Franky Rousell was born deaf. For the first 18 years of her life, her other senses were dialled up. “This lack of a sense fundamentally shaped and heightened — without me even realising — a lot of the perceptions around my other senses,” Rousell says.

Her hearing was “somewhat resolved” after the age of 18, and she “cracked on” with her career in commercial design. But that experience hugely influenced her work, and today she focuses on the idea of sensory design. Rousell defines this as a “subconscious thing that’s happening around you all the time — where all five senses are working really hard to decipher how you’re feeling at any given point of time. Sensory design is about ensuring all those five senses are aligned.”

Franky Rousell set up her sensory-led design practice, Jolie Studio, in 2017

SOPHIA SPRING

A feeling of safety in a space isn’t something that’s consciously decided — rather inferred by body and brain from the cues around you. Perhaps the visuals are trying to calm you, but harsh lighting is doing the opposite.

Have you ever entered a room and instantly thought, “I don’t like it in here”, without being able to pinpoint why? “They can’t put their finger on it, but they feel like there’s something not quite right about the space,” Rousell says. Many interiors can create a misaligned mood. Take a hospital as one example. “From a sensorial perspective, the noises, smells and sounds are very anxiety-inducing, doing the opposite of what that space is trying to do, which is to heal and to care for people.”

Sensory design may sound woo-woo but it is something that can affect our sense of safety and contentment as well as our productivity (and therefore revenues for businesses). The condition sick building syndrome is one manifestation of this, often caused by a series of environmental factors in open-plan offices, such as poor ventilation, bright or flickering lights, and problems with cleaning and layout. “The building … is actually making them really unwell,” Rousell says.

The “inviting” lounge in a two-bedroom flat in Manchester, Rousell’s project for Victoria Magrath

BILLY BOLTON

Looking from the lounge into the kitchen-dining room

BILLY BOLTON

When she set up her sensory-led design practice, Jolie Studio, in 2017, Rousell was working in commercial spaces. “People were spending so much money on design but being trend-driven and surface level, not really understanding the impact of their choices,” she says. “There wasn’t really a practice out there that was able to explain why they should spend £50,000 on a space, other than it just looked cool. I went on a mission trying to make more tangible sense of all this.”

Now sensory design is top of the interiors agenda. At Milan Design Week 2025 multisensory installations were everywhere, from Transposition, a Samuel Ross-designed immersive waterfall (a combination of copper, oak and flowing water) for the whiskey brand The Balvenie, to Aesop’s fragrant, tactile The Second Skin, billed as “an exploration of dermis and design”.

Jolie’s projects range from Manchester’s 60 Fountain Street (a stylish co-working space) and Victoria Riverside, a 634-home development, to safari-style lodges at Chester Zoo, and Hyll, a Cotswolds hotel in a restored 17th-century manor.

• 18 fabulous flatweave rugs to buy now

Begin with a feeling

Most people planning to redecorate start with a set of images as inspiration, perhaps a moodboard on Pinterest. However, when Rousell sits down with a client her first questions are: how do you want to feel in the space? Why do you want to feel that way? What is it that’s lacking?

