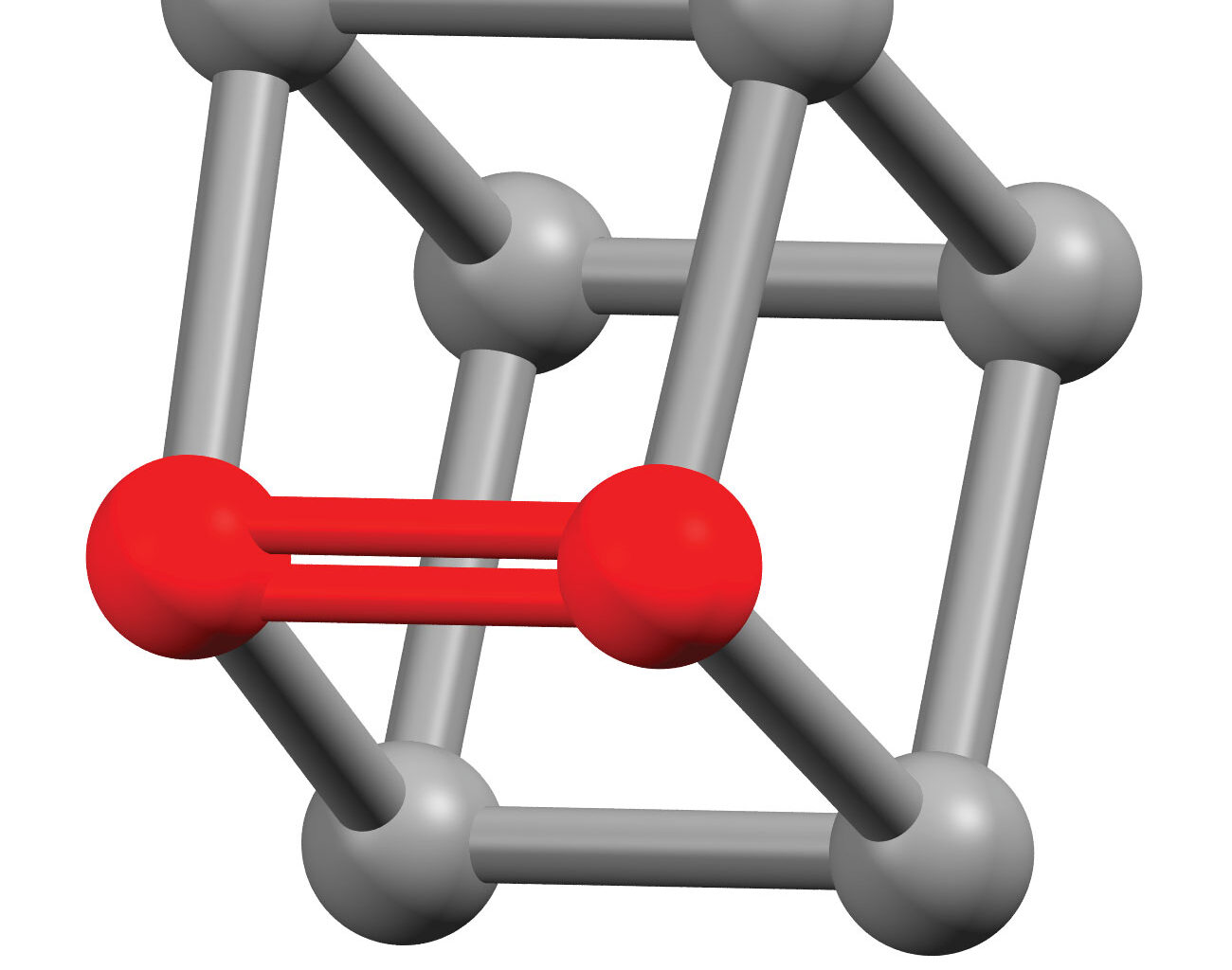

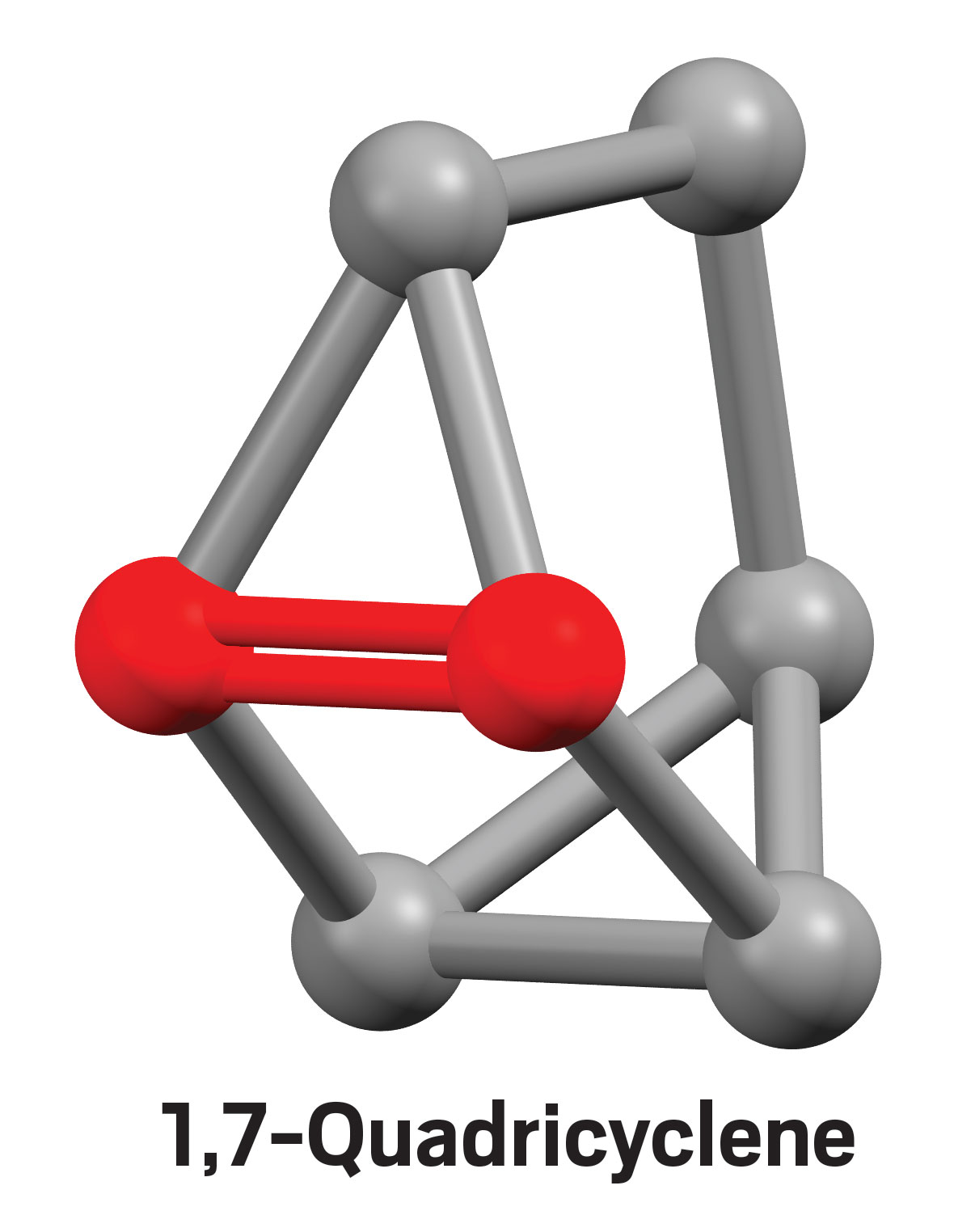

Some people just really enjoy pushing molecules out of their comfort zones. Neil Garg and his team at the University of California, Los Angeles, proudly count themselves among those people. Their latest work, published in in Nature Chemistry, explores the chemistry of cubene and 1,7-quadricyclene, two molecules with extremely distorted double bonds (2026, DOI: 10.1038/s41557-025-02055-9).

It’s “pushing the limits of what geometric distortion looks like,” Garg says.

Cubene and quadricyclene are descended from cubane and quadricylane, both cage-shaped structures with bonds that are fairly distorted from typical alkane geometries, even without a double bond in the mix.

Both alkenes have been made before—quadricyclene debuted in 1979 and cubene in 1988—but nobody really did anything with them, Garg says. “They may have been a little bit ahead of their time.” Nowadays, rigid 3D structures such as cubane are highly desirable in drug discovery, making reactions to install them also desirable. And highly strained molecules are eager to undergo reactions to relieve their stress.

The bonds in cubene and quadricyclene aren’t twisted like the ones in the anti-Bredt olefins that Garg’s team described in an earlier study, but they’re even more bent. Where the bonds to a normal alkene carbon all lie in a flat plane, computational modeling predicts that the bond angles in these molecules are forced out of plane by over 30°.

A 3D rendering of 1,7-quadricyclene, a cage-shaped molecule containing a highly strained double bond.

Credit:

Neil Garg lab

