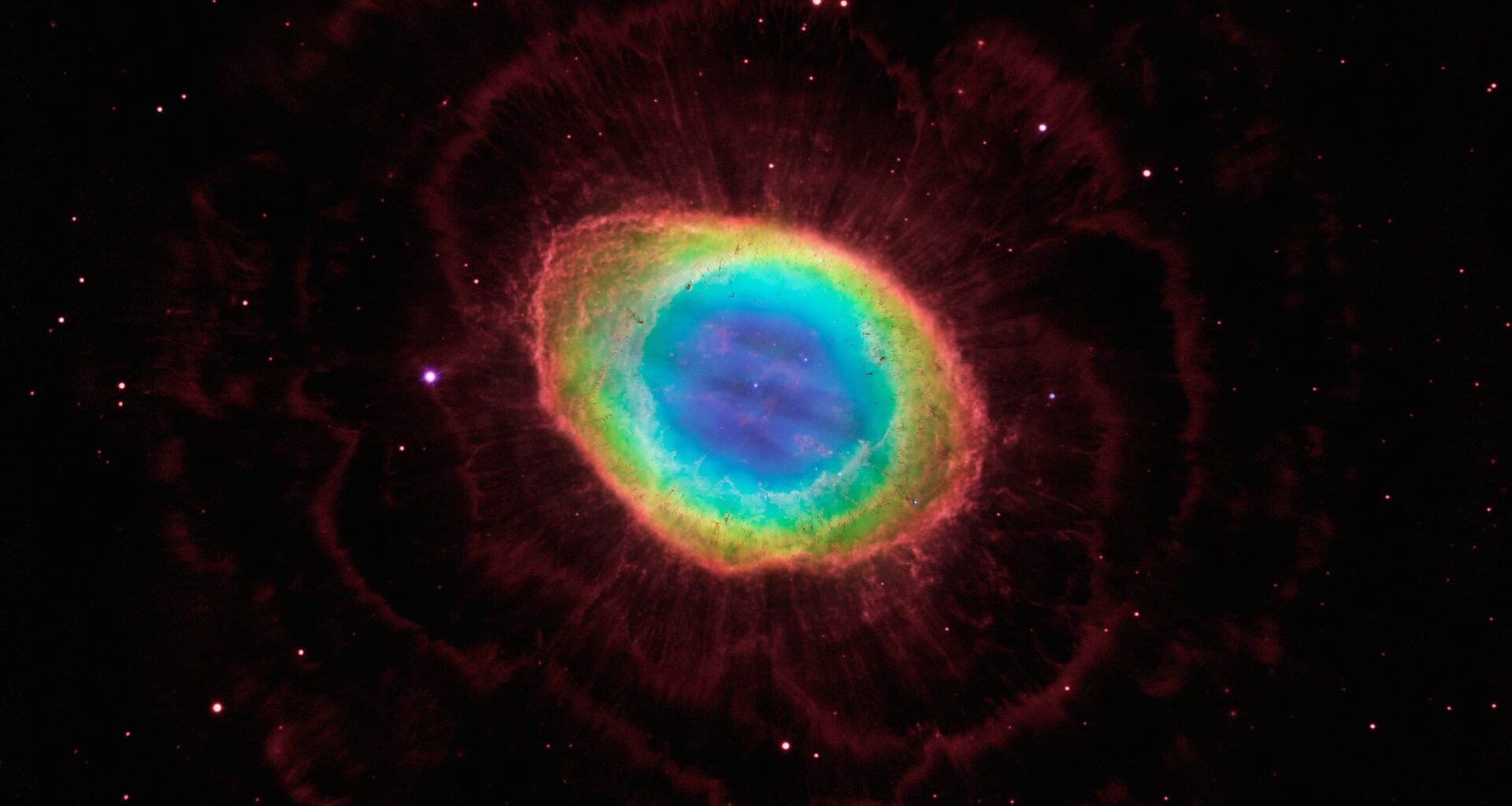

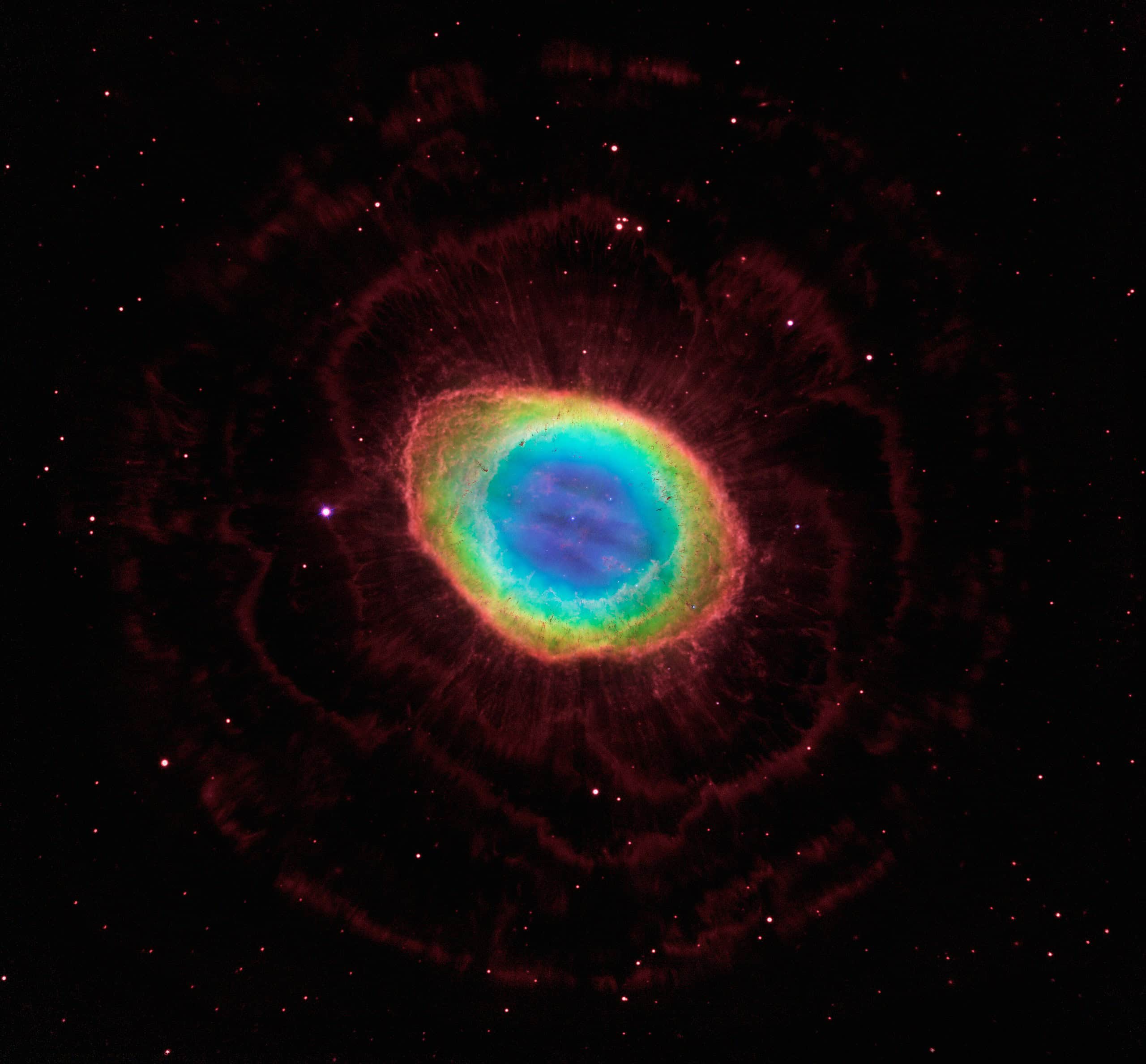

The full shape of the Ring Nebula. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The full shape of the Ring Nebula. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The Ring Nebula is a bright shell of gas in the constellation Lyra. It has long served as a textbook example of how stars similar to the Sun shed their outer layers at the end of their lives. It’s also perhaps one of the most adored nebulae by space enthusiasts, as well as amateur and professional astronomers alike.

Now it has surprised scientists with something wholly unexpected: a massive bar of iron atoms cutting through its center.