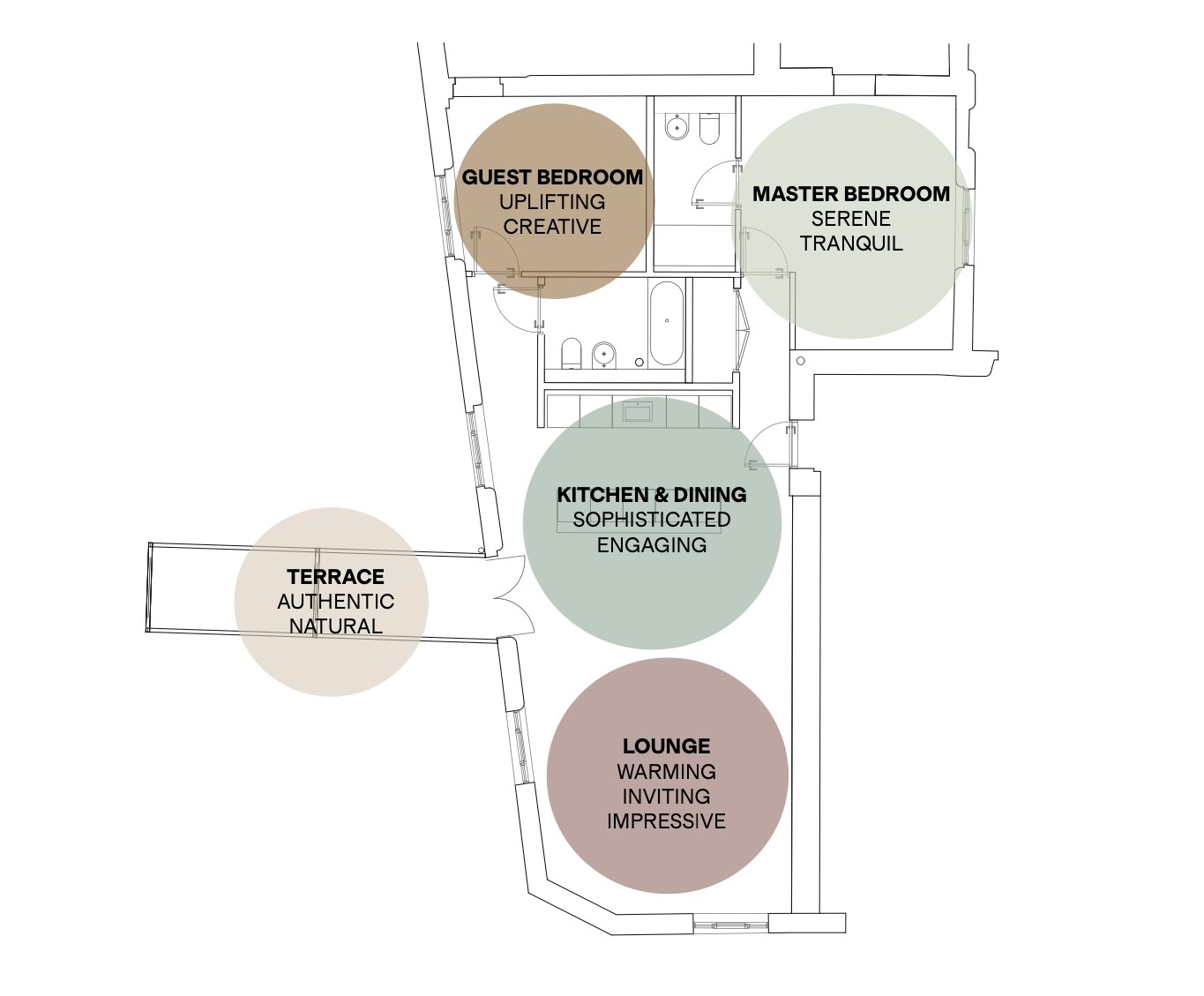

“It’s a little bit like a therapy session,” she says. “We really dig deep.” From those conversations, the Jolie team creates a labelled floor plan broken down into bubbles naming the desired emotional output. This is called “sensory zoning”.

Using a host of science-led information — “Everyone from touch neuroscientists to gastro-physicians” — they translate the goals into a physical plan: this colour, paired with these materials, and this fragrance and soundscape.

Left: cold, hard surfaces encourage movement in an entrance hall at Victoria Riverside, Manchester. Right: a cosy reception area at The Reserve, a safari-style retreat at Chester Zoo, has been designed for lean-in conversations

Jolie Studio will often then stage an experience for the client, for example immersing them in computer-generated imagery, fragrancing the room, creating a bespoke soundtrack, while explaining the intent. When senses align, people feel it immediately — some have been “reduced to tears”.

Rousell adds: “Softer, warmer textures are great for opening up more meaningful conversations in lounge settings. You shouldn’t go for cold, hard marbles because that will close off conversation and create aversion, but those harder textures can be useful in settings where you do want people to move through quickly.

“Some strong, saturated colours can promote anxiety, so it’s all about careful consideration and balance, so as not to be boring.” She advises being cautious with the trend for “drenching” a room in a single colour. “The colour orange has been proven to change somebody’s behaviour as much as fragrance.”

• Andrew Buchanan: My ‘Folkey’ (renovation) tale

Be consistent with colour

In a previous Jolie project, decorating a two-bedroom apartment in Manchester for Victoria Magrath, a lifestyle content creator, that had an open-plan kitchen, living and dining room, “balance” was the overriding feeling the final design was aiming to achieve.

