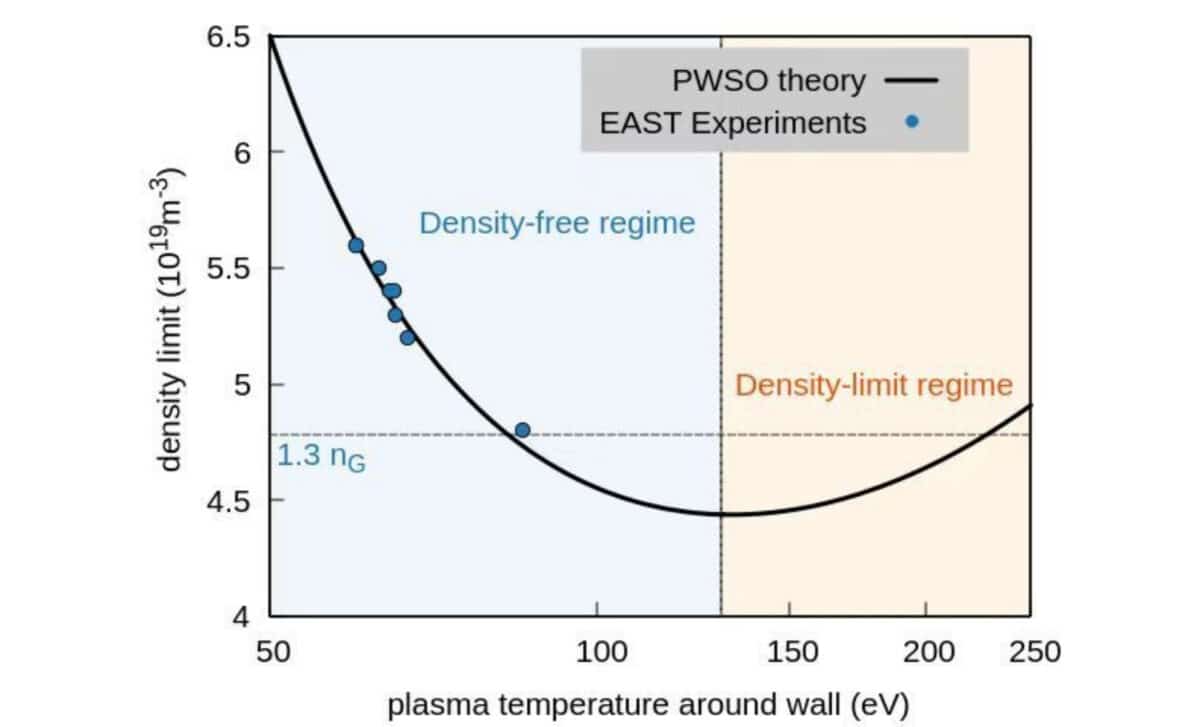

For the first time, researchers have successfully exceeded the Greenwald limit, a critical barrier in plasma density, without triggering instabilities. The experiment achieved a plasma density between 1.3 and 1.65 times the traditional limit without triggering instabilities, marking a significant advancement in controlled fusion technology.

The result is being recognized as a turning point in fusion energy research. Until now, surpassing the Greenwald limit, a barrier tied to plasma instability, remained a theoretical possibility. Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (EAST) has now demonstrated that carefully adjusted conditions can push past this threshold in a working fusion environment. This adds to a growing list of records set by the facility, which previously sustained ultra-hot plasma for over 17 minutes at temperatures above 100 million degrees Celsius.