The discovery comes from a European team of astronomers using a new instrument on the William Herschel Telescope in Spain. Hidden in plain sight, with an estimated mass comparable to Mars, the iron structure stretches across a region hundreds of times wider than Pluto’s orbit. No one knows how it got there.

“When we processed the data and scrolled through the images, one thing popped out as clear as anything—this previously unknown ‘bar’ of ionized iron atoms, in the middle of the familiar and iconic ring,” said Roger Wesson, an astronomer at Cardiff University and University College London, in a statement.

The findings were published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

A New Perspective

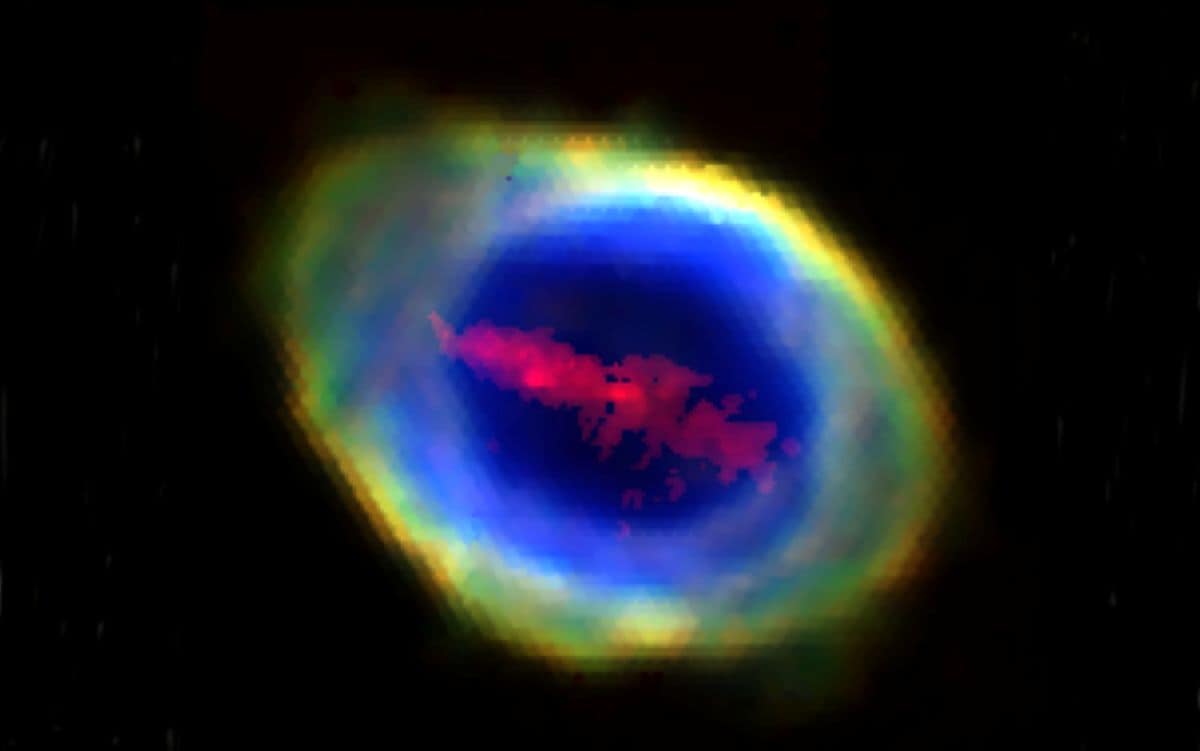

The new chemical map of the nebula, showing the massive iron deposits in the nebula’s “eye”. Credit: UCL/WEAVE

The new chemical map of the nebula, showing the massive iron deposits in the nebula’s “eye”. Credit: UCL/WEAVE

The Ring Nebula, also known as Messier 57, sits about 2,000 light-years from Earth. It is a planetary nebula—a misleading name dating back to the 18th century—formed when a Sun-like star ran out of nuclear fuel and gently shed its outer layers into space. What remains at the center is a white dwarf, the dense core of the former star.

Astronomers have studied the Ring Nebula for decades using many telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope and, more recently, the James Webb Space Telescope. Those observatories revealed intricate shells, knots of gas, and glowing dust. But none of them showed this iron bar.

