The universe has a habit of throwing curveballs. Just when astronomers think they have the big picture sorted out, something odd pops up in the data and refuses to fit the usual labels.

That is exactly what happened while researchers were quietly sifting through images taken by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

Hidden in wide, deep views of distant space, a handful of tiny objects stood out. They looked like pinpoints of light. That alone was not strange.

What made them hard to ignore was what they were not. The objects did not behave like stars. They did not act like quasars. And they did not line up with any known category of galaxy.

The objects lived very early in cosmic history, when the universe was still young and busy figuring itself out.

Their strange mix of traits has left scientists asking a complicated question that sounds simple: what does a galaxy look like at the very beginning?

Galaxies that can’t be categorized

A team of astronomers at the University of Missouri led by Haojing Yan came across these odd sources while combing through archived Webb data from large extragalactic surveys.

“It seems that we’ve identified a population of galaxies that we can’t categorize, they are so odd,” said Yan.

“On the one hand they are extremely tiny and compact, like a point source, yet we do not see the characteristics of a quasar, an active supermassive black hole, which is what most distant point sources are.”

“I looked at these characteristics and thought, this is like looking at a platypus. You think that these things should not exist together, but there it is right in front of you, and it’s undeniable.”

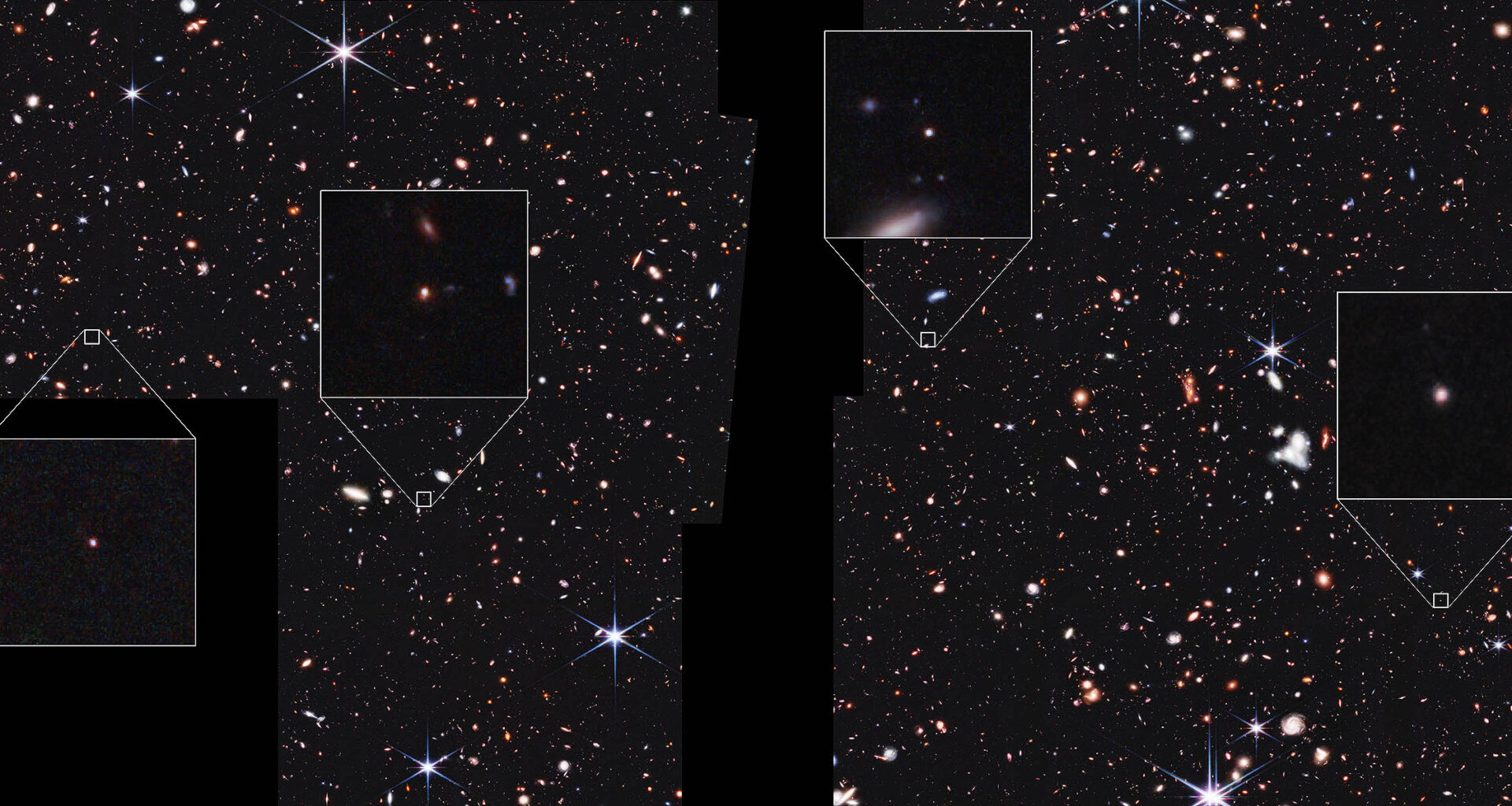

Four of the nine galaxies in the newly identified “platypus” sample were discovered in NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey (CEERS). One key feature that makes them distinct is their point-like appearance, even to a telescope that can capture as much detail as Webb. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, UT Austin. Click image to enlarge.Features of platypus galaxies

Four of the nine galaxies in the newly identified “platypus” sample were discovered in NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey (CEERS). One key feature that makes them distinct is their point-like appearance, even to a telescope that can capture as much detail as Webb. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, UT Austin. Click image to enlarge.Features of platypus galaxies

The discovery did not come from a targeted hunt. The team started with about 2,000 distant sources spread across several Webb surveys.

After careful filtering, only nine objects remained. These nine existed between 12 and 12.6 billion years ago, not long after the universe itself formed roughly 13.8 billion years ago.

Images alone could not explain what they were. So the researchers turned to spectral data, which breaks light into its component colors and reveals physical details that pictures cannot.