This distortion severely weakens the bond and makes it much more reactive. The double bond in cubene has a bond order of 1.59 and the one in quadricyclene has a bond order of 1.55, well below the normal alkene bond order of 2. The estimated activation energy barrier for a cycloaddition reaction with anthracene is about half as high for cubene as it is for ethylene; the barrier for quadricyclane is even lower.

The molecules are too unstable to isolate, so the team used the same approach they used with the anti-Bredt olefin: generating the alkene from a silyl precursor and then trapping it through a cycloaddition reaction. Based on the products they got, the researchers inferred the fleeting presence of the strained intermediates.

By varying the cycloaddition partners, the researchers constructed a range of funky 3D structures. One of the molecules they made was a dimer they nicknamed “the Beast,” which they formed by linking a cubene trapping product to a quadricylene product.

Paul Wender, an organic and medicinal chemist at Stanford University who was not involved in the work, says that this paper “builds insightfully and innovatively on a foundation of previous and emerging studies” of how unconventional carbon-carbon bonds behave and how to use them in practical chemistry. “There’s lots to unpack, lots to exploit, lots to use.”

Physical organic chemist Alistair Sterling of the University of Texas at Dallas says the work is a great balance between fundamental science and real-world applications. It “really shows that fundamental physical organic chemistry is still alive and kicking, and we still need this type of research to make progress,” he says.

Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright ©

2026 American Chemical Society