One of Liam Cullinane’s toughest tests after joining the French Foreign Legion in 1985 was a gruelling night march near Marseille. Every soldier was weighed down by a heavy rucksack, endlessly trudging through the darkness, each hour slower than the previous one.

“I was not prepared for it. It was exhausting,” he recalls.

And then, some time after dawn, the march finally ended.

“All I had been thinking about throughout the march was going to bed and kip for a few hours.”

To his dismay, he found that it wasn’t over. His more experienced colleagues immediately began preparing to do an equally tough obstacle course.

“I was saying to myself, ‘these guys are fruitcakes’.”

Flaked out as he was, Cullinane had no choice but to continue. As he did it, he realised it was not the endurance test he had expected it to be. He had little difficulty completing it. Afterwards, he reflected on a challenge that should have been torturous but wasn’t.

“It was because I was so boll**ed from marching all night that the pain did not register,” he said. “I was very calm and relaxed afterwards. I felt I could do it again.

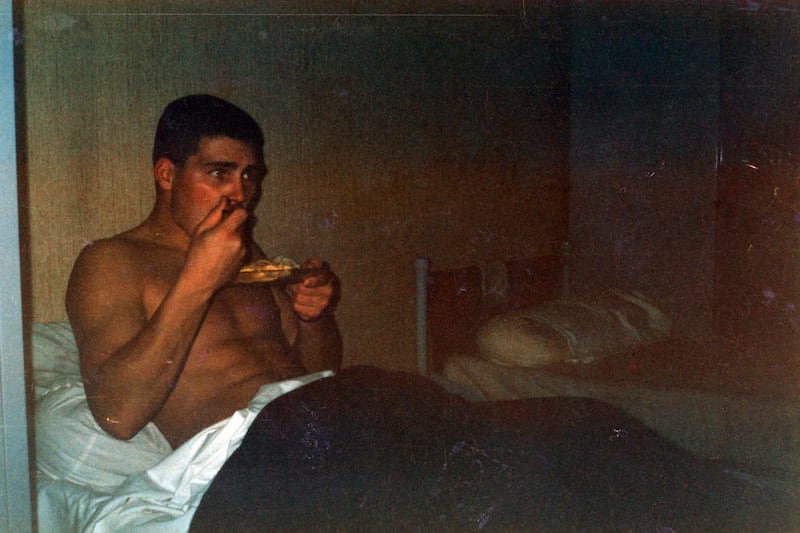

Legionnaire: Liam Cullinane with fellow French Foreign Legion commandos in the early 1990s

Legionnaire: Liam Cullinane with fellow French Foreign Legion commandos in the early 1990s

“It dawned on me [that] when your mind is set on something, your body does not have a choice but to follow.”

Almost eight years later that moment of self-realisation was to be severely put to the test. Cullinane had been demobilised from the French Foreign Legion and led a carefree, peripatetic year, enjoying a physical, outdoorsy life. He spent time in the Himalayas and did an intensive month of scuba diving in the Red Sea. In the depth of that winter, he was doing a professional diving course on the west coast of Scotland.

The course lasted three months. During the final week Cullinane developed a toothache and went to the dentist. But the pain persisted.

“I felt there was a little fellow in my head with a sledgehammer,” he says of the pain. “When I was in the Legion you would not call in sick because your mates would slag you. I thought I’d be grand.”

On a Thursday night, he felt very sick. The headache was bearable as long as he did not move. But when he stood up, it pounded.

Friday was the final day of his course. But he barely made it through the day, vomiting violently at one stage.

He somehow made it back to his apartment. His headache was still pounding but he had to finish his packing. He was going to Edinburgh that evening to stay with his younger brother Harry, who was at university there. Then he would head off on his “next adventure”.

He never made it to Edinburgh. He never made it to his next adventure.

That Friday afternoon in April, 1993, Cullinane collapsed as he entered the shower in the flat. On Monday morning, a cleaner arrived to prepare the flat for the next tenant and came upon him, seemingly lifeless.

He was alive but barely so. For weeks, he lay on a hospital bed in Glasgow, comatose. One doctor monitoring the electroencephalogram (EEG) device observed there was not much sign of brain activity.