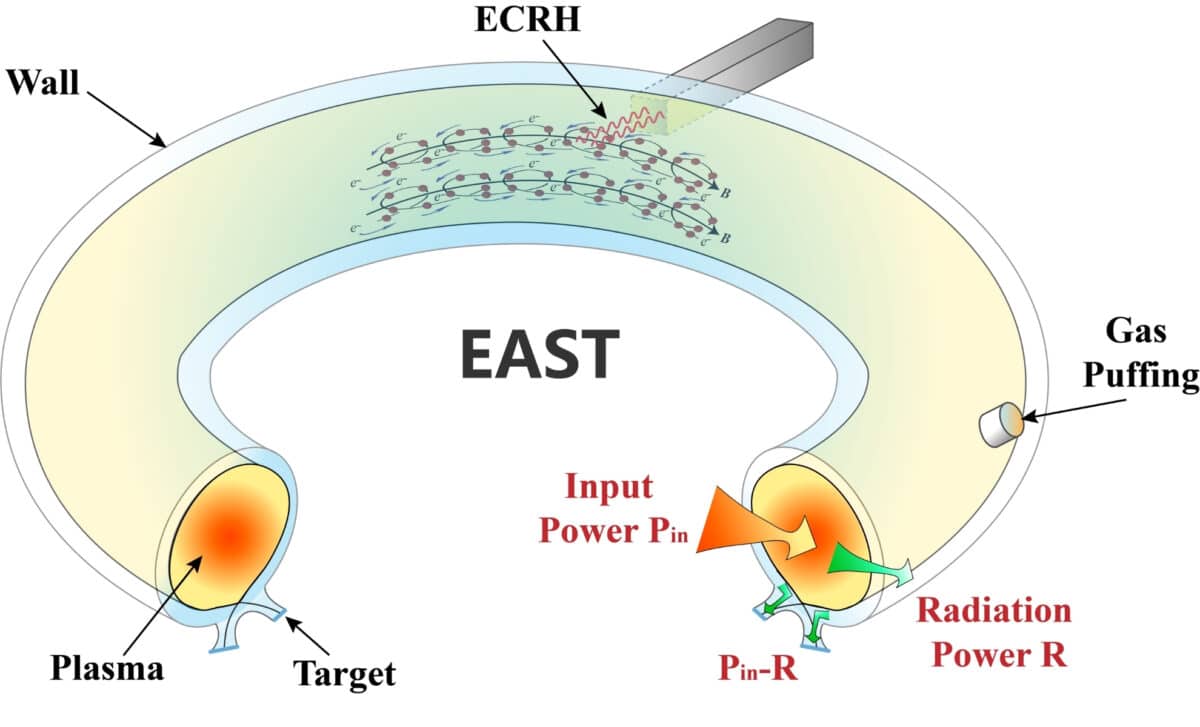

EAST, one of the most advanced tokamak reactors, is designed to replicate the energy process of the Sun, where hydrogen atoms fuse into helium under extreme heat and pressure, releasing energy. In reactors on Earth, it’s not possible to recreate the Sun’s internal pressure, so the plasma must be heated to temperatures roughly ten times higher. Maintaining high density in this plasma is essential for boosting the fusion rate, but until now, doing so above the Greenwald limit posed serious risks.

Record Density Achieved in a Fusion Environment

The Greenwald limit, an empirical threshold used in tokamak designs, represents the maximum density at which plasma can be maintained before becoming unstable. Most operating tokamaks limit plasma density to somewhere between 0.8 and 1 times the Greenwald value to avoid disruptions. While theoretical models have hinted at ways to bypass this limit, they had not been successfully demonstrated in practice under fusion conditions.

EAST researchers achieved this breakthrough by tweaking the initial gas pressure and modifying the heating resonance of the electrons, a technique that changes how plasma particles respond to microwaves. These adjustments allowed the reactor to maintain plasma density beyond the Greenwald limit without the expected instabilities, demonstrating that the limit is not absolute under the right conditions.

According to IFLScience, the findings confirm that “a practical and scalable pathway for extending density limits in tokamaks and next-generation burning plasma fusion devices” is now within reach, quoting Ping Zhu, co-lead author of the study and professor at the University of Science and Technology in China.

Earlier Density Records Lacked Fusion Capability

While EAST’s experiment is a first in a fusion-capable environment, the Greenwald limit had technically been breached before. In past experiments, densities exceeding the limit by more than ten times were recorded, but those involved low-temperature plasma in low magnetic fields, meaning they were not capable of sustaining nuclear fusion. Those earlier attempts offered interesting theoretical insight, but lacked relevance for actual fusion reactor development.

By contrast, EAST’s test involved plasma capable of nuclear fusion, making this the first verified demonstration of Greenwald limit surpassing under real fusion conditions. The EAST team has shown that the previous restrictions on density can be challenged directly with operational changes.

A Growing List of Firsts for East

The EAST reactor has already set a number of high-profile records, establishing its place as a leader in experimental fusion research. One of its most notable achievements was keeping plasma burning for 1,066 seconds, or 17 minutes and 46 seconds, at a temperature exceeding 100 million degrees Celsius, well above the Sun’s core temperature.

This latest success builds on that foundation by showing not just how long and how hot plasma can be maintained, but also how dense it can become in a stable state. The ability to operate a fusion reactor at densities previously considered off-limits strengthens the case for future commercial fusion designs based on tokamak technology.