The desired mood bubbles on the floor plan were “sophisticated and engaging” in the kitchen/diner and “warming and inviting” in the lounge area. The paint palette included fresh greens (Acorn by Little Greene) and chalky neutrals (Duvet Day, a sandy beige, from Coat) with accents of deep green and burgundy. “Serene and tranquil” was the vibe in the principal bedroom — again using greens (this time a paler grey-green shade by Coat called Yard Party) plus chalky neutrals and another touch of deep burgundy.

A floor plan mood board for the aforementioned two-bedroom apartment that Jolie Studio designed

A mood board for the kitchen-dining room

It’s all about balance and cohesion. The goal is not to create different personalities in the spaces —rather, Rousell compares the design approach to music: bass notes (consistent palette), rhythm (repeated cues) and top notes (dashes of personality) that change room by room.

“You can play a lot more in a hotel, but when it comes to home design it’s important to create a palette that speaks to every single room in your home — it’s a space that you’re going to be spending a lot of time in for a number of years,” she says. “You’re trying to do quite a lot within a small area.”

Curate a peaceful soundscape

“Our ears are the only things that never switch off,” Rousell says. Anyone who’s lived in a flat beneath a stomping neighbour or heard next door’s relentless arguments through the Victorian terrace walls will understand this viscerally. It’s not just annoying but can put you on high alert as you wait for the next clunk or bang.

“Sound is tied into our fight-or-flight response,” she says. “Allowing people to retreat to restful spaces is so important, especially in our big cities where adrenaline and cortisol are probably at their highest. Birdsong, for example, is proven to release serotonin. If the birds are singing, then we know that everything’s fine.”

At build stage, audio considerations include adding insulation in walls, ceilings and cavities, “boosting airborne and impact sound reduction”. Rousell uses Noisestop for internal linings and Hush Acoustics for sound-insulating ceiling systems. “In older buildings, acoustic-backed plasterboard internally is a common retrofit solution that avoids disturbing external façades,” she says.

Less intrusive adjustments include sound absorption via rugs, cushions, specialist fabrics (Delius) and acoustic curtains (Création Baumann) and so on, to reduce reverberation and airborne noise. “[Use] ceiling treatments, padded panels, or wall-mounted art to spread out localised noise impacts like footsteps or door slams,” Rousell adds. Furniture, bookshelves, artwork or plants can all help to diffuse sound, especially if you can’t make more permanent changes to an interior scheme.

Franky Rousell’s five sensory design tips1. No visual clutter

Don’t overstimulate the nervous system with clutter. Choose functional storage solutions with a homely aesthetic, such as vintage dark-wood sideboards or low-level units. Soft storage baskets on open shelving can discreetly house books, tech and daily essentials within reach. These are best to sit at a lower level, with decorative items displayed at eye level.

2. Don’t rely on overhead lighting alone

Lighting shapes how we feel in a space more than almost anything else. Harsh overhead light flattens depth and can feel interrogative. Instead, layer light sources: soft pools from table lamps, wall lights at eye level, dimmers that echo the shifts of natural daylight.

Rousell says texture is an important element of sensory design

SOPHIA SPRING

3. Consider texture

When surfaces are overly smooth or polished, our senses disengage. Surfaces that are cold and hard encourage movement, meaning people are less inclined to linger. They are best avoided in rooms where you want relaxation and stillness. Warmer, softer textures draw people in and can foster open, meaningful conversations, though they may not be ideal in areas subject to heavy use or wear. Natural materials such as woods, clays and stones bring a grounding quality.

4. Respect the day’s natural rhythms

Heavy curtains drawn all day or sealed-off rooms disrupt the body’s connection to time. Let daylight in where you can and encourage cross-ventilation. Arrange furniture to guide circulation and avoid blocking sightlines to windows. Even small changes, such as lowering a pendant lamp to draw you into a dining space, can create a sense of rhythm.

5. Pick the right scent

Fragrance is a quiet but powerful layer of design, capable of sparking memory, grounding us in the moment and subtly shifting mood. It’s the difference between a space that looks good and one that feels like home. Choose scents that align with the rhythm of the day: herbal or citrus in the morning for clarity, resinous or amber notes in the evening for calm.