set by a supernova observed at a redshift of 4.3.

“Only Webb could directly show that this light is from a supernova, a collapsing massive star,” said Andrew Levan, professor at Radboud University and lead author of one of the studies.

The team used a rapid-turnaround Director’s Discretionary Time program to ensure the event was observed at peak brightness. Light from the explosion had been stretched across time, so capturing the right moment required precise modelling and timing.

Unexpected Similarity to Modern Supernovae

The results challenged long-standing assumptions. The explosion did not show the unique chemical or energetic traits expected from stars in the early universe, often referred to as Population III stars. These first-generation stars, lacking in heavy elements (or metals), were thought to die in highly energetic and asymmetric explosions.

Instead, data from JWST observations revealed a standard Type II supernova, matching closely with those observed in the local universe today. This suggests that the processes shaping star death, and possibly even chemical enrichment, were already well underway just 730 million years after the Big Bang.

Nial Tanvir, professor at the University of Leicester and co-author of the study, noted: “Webb showed that this supernova looks exactly like modern supernovae.”

If confirmed across additional events, this could indicate that galaxies were evolving faster than previously thought, producing multiple generations of stars in a relatively short cosmological time span.

Implications for Early Cosmic Evolution

The detection of GRB 250314A provides new insight into how quickly complexity emerged in the early universe. With the combined efforts of SVOM, JWST, and other ground-based facilities, researchers were able to confirm both the nature of the explosion and the structure of its host environment.

The discovery also illustrates how gamma-ray bursts can serve as powerful tools for probing the universe’s earliest epochs. Their brightness and distinct signatures allow scientists to trace cosmic events occurring billions of years ago, offering a complementary approach to traditional deep-field imaging.

Researchers involved in the current project have secured additional observation time on JWST to monitor similar high-redshift events. These future campaigns will focus on detecting afterglows and host galaxies, helping astronomers build a clearer picture of early stellar evolution.