These spectra ruled out nearby stars in our own galaxy. They also ruled out quasars, which are usually so bright that they drown out the galaxies that host them.

The signals looked somewhat like “green pea” galaxies found in 2009, but these new objects were far smaller and far more compact.

“Like spectra, the detailed genetic code of a platypus provides additional information that shows just how unusual the animal is, sharing genetic features with birds, reptiles, and mammals,” said Yan.

“Together, Webb’s imaging and spectra are telling us that these galaxies have an unexpected combination of features.”

Reading galaxies through light

One of the clearest clues came from the shape of the spectral emission lines. In typical quasars, these lines are wide – a sign that gas is racing around a supermassive black hole at extreme speeds.

Yan noticed something very different here. The lines were narrow and sharply defined, pointing to much slower gas motion.

There are known galaxies with narrow emission lines and active black holes. But those galaxies do not look like point sources. That mismatch raised an obvious question about whether something entirely different was being seen.

Graduate student Bangzheng Sun took a closer look at whether the signals could come from star-forming galaxies instead.

“From the low-resolution spectra we have, we can’t rule out the possibility that these nine objects are star-forming galaxies. That data fits,” said Sun.

“The strange thing in that case is that the galaxies are so tiny and compact, even though Webb has the resolving power to show us a lot of detail at this distance.”

Lessons from platypus galaxies

One idea gaining traction is that the James Webb Space Telescope is doing exactly what it was designed to do: show astronomers earlier stages of galaxy formation than ever before.

Most researchers agree that large galaxies, including the Milky Way, grew through repeated mergers of smaller systems over billions of years. That story leaves an open question about what comes before even the smallest known galaxies.

“I think this new research is presenting us with the question, how does the process of galaxy formation first begin? Can such small, building-block galaxies be formed in a quiet way, before chaotic mergers begin, as their point-like appearance suggests?” Yan said.

For now, nine objects are not enough to rewrite the textbooks. The team says a much larger sample and sharper spectral data are needed to pin down what these sources truly are and how common they might be in the early universe.

“We cast a wide net, and we found a few examples of something incredible. These nine objects weren’t the focus; they were just in the background of broad Webb surveys,” said Yan.

“Now it’s time to think about the implications of that, and how we can use Webb’s capabilities to learn more.”

The findings were presented at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Phoenix.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–