Northern Ireland is becoming more unequal economically, with Belfast now far outstripping the rest – especially west of the river Bann, a report from the Ulster University Economic Policy Centre says.

Northern Ireland had “significant and persistent regional disparities” in Gross Value Added (GVA) – which measures wages, rent, taxes and profits, minus the cost of inputs, it said.

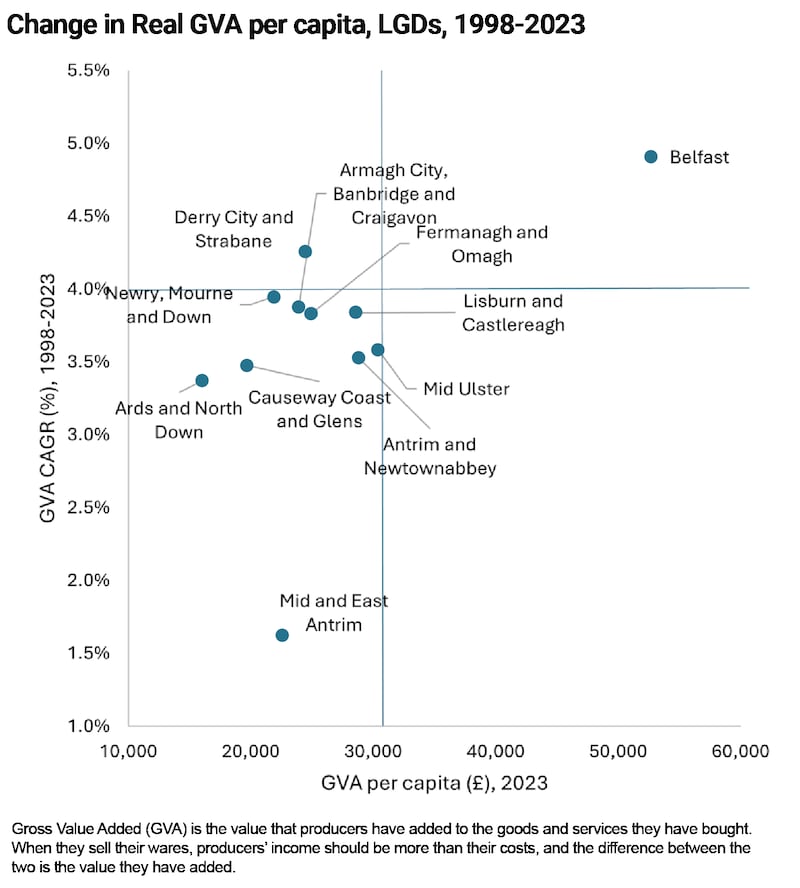

The gap has increased over time. In 1998, Belfast had a GVA that was 42 per cent higher than the Northern Ireland average, but this was now 80 per cent, the study said.

Meanwhile, Stormont’s funding crisis will do little to help the situation, with day-to-day spending in 2026/2027 rising by just 0.8 per cent, and by a further 2 per cent in the following 12 months.

Already, the Department of Health and the Department of Education in Stormont have warned that the budget increases – far below those currently available in the Republic – will pose challenges.

Illustrating the gap, average GVA per capita in Belfast stands at just shy of £55,000 (€63,000) per head per year, while Ards and North Down stands at less than £20,000 annually, with Mid and East Antrim recording less than £25,000.

Employment rates in Northern Ireland’s 11 local authorities “have not altered significantly”, highlighting the challenges facing people living in poorer-off districts to find opportunities “even when employment is growing across the wider economy”.

This is “particularly the case” for districts with “persistently lower employment rates”, such as Derry City and Strabane, but also parts of Belfast – despite the city’s top place overall in the GVA league.

Looking to the future, the Ulster University Economic Policy Centre (UUEPC) warned that long-term growth depended on increased productivity and on targeted policy decisions by Stormont to address regional imbalances.

Contemporary economic policy attempts focuses on a “people in places” approach, which combines regeneration and infrastructure investment with training for workers and grants for businesses.

Two years ago, Stormont’s Department of Economy launched its Economic Vision report to bring about regional balance, which the UUEPC says rightly puts decentralisation at the core of the document.

However, this required “the right leadership and initiatives to tackle core local weaknesses” over many years. “These imbalances have existed for decades, they will not be reversed in a few short years,” the UUEPC said.

The economic study forecasted modest job growth of 0.5 per cent this year before it strengthened over the longer term – but decisions taken now or soon on productivity growth would shape the region’s future growth.

UUEPC director Gareth Hetherington said the figures reflected weak business and consumer confidence combined with geopolitical uncertainty, to which Northern Ireland was not immune.

While 2025 began strongly, contractions occurred later, hitting employment. “Despite this subdued end to 2025, early indications for 2026 suggest progress, albeit modest, with stronger growth anticipated,” he said.

However, the report highlighted how Northern Ireland was becoming a more service-dominated economy, with manufacturing falling back. This has meant workers moving from higher-paid, higher-productivity manufacturing jobs to lower-paid service ones.