When, three weeks after his admission, he finally regained consciousness, Harry was the first person he saw. By the bedside since it happened, it was his big-hearted brotherwho was there to break the devastating news to Liam that he had been through a life-changing episode.

Somewhere between the toothache and the diving and the cold, Liam had contracted a rare form of meningitis. Its full medical name was listeria monocytogenes meningoencephalitis. Its effects were devastating, especially in terms of his spinal cord and the fluid and membranes around the brain.

Cullinane could only move his right arm, was unable to speak or breathe properly and could not control his bodily functions. Initially, he communicated by spelling words out with letters.

After only recently being told I was never going to get up it was amazing. I rang Harry and gave him the news

— Liam Cullinane

The doctors who looked after him in the early stages held out little hope. One of them wrote: “Sadly, our prognosis is that he will remain with significant difficulties, even though he still harbours the hope that with more therapy he will return to the fit, independent young man that he was before.”

From his ravaged body, a story of hope and determination emerged – a refusal to accept there would be no recovery. Cullinane was realistic enough to accept it would never be the same. He felt lucky to be alive. But having been to the brink, he believed he could somehow come back.

[ Meningitis: I always say ‘my mum’s knowledge saved me’Opens in new window ]

To explain Liam Cullinane’s life since April, 1993, it is necessary to delve into his life before that, which was predominantly focused on physical activity. When his trauma happened, it was like a sessile oak tree being felled.

Cullinane was 6ft 3in, dark-haired and strikingly good looking. Born in Edinburgh in 1967, his family moved back to Galway when he was a teenager. He never fully lost his Scottish accent and was nicknamed “Jock” by his schoolmates.

He was in Coláiste Iognáid at the same time as me. Cullinane was taciturn but could be rebellious. By his own admission, he was mediocre academically but excelled in sport, particularly in rugby. From the age of 15, his only ambition was to join the French Foreign Legion.

He did that at the age of 18 when he walked into a recruiting station in Nice. The process was no cakewalk. Besides the physical challenges, there were crash courses in learning French. Cullinane thrived in the environment, finishing in the top 10 in his class. He was assigned to the mountain company of the parachute regiment based in Corsica.

Liam Cullinane joined the French Foreign at age 18

Liam Cullinane joined the French Foreign at age 18

He was to stay with “the Legion” for seven years as an elite soldier, as a mountaineer and a paratrooper with the Special Forces skydiving section. During his career, he saw overseas service in African countries such as Djibouti, Chad, Republic of Central Africa (RCA), Rwanda and Senegal, as well as French Guiana in South America.

Upon leaving it, he wanted to continue outdoor pursuits. In his last year in the Legion, he had read mountaineer Peter Habeler’s book Everest: Impossible Victory, about his and Reinhold Messner’s first ascent of the world’s highest mountain without oxygen. It inspired him to go to the Himalayas for a few months.

On his way back to Europe, the plane happened to stop off, by chance, in Cairo. Cullinane had done some scuba diving while stationed in Djibouti and went to the Sinai and the Red Sea where he stayed for weeks on end to gain his licences. That’s what led to the commercial diving course.

When Cullinane woke to the new reality of his life, it was initially all about survival. Harry had tried to use humour when spelling out what the condition meant. Liam recalls: “It was horrible news to give but inadvertently he made it sound like a challenge I had to overcome.

“If it wasn’t for Harry, I would have had a really tough time. But Harry was my link between the hospital and its world and the outside world. Harry was in his final year in Edinburgh doing accountancy and he failed because he was spending so much time with me.”

The initial treatment was in Glasgow and Edinburgh where doctors told Harry Liam would never get better. Eventually, he returned to Ireland, first to the National Rehabilitation Hospital in Dublin and then to Merlin Park in Galway.

