On a table at Trudy Davis’s home in Kibbutz Lavi stands an Ishka (uisce) branded bottle. An Irish tour group left it behind when they visited the Orthodox kibbutz in northern Israel several years ago.

Davis says tourists visiting Kibbutz Lavi normally struggle to pinpoint the Irish-Israeli woman’s Dublin accent.

Her grandfather, Esomer Davidovich, never intended to move to Ireland when he finished serving with the Imperial Russian Army in eastern Europe in the 1900s.

“The ship’s master told him Cork was New York so he could double his money by taking on more paying families,” she says.

A bottle of Ishka-branded water, left behind by Irish visitors. Photograph: Hannah McCarthy

A bottle of Ishka-branded water, left behind by Irish visitors. Photograph: Hannah McCarthy

After disembarking in Cork in 1903, Davidovich found a Yiddish-speaking Jewish family who explained to him he was not in the United States, but Ireland.

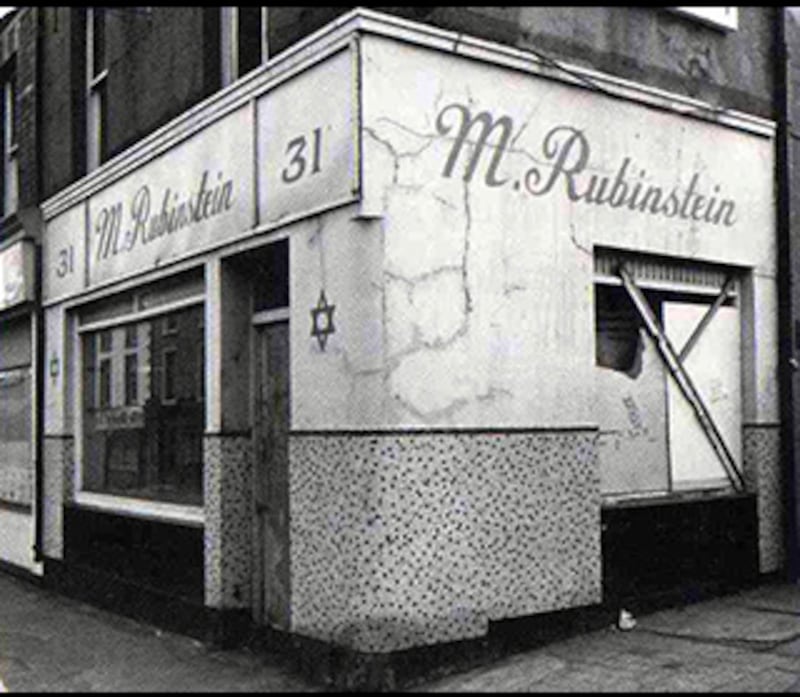

Davidovich, who soon became Davis, moved to Dublin where he worked at Maer Rubinstein and Sons on Clanbrassil Street, a Kosher butcher started by Davis’s maternal great-grandfather.

The South Circular Road was then home to a lively Jewish community and Davidovich’s wife and two children joined him in Dublin. He went on to have more children in Ireland – including Davis’s father, who took over the family butchers.

Born in 1950, Davis grew up in Terenure and received a Jewish education at Zion School on Lombard Street and then Stratford College in Rathgar.

“There were 12 of us in my class, which was the most they had ever had,” she says.

Maer Rubinstein & Sons on Clanbrassil Street in Dublin, a Kosher butcher started by Davis’s maternal great-grandfather. Photograph courtesy of the Irish Jewish Museum

Maer Rubinstein & Sons on Clanbrassil Street in Dublin, a Kosher butcher started by Davis’s maternal great-grandfather. Photograph courtesy of the Irish Jewish Museum

Davis says anti-Semitism was not a feature of her childhood in Dublin, apart from during one hospital stay when a boy in her ward accused Davis of being responsible for Jesus’s death.

“Another boy in the ward told him to shut up and that I wasn’t even born then,” she says.

After leaving school at 16 Davis worked at the Arnotts department store, which later transferred her to a factory office that could better accommodate Davis’s observance of Sabbath, when religious Jews typically do not work.

As she approached 18 Davis moved to Manchester, where her grandparents lived, to be among a more religious Jewish community. “There were very few religious [Jewish] people in Dublin.”

In 1969, Davis was part of a group of youths invited by a religious Zionist organisation called Bnei Akiva to live on an Orthodox kibbutz in the then two-decade-old Israeli state.

Davis spent a year in Kibbutz Lavi, along with two young Jewish women from Cork and Belfast. The Cork woman’s parents had encouraged her to take part in the programme to discourage her relationship with a non-Jewish boyfriend at home.

During her time at Kibbutz Lavi, Trudy Davis met her future husband, Arieh Reisz. Photograph: Hannah McCarthy

During her time at Kibbutz Lavi, Trudy Davis met her future husband, Arieh Reisz. Photograph: Hannah McCarthy

“But after two years, she went back to Cork and she got married to him,” Davis says.

Already living in Kibbutz Lavi, set up in 1949, was the late CB Kaye, who moved from Dublin to Israel in the early 1950s after seeing the condition of young Jews who survived Nazi Europe following their arrival in a refugee camp.

During her year at Kibbutz Lavi, Davis met her future husband Arieh Reisz. When Davis returned to Manchester in 1970 and Reisz was deployed with the Israel Defense Forces Defense Forces to the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt, the two continued to write letters to each other.

Reisz spent much of his military leave in southern Israel’s Kibbutz Alumim, whose members tried to persuade the couple to join the kibbutz.

“We would have had all that trouble as they were invaded by Hamas,” says Davis of the Palestinian militant group’s attack of October 7th, 2023.

Instead, the couple returned to Kibbutz Lavi where they raised four children together. One son still lives in the kibbutz and another lives in Haifa; while one daughter moved out of Kibbutz Lavi but lives nearby and another lives in an Israeli settlement called Pezael, which lies in the centre of the Jordan Valley in the occupied West Bank.

On the debate over the de-naming of Herzog Park in Rathgar next to her former school in south Dublin, Davis says that, as the Belfast-born former Israeli president Chaim Herzog was “given the honour, it certainly should not be taken away”.

“He didn’t do anything that wasn’t honourable,” she says.