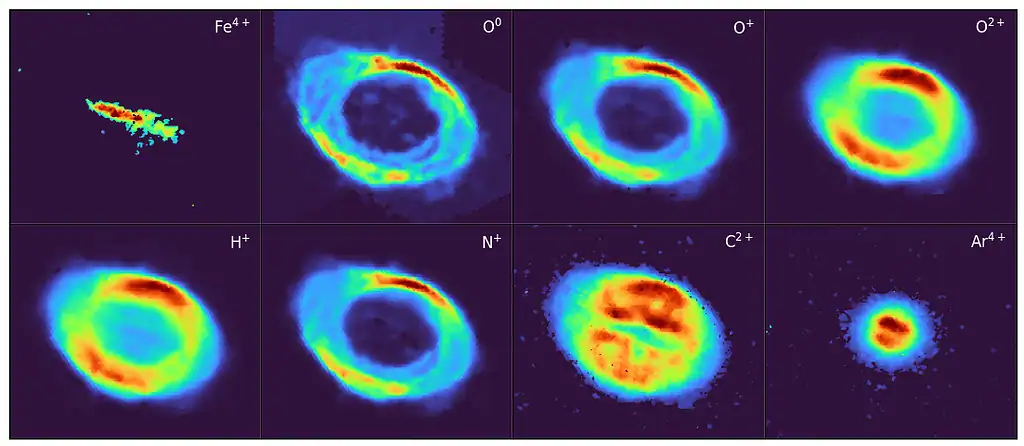

The difference came from a new instrument called WEAVE, short for WHT Enhanced Area Velocity Explorer. Instead of taking a single spectrum from one narrow slice of the nebula, WEAVE can collect light from hundreds of points across the entire object at once. The instrument splits light into colors, letting astronomers map chemical elements across the nebula.

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

That capability turned a familiar object into unfamiliar territory.

The iron appears as a narrow, rod-like cloud running across the nebula’s inner region. It emits light only from highly ionized iron—atoms missing several electrons—while other elements in the nebula do not share the same shape or motion. In the WEAVE data, the iron stands alone.

Its sheer scale makes it hard to ignore. The bar is roughly 500 times longer than Pluto’s distance from the sun, and the total mass of iron detected is comparable to the mass of Mars. For comparison, iron is usually a trace ingredient in nebulae, often locked away inside dust grains.

The Iron Intrigue

Visual split of the nebula’s composition. Credit: UCL/WEAVE

Visual split of the nebula’s composition. Credit: UCL/WEAVE

The presence of so much free iron raises immediate questions. In most planetary nebulae, iron quickly condenses into solid dust as dying stars shed their outer layers, leaving little free iron in the gas. Finding iron atoms glowing freely in space suggests something unusual happened here.

One idea is that the iron bar preserves a record of how the dying star expelled its gas. The star’s ejection could have been uneven, carving out structures that only become visible when viewed with the right tools.

Another explanation points to a process that may have disrupted solid material inside the nebula. Iron usually remains trapped inside tiny dust grains, but damage to those grains could release iron atoms into the surrounding gas. Clues come from infrared images taken by the James Webb Space Telescope, which show that areas rich in iron contain less dust than expected.

What makes this idea puzzling is the lack of an obvious cause. Dust typically breaks apart when it is hit by strong shock waves or exposed to extremely hot gas. Astronomers do not see clear signs of either in the Ring Nebula. The iron is also moving too slowly to have been blasted outward in a narrow jet, leaving its origin unresolved.

“We definitely need to know more—particularly whether any other chemical elements co-exist with the newly-detected iron, as this would probably tell us the right class of model to pursue,” said Janet Drew, an astronomer at University College London and a co-author of the study. “Right now, we are missing this important information.”

The iron bar also does not line up perfectly with the nebula’s central star. Instead, it appears more closely tied to the geometric center of the nebula’s inner cavity.

“It would be very surprising if the iron bar in the Ring is unique,” Wesson added. “So hopefully, as we observe and analyze more nebulae created in the same way, we will discover more examples of this phenomenon, which will help us to understand where the iron comes from.”