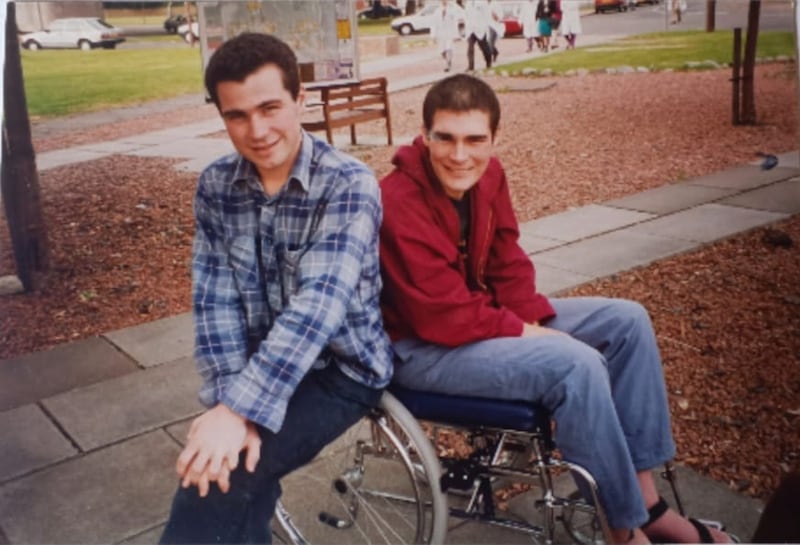

Harry and Liam in outside the Glasgow hospital where Liam was cared for, a few months after he became ill in 1993

Harry and Liam in outside the Glasgow hospital where Liam was cared for, a few months after he became ill in 1993

It was all about small, incremental battles. Initially he could not move, but managed to breathe independently and get into a wheelchair.

He remembers vividly the first time he stood up. He gripped the end of the bed and let go. For an infinitesimal moment, maybe a 10th of a second, he stood unaided.

“After only recently being told I was never going to get up it was amazing. I rang Harry and gave him the news.”

By June 1994, 12 months after he first became ill, he was walking with a frame.

Ever since then, Cullinane’s life has been about healing. Conventional medicine saved his bacon, he has said, but he has availed of perhaps 100 alternative and pioneering treatments and disciplines over the years, ranging from t’ai chi to “brainport” technology, to help with balance, to hyperbaric oxygen. Along the way he has also done a degree in French and philosophy. He’s also gone on a trek to the North Pole with a former classmate, endurance athlete Richard Donovan.

Nowadays he walks without the aid of a cane but balance is still an issue. “It’s a bit like walking along a plank. As long as the plank is straight, no problem. If I need to change direction I need time. So if there are people coming against me I will stop and let them pass and then go on my way.”

His voice is still affected by his condition but the Scottish burr is still there, as is his French accent.

“It’s like building a wall, yeah. You need to put in the bricks but they might not fit perfectly. So sometimes you have to go back a few steps in the process.”

Liam Cullinane in Galway city. Photograph: Joe O’Shaughnessy

There are some hiccups. His accommodation of 22 years is no longer suitable because of damp and he must wait until Galway City Council finds an alternative.

He has one of the calmest demeanours of anyone I know. Does he get frustrated at all with the limitations? His answer is telling. “It’s funny, the closer I get to normal mobility the more I get, not frustrated, but the effort to contain that frustration is getting higher and higher.”

Beyond his own family, he had support from a wide circle of friends, including loyal friends from school. He leavens everything with humour. “The best way to connect with a disabled person is to slag them,” he says.

[ I see in real time the perceptions of people change when they realise I am blindOpens in new window ]

He brings up Tom McEvoy, who designed the zippy tricycle he uses (a familiar sight around Galway city). Cullinane was cycling on Flood Street one day when he heard a cyclist coming behind him who shouted: “Get that piece of s**t off the road.” When he turned around to look at his new adversary, it was McEvoy, whose three-wheelers have been vital on Cullinane’s journey to independence.

Generally he is content. Sipping green tea outside a city centre cafe, he says his first step to recovery was taking total responsibility for where he was and having complete belief in his recovery. He remains forward looking. His long-term goal is to walk the Camino de Santiago with friends.

There is no self-pity, no regrets. Just grace. When I ask him to describe his life now compared to what it was, his response moves me to tears.

“I lived one life until I was 26 years and then life changed. Basically, that life was over, and I was given a second chance.

“Looked at from the external viewpoint, it looks like my second life is nowhere near as good. But it is. I’m actually a much bigger person than I was before. I continue to get bigger and become more and more aware.”